The Three Sea Hawks

The Navy’s First Aerobatics Team, 1928–29

Curtiss flying boat over a ship in U.S. waters, c. 1918. (Naval Heritage and History Command [NHHC], NH 60770)

The Golden Age of Aviation

Following the November 1918 armistice that ended World War I, the U.S. presidential administration immediately began issuing orders to lift wartime bans on civilian flying and allowed for a resurgence of aviation as a form of public entertainment. This started an upsurge in excitement over airplanes and flying, and the 20-year interwar period became known as the “Golden Age of Aviation.” Civilian aviation enthusiasts benefitted from military surplus aircraft produced to train pilots during the war and the return from overseas of the military aviators themselves. Air races and barnstorming, a style of flying in which pilots performed tricks in an airplane either individually or in group formations, became increasingly popular.[1]

The U.S. Army Air Service immediately saw the potential in this type of public presentation, even creating its own flying circus, the Victory Loan Flying Circus, to encourage the purchase of war bonds as part of an effort to pay off the nation’s debt after the war.[2] This form of flying sparked debate over the value of aerobatics, in both civil and military aviation magazines. One writer commented that “from the military standpoint every form of stunting is helpful as it not only tests the capabilities of the machines but demonstrates the skill of pilots.”[3] Concern grew among early businessmen in the airline industry that stunt flying would discourage the public from thinking of the airplane as a form of travel for passengers. Aerobatics made flying look too dangerous for the average person. Also, as the crowds expected more with each performance, the stunts became increasingly dangerous, which led to an increased number of fatalities associated with aviation industry. As early as 1926, the federal government began passing laws to regulate civil aviation and to prohibit low-altitude stunts. That did not stop military aviators from testing the limits of their aircraft under the guise of training. Stunt flying offered ambitious aviators the opportunity to push themselves and their aircraft to physical limits.

The Three Sea Hawks Team Leader

Lieutenant Daniel W. Tomlinson, IV, graduated from the Naval Academy two months early when the United States entered World War I in 1917, but did not earn his wings until 1921. He craved innovation and competition, and he occasionally got into trouble. He was court-martialed once in 1922 for colliding with another aircraft while attempting to join a formation.[4] Although he was acquitted, he was temporarily grounded because he was believed to be “too dangerous.”

It was during this time that he bought his own Curtis JN-4 “Jenny” from military surplus. While flying his plane in Southern California, he met Earl Daugherty, the owner of an airfield and a flight school near Long Beach.[5] Daugherty was a pioneering aviator and a barnstormer. His school became Tomlinson’s training ground for learning aerobatics. Following a year aboard USS Oklahoma (Battleship No. 37), Tomlinson was ordered to the East Coast in 1923 on assignment to the Naval Academy. There, he served as an instructor in the marine engineering department until 1925.[6] After this rotation, he was permitted to return to aviation.

In October 1925, Tomlinson received orders assigning him to as a flight officer with Fighting Squadron 6 (VF-6) in San Diego. He later served as the unit’s executive officer and then briefly as its commanding officer. During this time, his squadron was redesignated as VF-2 (January 1927) and then VF-2B (April 1927), the “B” indicating its bombing role. His squadron was originally equipped with Curtiss F6C Hawk. This aircraft was among those used in trial operations aboard the Navy’s first aircraft carrier, Langley (CV-1), beginning in 1926. Tomlinson relished being back in the air and he sought out every opportunity to expand his knowledge of what an airplane could do.

In September 1927, while temporarily detached from his squadron to fly to the Boeing factory in Seattle, Tomlinson requested permission to attend the National Air Races at Spokane, Washington. At this event, he first witnessed the aerobatics of the Army Air Corps’ “Three Musketeers,” led by Lieutenant James “Jimmy” Doolittle. Tomlinson was amazed because Doolittle had modified the carburetors in the Army’s Curtiss PW-8 Hawks (the same airframe as the Navy’s F6C) to allow the aircraft to sustain inverted flight for 45 seconds. This type of engine was built for pursuit, for racing, rather than aerobatics. During inverted flight, the D-12 engine would cut out when the float carburetor is inverted, as the float rises and cuts off the supply of fuel.[7] The float depended on gravity to function properly. Doolittle plugged the fuel line to the carburetor with solder and then drilled a hole through the plug to allow enough fuel to sustain full power without the engine cutting out.[8] When asked, Doolittle explained to Tomlinson how to modify the F6C carburetors in the same fashion.[9] In the same air show, Tomlinson was not impressed with the Navy’s performance and became determined to create his own team for the next races.[10]

