Minnesota I (Frigate)

1857-1901

The first Minnesota was named for the territory, named for a Lakota (Sioux) Native American word meaning “sky‑tinted water,” organized in 1849.

I

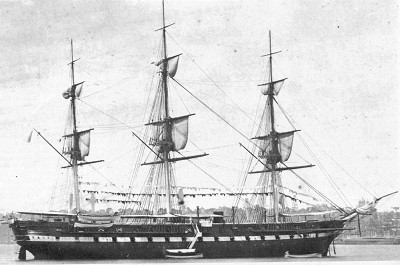

(Displacement 3,307; length 264' 8½"; beam 51'4"; draft 23'4"; speed 9¼ knots; complement 540; armament one 10-inch smoothbore, 26 9-inch, 14 8-inch; class Minnesota)

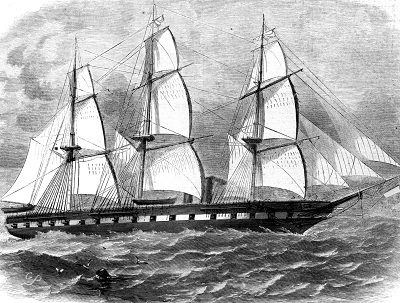

The first Minnesota, a wooden-hulled steam frigate, was authorized by an Act of Congress on 6 April 1854 and laid down in May 1854 at the Washington [D. C.] Navy Yard; launched on 1 December 1855; and sponsored by Miss Susan L. Mann, of Washington, D. C. She had cost $691.408.14 to build. She was commissioned on 21 May 1857, Capt. Samuel F. Du Pont in command.

The Second Opium War between the British, French, and Chinese, also known as the Arrow War, disrupted trade across East Asia (1856–1860). The U.S. consequently dispatched three additional ships to protect U. S. merchantmen trading in the region. Minnesota embarked U. S. Minister to China William B. Reed and sailed from Norfolk on 1 July 1857. Sloop-of-war Germantown and side-wheel steamer Mississippi also sailed independently for the Orient, from Norfolk and New York on 4 and 19 August, respectively.

Minnesota served with the East India Squadron, and then sailed from Hong Kong to bring Reed home with a newly negotiated Treaty of Commerce with the Chinese. Commodore Josiah Tattnall, Jr., Commander East India Squadron, ordered Capt. Du Pont to sail Minnesota via Muscat, Oman, where he was to remain for “such time as you may judge sufficient to shew [sic] the Ship, and to interchange the usual courtesies with the Authorities.” The ship visited Bombay [Mumbai], India (16 January–14 February 1859), but calm seas and limited wind compelled her to steam to Muscat. She anchored in the mouth of the cove there on 20 February. The anchorage proved dangerous because of its exposure to the sea, and the ship kept her fires banked throughout her visit. Minnesota fired the customary salute and landed a party.

Sultan Thuwaini bin Said al-Said of Muscat and Oman and “a large suite of officers” greeted the Americans with “great cordiality.” Du Pont and the Sultan agreed, through interpreters, to increase the trade between the two countries. The Sultan offered Du Pont an Arabian steed and a jeweled sword as gifts of his earnestness, but the captain tactfully noted that “he could not accept them.” Upon Du Pont’s return to the ship, he sent the Sultan a Sharp’s rifle and a Colt’s pistol with their accoutrements, as well as some “articles of my own calculated to please him.” Minnesota reached Table Bay, Cape of Good Hope, Cape Colony (South Africa) on 20 April, and returned to Boston Navy Yard on 2 June, where she decommissioned and remained in ordinary until the outbreak of the Civil War.

Minnesota was recommissioned on 2 May 1861, Capt. Gershom J. Van Brunt in command. Flag Officer Silas H. Stringham, Commander Atlantic Blockading Squadron, then broke his flag in the ship. She arrived at Hampton Roads on 13 May, and the following day captured blockade running schooners Delaware Farmer, Emily Ann, and Mary Willis, all laden with tobacco for Baltimore, Md., at Hampton Roads, Va. Union ships also seized blockade runner Argo, bound for the City of Bremen, from Richmond, Va. Minnesota took Confederate bark Winfred near Hampton Roads on 25 May.

Confederate schooner Savannah, Master T. Harrison Baker, sailed from Charleston, S.C., on 2 June 1861 and the following morning intercepted and seized Union brig Joseph of Rockland, Maine, which carried a load of sugar from Cárdenas, Cuba. Baker dispatched a prize crew that boarded the brig, apprehending her and transferring her master to the Southern vessel. Union brig Perry, Lt. Cmdr. Enoch G Parrott in command, sighted the two ships in company later that evening. Parrott showed his colors, but he suspected the ships of blockade running and privateering when Savannah raised and lowered a flag so quickly that he could not identify the colors. Perry fired a shot across the bow of Savannah, but she refused to heave-to. The Union ship wore round and passed her twice, and the Confederates then surrendered. Minnesota’s masthead lookout sighted Perry’s and Joseph’s sails at about 10:00 a.m. on 5 June. The ships hove to, and the Northerners dispatched a prize crew that boarded Savannah and sailed her, with Baker, his lieutenant, sailing master, purser, and 10 men, to New York.

Minnesota intercepted and captured bark Sally McGee off Hampton Roads on 26 June 1861, and schooner Sally Mears, Master George Richardson, of Yorktown, Va., also off Hampton Roads, on 1 July. Confederate brig Mary Warick struck her colors to the steam frigate in Hampton Roads on 10 July.

Stringham broke his flag in Minnesota during a joint Army‑Navy expedition against two Confederate forts that guarded Hatteras Inlet, N. C.: Fort Hatteras (15 guns, five not mounted at the beginning of the battle), and Fort Clark on the opposite side of the inlet (five guns). The forts guarded the main channel into Pamlico Sound, into which Confederate blockade runners supplied their troops ashore. Minnesota sailed from Hampton Roads in company with screw frigate Wabash, screw sloop Pawnee, screw gunboat Monticello, revenue cutter Harriet Lane, tug Fanny, and transports Adelaide and George Peabody, which embarked 880 soldiers of the 9th and 20th New York Volunteers, 99th (Union Coast Guard) New York Volunteers, and the 2d U.S. Artillery, Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler in command, on 26 August 1861. Fanny seized sloop Mary Emma as she attempted to run the blockade at the headwaters of the Manokin River, Md. (near Chesapeake Bay). Frigate Cumberland rendezvoused with the expedition en route to the forts, and the squadron anchored off Hatteras Inlet the following day.

Wabash, with Cumberland in tow, led the bombardment column, followed by Minnesota, when they opened fire on Fort Clark at 8:45 a.m. on 28 August 1861. Stringham maneuvered the three ships in a circle, and the enemy’s fire consequently fell short or over. The action ensured the survival of the vessels but prolonged the battle. Side-wheel steamer Susquehanna joined the expedition at about 11:00 a.m.. The Confederate gunners ran out of ammunition at 12:25 p.m., and abandoned the fort. While the battle raged, the other ships covered Adelaide and George Peabody as they landed the troops in surf boats above the forts. The heavy wind and breakers overturned some of the boats and disrupted the landings, but 318 men struggled through the turbulent sea before the Northerners postponed the landings. When the Confederates retreated from Fort Clark, some of the Union troops ashore occupied the fort, but the ships could not spot their advance through the smoke and continued to fire, wounding a Northern soldier before other men alerted the ships by waving the Stars and Stripes.

Stringham shifted fire to Fort Hatteras during the afternoon watch on 28 August 1861. The Confederate garrison began to fire sparingly to conserve their remaining powder and shot. The slackening enemy fire, and the difficulty in discerning their flag because of their tattered state and the dense smoke, persuaded the Union commanders that the Confederates intended to surrender, and Monticello closed the fort to determine if the defenders struck their colors and to sound the channel. The ship ran aground and Confederate guns hit her five times, wounding at least two crewmen but without seriously damaging the ship. The weather deteriorated and the ships opened the range overnight to ride out the swells and to replenish. Confederate Commodore Samuel Barron, CSN, who commanded the North Carolinian and Virginian coastal defenses, brought reinforcements from Fort Ocracoke, N. C., in gunboat Warren Winslow after dusk. Some of the gunboat’s sailors also landed to assist the defenders.

The weather calmed the following day, and the Union ships returned to battle, concentrating their fire on Fort Hatteras from a range of two miles, beyond the range of the garrison’s guns. The bombardment compelled the Confederate soldiers to seek cover in bomb shelters, and they surrendered shortly after 11:00 a.m. When the Southerners struck their flag, some of the lighter draft Union vessels entered the inlet to prevent additional reinforcements from reaching the forts.