Training “on the QT”

Following his experience at the National Races, Tomlinson, at this point the executive officer of VF-6B, returned to San Diego, where he handpicked pilots for his proposed section (each section within a Navy squadron consisted of three pilots). [11]He selected Lieutenant (j.g.) William V. Davis, Jr, and Lieutenant (j.g.) Aaron P. Storrs, III.[12] Once he had the pilots, they began practicing at their North Island station. The Boeing FB-5 then flown by Tomlinson’s squadron was not ideal for what they were doing, but it was better than the Vought VE-7 they had been flying the prior year while carrying out trial flight operations aboard Langley.[13]

A Boeing FB-5 in flight while assigned to VF-6 in San Diego, c. 1927. (San Diego Air and Space Museum, J.M.F. Haase Collection, 00036789)

In January 1928, the squadron was due to receive a new aircraft, the Boeing F2B-1. The first flight of the F2B prototype (XF2B) had taken place on 3 November 1926. Thirty-three of the production models were delivered to the Navy in January 1928, including those allocated to Tomlinson’s squadron based on Langley.[14] This would be the first aircraft flown by the Navy’s first aerial acrobatics team, 18 years before the establishment of the Blue Angels.[15] The F2B’s specifications initially did not permit inverted flight. Tomlinson had to request a modification of the carburetors according to Doolittle’s advice to permit the stunts that he wished to perform.

Three F2B-1 fighter planes in flight, tethered together by lines running from wingtip to wingtip, c. 1930. These may be planes of the "Three Sea Hawks" aerobatic team. (NHHC, NH 94858)

This aerobatic team was not official. Their training sessions were kept quiet, or “on the QT.”[16] Neither Tomlinson nor his wingmen were officially assigned this duty.[17] Initially, they trained over land and above the clouds near San Diego.[18] However, despite attempting to keep their activities quiet, their stunts did attract attention when they did not resist the urge to show off. Tomlinson’s chain of command obviously knew what he was doing within a few months.[19] As soon as they had an opportunity, his leadership put the performance on public display.

(Left to right) Lieutenant (j.g.) William V. Davis, Jr., Lieutenant Daniel W. Tomlinson, IV, and Lieutenant (j.g.) Aaron P. Storrs, III, while assigned to Naval Air Station North Island, San Diego, California, c. 1927–29. (NHHC, NH 120169)

The “Suicide Trio”

In April 1928, Tomlinson’s squadron was aboard Langley headed to San Francisco with 35 planes crowding the flight deck. Tomlinson’s fledgling team joined 26 other aircraft launched from the carrier on 12 April for an aerial show over the city.[20] Tomlinson claimed to have flown inverted over the buildings along Market Street during the demonstration.[21]

Among the stunts demonstrated by his team were the outside and inverted loops, but it is unclear whether these were sanctioned by his leadership. Only specific maneuvers were given prior approval, but there were times during the flyover of the city when naval leaders on the ground could not see the demonstration.

U.S. Navy planes fly over San Francisco's Pacific Telephone building, c. 12 April 1928. (First printed in San Francisco Examiner, 12 April 1928)

Nicknamed the “Suicide Trio” after their first public appearances, it was Storrs who originally came up with the name “Three Seahawks” during the summer of 1928.[22] Despite their name, the trio originally flew F2B-1s assigned to their squadron rather than Curtiss Hawks.