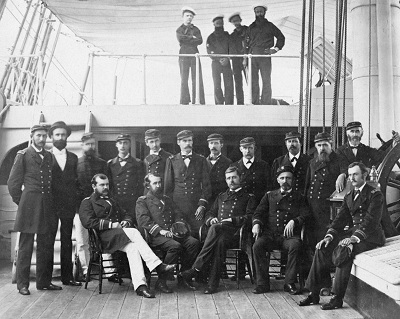

The Confederates suffered from four to seven killed and 20 to 40 wounded. The Union captured 691 prisoners. Butler boarded Minnesota with three of the prisoners at 2:30 p.m., and Stringham accepted the swords of Commodore Barron, Col. William F. Martin, CSA, 7th North Carolina Infantry, and Col. Andrews, CSA, the commanding officer of Fort Hatteras. The Northerners established a coaling and supply depot in the area for blockading ships, and their occupation of the forts enabled them to subsequently conduct operations inland. Flag Officer Louis M. Goldsborough relieved Stringham in command of the Atlantic Blockading Squadron on 23 September, selecting Minnesota as his flagship.

While blockading off Hampton Roads at 12:45 p.m. on 8 March 1862, Minnesota sighted Confederate steam battery Virginia and screw steamers Jamestown and Patrick Henry round Sewell’s Point and head toward Newport News. Capt. Van Brunt afterward reported to Secretary Welles that as the three ships appeared “into full broadside view I was convinced that one was the iron-plated steam battery Merrimack [Virginia], from the large size of her smoke-pipe.” Union Capt. John Marston, the commanding officer of screw frigate Roanoke and the senior officer present, signaled Minnesota to engage the enemy and she slipped her cables. A Confederate rifle battery on Sewell’s Point fired at Minnesota as she passed, and one shot crippled her mainmast. The ship returned fire with her broadside guns and forecastle pivot, seemingly ineffectively. The tide was running ebb, and Minnesota grounded when she reached a position about 1 ½ miles from Newport News. Van Brunt observed that the “bottom was soft and lumpy” and unsuccessfully attempted to force the ship over the mud bank.

Virginia meanwhile passed frigate Congress and rammed and sank sloop‑of‑war Cumberland. Virginia then turned upon Congress at about 2:30 p.m., and battered her into striking her colors an hour later. Van Brunt observed that the Southern ironclad threw “shot and shell into her with terrific effect, while the shot from the Congress glanced from her iron-plated sloping sides without doing any apparent damage.”

The three Confederate ships closed Minnesota at 4:00 p.m., but Virginia drew too much water to approach closer than a mile in the shallows. The enemy ironclad took a position off Minnesota’s starboard bow, but she fired ineffectually and only a single round passed through the steam frigate’s bow. Jamestown and Patrick Henry maneuvered to positions off Minnesota’s port bow and stern, respectively. Their fire damaged Minnesota and killed and wounded a number of her crewmen, but the Union ship returned fire and drove them off. Minnesota also fired upon Virginia with her 10-inch pivot gun but “without apparent effect,” Van Brunt tellingly reported. Toward twilight the Southern ships withdrew toward Norfolk.

The recoil from her broadside guns crowded Minnesota further upon the mud bank, and the commanding officer noted that his ship “seemed to have made for herself a cradle.” Steam tugs unsuccessfully worked to haul her off (10:00 p.m. on 8 March–4:00 a.m. on 9 March 1862). During the night, however, Lt. John L. Worden, the commanding officer of Monitor, received orders to render assistance, and he brought her alongside Minnesota at 2:00 a.m. on the 9th. Monitor’s arrival heartened Minnesota’s beleaguered sailors, and Van Brunt noted that “all on board felt that we had a friend that would stand by us in our hour of trial.”

Virginia steamed from the area of Craney Island and appeared into view of Minnesota’s lookouts at 6:00 a.m. on 9 March 1862. The frigate’s crew beat to quarters, but the Confederate steam battery sailed past Minnesota and Van Brunt called the retreat to enable his men to eat. Virginia turned into the channel toward the stranded Union ship and Van Brunt again ordered his crewmen to quarters. As the range closed to one mile, Minnesota opened fire with her stern guns and signaled Monitor to attack. Monitor steamed between Minnesota and Virginia and the two ironclads fired into each other, but Van Brunt compared the effectiveness of the two ship’s bombardment against their reinforced hulls to “so many pebblestones thrown by a child.”