Following the presentation in San Francisco, the carrier departed for a strategic exercise (Fleet Problem VIII) off the coast of Hawaii. During this exercise, the squadrons assigned to Langley were able to launch 35 aircraft in seven minutes.[23] Unlike the aerial show over San Francisco, where Tomlinson’s team had carried their more dangerous stunts out of the Navy leadership’s view, , they put on a complete show for the commanding officer of Langley, Commander John H. Towers. Afterward, Towers addressed Tomlinson directly, saying “‘Tomlinson, I think the Air Corps has been sufficiently impressed.’”[24] It was likely a subtle hint to Tomlinson to stop what he was doing, but Tomlinson took it as a compliment and permission to continue practicing, just not during fleet exercises. Their practice aboard Langley in April 1928 was officially recorded in the ship’s log.[25]

When planning activities for another naval demonstration in San Francisco in May 1928, Commander Eugene E. Wilson, the chief of staff to Rear Admiral Joseph M. Reeves, Commander Aircraft Squadrons, Battle Fleet, asked Tomlinson and his wingmen to “‘put on a show.’”[26] On 17May 1928, they were part of the demonstration line-up.[27]

Shortly after this event, Secretary of the Navy Curtis Wilbur issued a directive prohibiting naval aviators from attempting inverted or outside loops unless expressly permitted.[28] It was unlikely that this statement was directly related to Tomlinson’s own activities since the exception provided a “loophole” for aerial demonstrations by trained aviators such as Tomlinson. Wilbur’s directive may have been urged by the early airline industry, which wished to shift the public perception of aviation safety. Stunts and accidents in the news did not help their efforts, even if the pilots involved were military aviators. Previously, in April 1928, the Secretary of the Navy had responded to this pressure by appointing a board to investigate developing more safety in naval aviation because of the high fatality rate.[29] The demonstrations by Tomlinson’s trio were risky, but Admiral Reeves seemed to understand the value of this team and what they could do at a time when it was politically precarious to support their activities.

F2B-1 fighter plane on the flight deck of Langley (CV-1), c. 1928. (NHHC, NH 71024)

Navy Leadership and the Navy’s First Aerial Stunt Teams

Admiral Reeves permitted another public display in August 1928.[30] Despite the recent limitations placed on Navy planes performing stunts in public exhibitions, there were allowances made for the “dedication of airports and landing fields or features having naval or military significance.”[31]

Secretary of the Navy Wilbur received a preview of the coming event on 14 August 1928 at North Island.[32] He allowed the air show to go forward as planned.

At the dedication of Lindbergh Field on 16 August in San Diego, the U.S. Navy flew approximately 222 planes over the city in a demonstration of aerial strength. The aerobatics of the Three Sea Hawks were only part of the spectacle.[33] They performed a series of loops, rolls, and dives.[34] Reeves provided commentary throughout the whole show, in full support of his naval aviators, including the Sea Hawks.[35]