The Confederate ironclad turned her attention to Minnesota. “I opened on her with all my broadside guns and 10-inch pivot,” Van Brunt reported, “a broadside that would have blown out of the water any timber built ship in the world.” Virginia fired from her rifled bow gun a shell which passed through the chief engineer’s stateroom, through the engineers’ mess room, amidships, and burst in the boatswain’s room, exploding two charges of powder. The round started a fire, but the ship’s second lieutenant led a party that extinguished the blaze.

Another shot from Virginia hurtled into the boiler of tugboat Dragon, which attempted to free Minnesota from the mud bank. The round exploded and caused severe damage to the tug. Dragon later completed repairs at Baltimore, Md.

Minnesota’s gun deck, spar deck, and forecastle pivot guns repeatedly hit Virginia, but the Confederate ship emerged from the smoke and attacked the Union ship. Monitor again positioned herself between Virginia and Minnesota and protected the frigate. Virginia shifted her position to continue the battle but grounded. The Confederate steam battery eased herself off the mud bank and stood down the bay. Monitor pursued her quarry, but Virginia came about and rammed Monitor and they fired a furious cannonade into each other.

Virginia, Jamestown, and Patrick Henry then all made for Minnesota. She lay fast, hard aground, the crewmen near exhaustion, and the frigate had fired most of her ammunition. “I then felt to the fullest extent my condition,” Van Brunt reported. The captain consulted with his officers and resolved to defy the enemy, and made preparations in the event of defeat to scuttle the ship rather than to strike. He ascended to the poop deck but watched with relief while the Confederate ships withdrew toward Craney Island at midday.

Van Brunt considered ordering his men to heave the 8-inch guns overboard, and to hoist out provisions and starting water, to lighten the ship. Steamer S.R. Spaulding and several tugs refloated the frigate a half mile until the tide fell during the afternoon watch, and then finally eased her off during the mid watch (2:00 p.m. on 9 March–2:00 a.m. on 10 March 1862). Monitor remained loyally near the frigate throughout her ordeal. Minnesota anchored for temporary repairs opposite Fort Monroe, Va. “It gives me great pleasure to say,” Van Brunt later wrote, “that during the whole of these trying scenes the officers and men conducted themselves with great courage and coolness.” Six men died on board Minnesota and 20 sustained wounds. The ship subsequently completed repairs at Portsmouth, Va., and Boston. The damage to Minnesota and the other wooden ships, and their failure to damage Virginia, underscored the vulnerability of wooden vessels against ironclads. Lt. Cmdr. Edward C. Grafton relieved Capt. Van Brunt as the commanding officer on 12 August. Cmdr. Napoleon B. Harrison relieved Lt. Cmdr. Grafton on 30 September.

For the next few years, Minnesota served as the flagship of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron (the Navy divided the Atlantic Blockading Squadron into the North and South Atlantic Blockading Squadrons on 29 October 1861), sailing frequently off Wilmington, N.C. Minnesota seized Confederate schooner Almira Ann, running the blockade with a cargo of timber, near the Chickahominy River, Va., on 17 May 1863. Lt. Joseph Fyffe relieved Cmdr. Harrison as the commanding officer on 19 November. Lt. Cmdr. John H. Upshur relieved Lt. Fyffe as the commanding officer on 9 December.

Screw sloop Tuscarora, screw steamer Keystone State, and screw gunboat Quaker City sighted a mysterious ship and pursued her but their prey seemingly eluded the three ships, overnight on 10 and 11 January 1864. Minnesota and screw steamers Aries, Daylight, and Governor Buckingham sailed in company on the blockading line in the waters off Wilmington on 11 January. Confederate blockade runner Ranger, Lt. George W. Gift, CSN, in command, carried a cargo from Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England, bound for Wilmington and attempted to enter the Cape Fear River. The Union ships chased the blockade runner and drove her aground near Lockwood’s Folly Inlet. The crewmen abandoned ship, but Southern sharpshooters “….completely commanded her [Ranger's] decks” with their fire, preventing the Northerners from refloating their prize. The blockaders consequently burned Ranger.

Union lookouts meanwhile spotted black smoke in the direction of Shallotte Inlet. Acting Lt. Edward F. Devens, in command of Aries (which had been withdrawn from her station in that quarter the previous night), investigated and discovered "…a fine-looking double propeller blockade runner, resembling Ceres [a British iron-hulled, screw-propelled blockade runner she had captured the previous month], beached and on fire between Tubb’s and Little River Inlets…" The Confederates drove the blockade runner ashore and set the ship alight to prevent her capture following the flight from Tuscarora, Keystone State, and Quaker City.