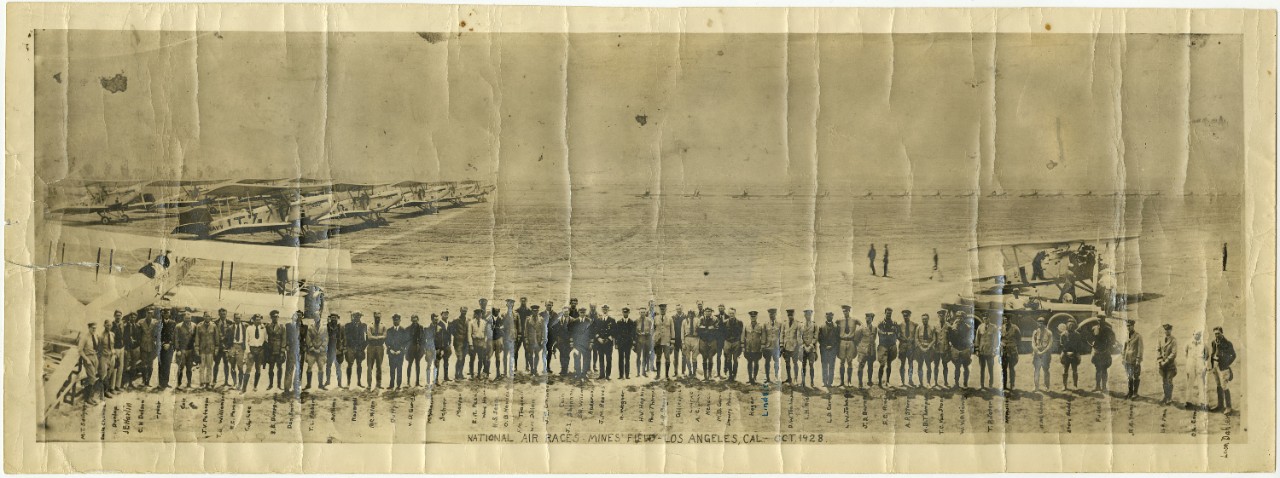

Panoramic group photograph of 65 of the pilots who participated in the 1928 National Air Races at Mines Field, Los Angeles, California, 8–16 September 1928. (Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, 9A08524)

At the National Air Races at Mines Field (Los Angeles) in September 1928, the Three Sea Hawks and the Three Musketeers both performed for the crowds. Unfortunately, Lieutenant John J. Williams, the leader of the Musketeers, was killed when his plane crashed during the Army’s performance. The performance at Mines Field was the last for the Sea Hawks. Williams’ tragedy and others in the field of civil aviation amplified public perception about the dangers of exhibition flying and the need for government regulations to prevent pilots from engaging in “stunt flying.”[36] However, that was not the only reason for the end to the Sea Hawks. Tomlinson wanted to be a test pilot and was vying for a billet at NAS Anacostia, Washington, DC. In the fall of 1928, he received orders to Anacostia as the chief test pilot for the Navy.[37]

Although the Three Sea Hawks had disbanded, their legacy remained alive. The annual report from the commanding officer of the Battle Fleet made specific reference to the presence of VB-2B to the National Air Races as a special operation of the fleet.[38]The annual report of the Secretary of the Navy credited this squadron with bringing “favorable publicity to the Navy as a whole.”[39] In 1929, the trio was featured alongside Langley in a silent film, The Flying Fleet, filmed in the summer of 1928.

The Flying Fleet film advertisement, reprinted in Wisconsin Rapids Daily Tribune, 17 April 1929.

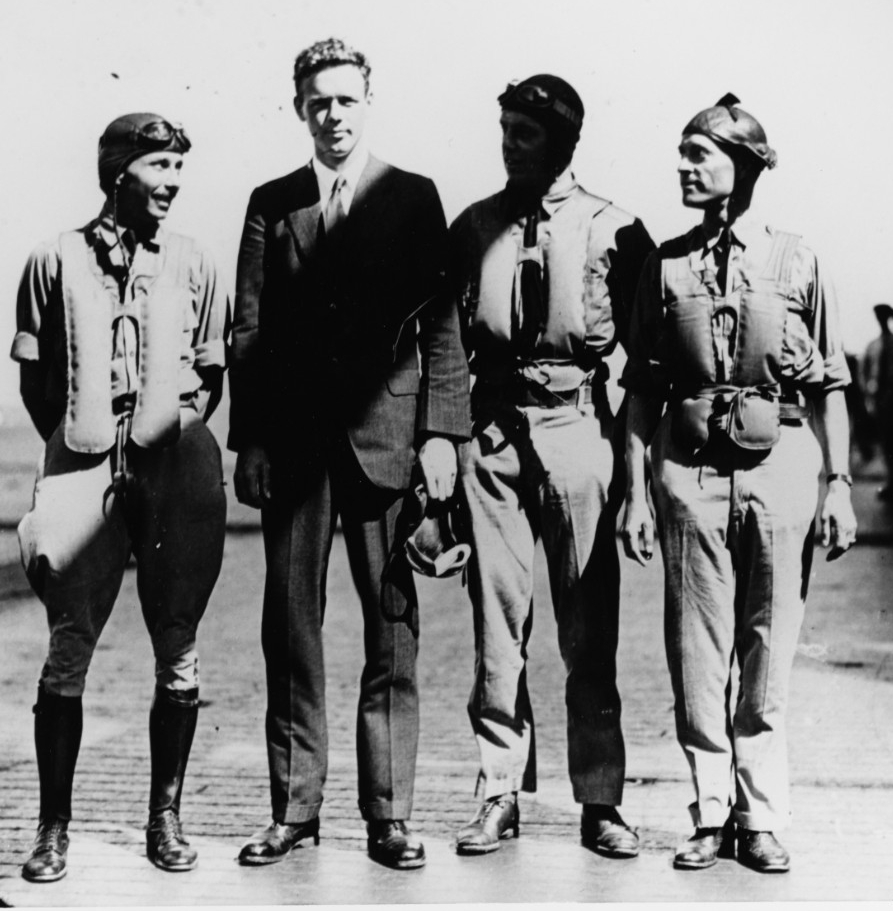

The Sea Hawks were not the only military aerobatic team composed of Navy pilots prior to 1946. VF-1B formed the “High Hatters.” Former “Sea Hawk” Lieutenant Bill Davis flew with the pilots of VF-1B while assigned to Saratoga (CV-3). It was during this time that Davis met Charles A. Lindbergh when he visited the ship in February 1929.

That same year, 1929, Davis joined the “Three T’Gallants’ls,” or “Three Top Gallant Sails,” another aerobatic troupe formed from Training Squadron 5 (VT-5), based in Pensacola.

Charles A. Lindbergh (second from left) on board USS Saratoga with three naval aviators, including Lieutenant Bill Davis (left), c. February 1929. (NHHC, NH 94860)

In 1930, Admiral William A. Moffett created an aerial demonstration team from the flight test section at Anacostia, the “Three Flying Fish.”[40] Lieutenant Matthias B. Gardner was put in charge. Former Sea Hawk Lieutenant Aaron Storrs was assigned to this new unit along with Lieutenant Frederick M. Trapnell. They demonstrated at the National Air Races at Chicago and several other events in 1930 before they were disbanded in 1931.[41]

After World War II, Admiral Chester Nimitz, as the Chief of Naval Operations, formed the Blue Angels, who have been active and very much in the public eye since 24 April 1946. They are fitting descendants of the Three Sea Hawks.

—Kati A. Engel, NHHC Communication and Outreach Division, July 2024

***

NHHC Resources

Hill Goodspeed, The History of Blue Angels Aircraft: A Photo Essay,

Further Reading

Fritze, Marga R. Blue Angels. Osceola, WI: MBI Publishing, 1996.

Tomlinson, Daniel W. The Sky’s the Limit. Philadelphia, PA: Macrae Smith Co., 1930.

———. “Golden Eagles, the Three Seahawks,” Naval Aviation News (April 1979): 36–39.

Tomlinson, Daniel Webb, Barrett Tillman, and Paul Stillwell. The Reminiscences of Captain Daniel Webb Tomlinson IV, U.S. Naval Reserve (Retired). Annapolis, MD: U.S. Naval Institute, 1995.

Wildenberg, Thomas. All the Factors of Victory: Admiral Joseph Reeves and the Origins of Carrier Airpower. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2019.

Notes

[1] This type of flying earned its name from the pilots’ early habits of landing at a local farm to negotiate for a temporary venue for an air show.

[2] Maurer Maurer, Aviation in the U.S. Army, 1919–1939 (Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History, 1987), 28.

[[3] “Are Acrobatics Helpful?” Aircraft Journal, 7 June 1919.

[4] Navy Department, Compilation of Court-Martial Orders, vol. 1, 1916–1937 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office [GPO], 1940), p. 806.

[5] “The Three Seahawks,” Naval Aviation News, April 1979, 36.

[6] Annual Register of the United States Naval Academy, 1923–1924 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1923), 17.

[7] Patricia Trenner, “How Things Work: Flying Upside Down,” Smithsonian Air & Space, May 2002.

[8]Naval Aviation News, April 1979, 36.

[9] Daniel W. Tomlinson, “Interview Number 2 with Captain Daniel W. Tomlinson, IV, U.S. Naval Reserve (Retired),” interview by Barrett Tillman, 10 September 1985, p. 102. Hereafter cited as TOH.

[10] TOH, 103.