Once more, Confederate snipers prevented Union boarding parties from clambering onto the steamer to extinguish the flames and take possession of their prize. The Southern soldiers withdrew and the following day, Northern sailors boarded the vessel and identified her as Vista, a sister ship of Ceres. Serious damage to Vista’s hull made it impossible to refloat the blockade runner, and the boarders claimed only her two anchors as booty.

A Union army expedition attempted to seize a Confederate encampment and a store of tobacco on Pagan Creek near Smithfield, Va., on 1 February 1864. Minnesota deployed launches that embarked some of the soldiers, in company with other vessels including converted ferry boat Commodore Morris. Southern sharpshooters defeated the landing with the Union loss of army gunboat Smith Briggs.

Acting Master James M. Williams of screw steamer Commodore Barney led a boat expedition up Chuckatuck Creek, Va., against some Confederate soldiers reported to be in the vicinity on the night of 29 and 30 March 1864. Acting Master Charles B. Wilder of Minnesota led a detachment of sailors from the ship that reinforced Williams. The men landed at Cherry Grove shortly before dawn, silently surrounded the enemy headquarters, and captured 20 prisoners. Rear Adm. Samuel P. Lee, Commander North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, reported to Secretary Welles that “…it gives me pleasure to commend the energy and zeal displayed by these officers in planning and carrying out to a successful termination an expedition of no little difficulty.”

Confederate submarine H.L. Hunley sank Union sloop-of-war Housatonic with a spar torpedo, packed with explosive powder and attached to a long pole on her bow, off Charleston on the night of 17 February 1864. H.L. Hunley also sank. The attack caused widespread concern among Union sailors.

The Confederates deployed torpedo boat Squib, Lt. Hunter Davidson, CSN, in command, against Minnesota while the blockader lay at anchor off Newport News, at about 2:00 a.m. on 9 April 1864. Squib measured approximately 35 feet in length and drew only three feet of water, characteristics that enabled her to maneuver in coastal waters inaccessible to larger ships. Minnesota’s officer of the deck saw a small boat at a range of 150 to 200 yards, just forward of the port beam. He hailed the unknown vessel, and a Confederate sailor replied “Roanoke.” Acting Ensign James Birtwistle ordered Squib to stand clear, and Davidson responded, “Aye, aye.”

Birtwistle could not discern a visible means of propulsion for Squib, but the intruder continued to rapidly close Minnesota. The Union ship attempted to open fire, but the decreasing range prevented her from bringing a gun to bear. Squib rammed the ship in her port quarter and exploded the 53 pound torpedo charge. Acting Master John A. Curtis, CSN, Squib’s executive officer, closed his eyes and described “opening them in about a second, I think, I never beheld such a sight before, nor since. The air was filled with port shutters and water from the explosion, and the heavy ship was rolling to starboard, and the officer of the deck giving orders to save yourselves and cried out ‘Torpedo, torpedo!’”

The explosion imperiled Squib as Minnesota’s roll pulled the torpedo boat beneath the frigate’s port quarter, but as the ship healed back the attacker broke free, and Curtis leapt onto the bow of his vessel and pushed her away from Minnesota. Union sailors fired muskets at the Confederate torpedo boat as she escaped. Union tug Poppy lay nearby did not have steam up and was unable to pursue Squib, which retired up the James River. Davidson attained the rank of Commander in recognition of the daring deed.

The attacks on Housatonic and Minnesota intensified Union fears concerning submarines. “In these days of steam and torpedoes,” U.S. Consul at Malta William Winthrop wrote Secretary of State William H. Seward, “you may rest assured that outlying picket boats and a steam tug at all hours ready to move are not sufficient protection for our ships of war, where a squadron is at anchor. They require something more, and this should be in having their own boats rowing round all night, so that in a measure every ship should protect itself. If this precaution be not taken, any vessel in a dark and foggy night could be blown out of the water, even while a watchful sentry on board might still have his cry of ‘All’s well’ yet on his lips as the fiendish act was accomplished.”

Rear Adm. Lee led Union ships and soldiers in a thrust up the Nansemond River, Va., to search for Confederate troops believed to be in the area, and to capture Squib (13–14 April 1864). Acting Lt. Charles B. Wilder led two launches from Minnesota, which joined converted ferryboats Commodore Barney, Commodore Morris, Commodore Perry, Shokokon, and Stepping Stones. Confederate snipers killed Wilder near Smithfield, and Lt. Cmdr. Upshur afterward noted that “true to the reputation he had won among his shipmates for promptness and gallantry, he fell while in the act of firing a shot at the enemy.” The raiders took a handful of prisoners, but Squib again eluded capture by slipping from Smithfield toward Richmond on 10 April.