[11] This unit was redesignated from VF-6B in January 1927, and then VF-2B following its transfer to Langley, and then to Bombing Squadron 2 (VB-2B) on 1 July 1928. Tomlinson first served as a flight officer, then executive officer, and ultimately the commanding officer of this squadron. See “Lineage for Fighter Squadrons,” Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC) (PDF). Note the B appended to end of the squadron designation indicates attachment to the Battle Fleet rather than the Scouting Fleet. These designations were removed after 1937.

[12] Davis had already earned fame as the navigator of the monoplane flown by famous stunt flyer Arthur Goebel during the August 1927 Dole Race to Hawaii.

[13] Daniel W. Tomlinson, The Sky’s the Limit (Philadelphia: Macrae Smith Co., 1930), 109; William V. David, letter to the editor, Naval Aviation News, January 1959, 36.

[14] VF-1B and VF-2B were both

[15] The Blue Angels team was officially established on 24 April 1946 by order of Chief of Naval Operation Admiral Chester Nimitz.

[16] TOH, 105.

[17]Oakland Post Enquirer, 12 September 1928; Fritze, Marga R., Blue Angels, p. 11.

[18] TOH, 105.

[19] Thomas Wildenberg, All the Factors of Victory: Admiral Joseph Mason Reeves and the Origins of Carrier Airpower (Washington, DC: Brassey’s Inc., 2003), 159.

[20] San Francisco Examiner, 12 April 1928; Clark G. Reynolds, Admiral John H. Towers: The Struggle for Naval Air Supremacy (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1991), 216.

[21] TOH, 106. Note Tomlinson was not the first to officially accomplish this feat. Lieutenant Alford J. Williams was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross on 16 May 1929 for the achievement of inverted flight at Naval Air Station Anacostia in March 1928. See United State Naval Aviation, 1910–1995, 72.

[22]Los Angeles Times, 16 July 1928; Los Angeles Times, 21 August 1928; Tomlinson, 114.

[23] Samuel Cox, H-069-1: "The Covered Wagon”: USS Langley (CV-1), NHHC.

[24] TOH, 109–10.

[25] Reynolds, 217.

[26] TOH, 105. Note that Admiral Reeves commanded all the aviation assets of the Navy’s operating forces.

[27] San Francisco Bulletin, 17 May 1928.

[28] Aviation, 28 May 1928, 1562.

[29] Washington Post, 5 May 1928.

[30] For further reading about Admiral Reeves’s role in early aerial innovation in the U.S. Navy, see Thomas Wildenberg, All the Factors of Victory: Admiral Joseph Reeves and the Origins of Carrier Airpower (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2019).

[31] New York Times, 11 August 1928; reprinted in Evening Journal (Wilmington, DE), 11 August 1928.

[32] Wildenberg, 175.

[33] Aviation, 25 August 1928, 602.

[34] Eugene E. Wilson, Slipstream: The Autobiography of an Air Craftsman (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co., 1950), 134

[35] Wildenberg, 177.

[36] Evening Journal (Wilmington, DE), 27 November 1928.

[37] His friend and mentor, Earl Daughtery, died in a plane crash on 18 December 1918. Tomlinson failed to get approval for an aircraft to allow him to attend the funeral. Frustrated with the Navy bureaucracy, Tomlinson resigned his commission in 1929. His letter of commendation for his command of VF-6B was sent via his new employer, Maddux Airways. He later returned to service during World War II.

[38] Annual Report, U.S. Fleet, 1928–29, pg. 66, Annual Reports of Fleets and Task Forces of the U.S. Navy, 1920–1941, Record Group 64: Records of the National Archives and Records Administration, National Archives and Records Administration.

[39] Annual Reports of the Navy Department for the Fiscal Year 1929 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1930), 598.

[40] Frederick M. Trapnell, Jr., and Dana Trapnell Tibbitts, Harnessing the Sky: Frederick “Trapp” Trapnell, the U.S. Navy’s Aviation Pioneer, 1923–52 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2015), 34.

[41] Marga R. Fritze, Blue Angels (Osceola, WI: MBI Publishing, 1996), 11; Naval Aviation News, January 1972, 2 (PDF available at history.navy.mil).