During the spring of 1864, the Confederates considered a bold plan to divert Union forces from the fighting in Virginia that included an operation to free the estimated 15,000 Southern prisoners held at a Northern prison at Point Lookout, Md. Maj. John Tyler, CSA, wrote to Maj. Gen. Sterling Price, CSA, explaining the scheme. Lt. Gen. Jubal A. Early, CSA, Commander Second Corps, was to capture Baltimore, and hold the city with his infantry while his cavalry assailed Point Lookout. The naval portion comprised a voyage by Capt. John T. Wood, CSN, and five gunboats carrying 20,000 ‘stand of arms’ to rendezvous with Early at the prison. In the event of victory, the Confederates considered a further assault to seize Washington, D.C. “This I regard as decidedly the most brilliant idea of the war,” Tyler concluded.

Lt. Moses S. Stuyvesant, who had recently assumed command of Minnesota, learned of the plan from intelligence gained in the area of the ship’s operations. Stuyvesant telegraphed Secretary Welles, who alerted the army, during the evening of 18 July 1864: “The commanding general at this point deems reliable the following information which he has just obtained from four refugees [Confederate deserters]. That 800 Sailors and Marines, under John T. Wood, left Richmond on the 7th or 8th of July, to man two armed blockade runners at Wilmington, N.C., for the purpose of attempting the release of prisoners confined here. Will telegraph to senior officer at Fortress Monroe.” Unbeknownst to Stuyvesant, however, the inadequate Southern security precautions alarmed Confederate President Jefferson F. Davis, who feared that the Northerners learned of the attack, and on 10 July he recommended its cancellation. The Confederates subsequently ended the operation.

Commodore Joseph Lanman relieved Lt. Stuyvesant as the commanding officer of Minnesota on 1 October 1864. Minnesota took part in amphibious operations at Fort Fisher, located at one of the two entrances of Cape Fear River and which guarded Wilmington (23–25 December 1864). Screw steamer Wilderness towed powder boat Louisiana, Lt. Cmdr. Alexander C. Rhind in command, to a position about 250 yards from Fort Fisher overnight (23–27 December). Rhind and his crewmen set the fuses and a fire in the stern and escaped in a small boat to Wilderness. The clock mechanism failed to ignite the powder at the set time of 1:18 a.m., but the fire touched off the charges several minutes later. The huge explosion shook the Confederates ashore but failed to materially harm the fort.

Rear Adm. Lee retired the ships of the expedition to avoid the blast to Beaufort, N.C. The ships rendezvoused in an area 12 miles from the fort, and at 11:30 a.m. on 24 December 1864, they formed in line of battle, the fort bearing west-southwest, nearly seven miles. Ironclad steamer New Ironsides led Line No. 1, including monitors Canonicus, Mahopac, Monadnock, and Saugus, to anchorages at a range of 1,000 yards from the fort and they opened fire.

Minnesota led Line No. 2, the main column of wooden ships, followed by screw sloop-of-war Mohican, frigate Colorado, and then additional men-of-war. Minnesota sheered out of the line at about 1:00 p.m., anchored at a position 2,100 yards from the fort, and opened fire. Mohican sheered out of line and anchored ahead of Minnesota, and Colorado followed suit behind Minnesota. The other vessels took up their bombardment positions in succession. The Confederates initially shot at the ships, but the Union cannonade compelled most of the defenders to seek shelter in their bombproofs, though some gunners resolutely fired their heavier pieces at the attackers. Five 100-pounder Parrott guns burst on board five different Union ships, but the Northerners otherwise suffered few casualties. Maj. Gen. Butler had intended to land his troops in the wake of the explosion without meeting heavy resistance, but the transports did not arrive from Beaufort until dusk, and the attackers consequently postponed the landings until the following day.

The Union ships opened fire on Fort Fisher again at 10:30 a.m. on 25 December 1864, Christmas Day. Porter directed Minnesota to lead the line of wooden ships, because she was “the slowest and least manageable.” Mohican stood in, but Minnesota slowly gained her position and Porter verbally ordered Cmdr. Daniel Ammen, the commanding officer of Mohican, “not to take position until further orders.” Minnesota reached her anchorage and commenced firing, and one-by-one the other wooden ships took their positions and subjected the bastion to a tremendous onslaught of shot and shell.

“The whole of the interior of the fort,” Lt. Aeneas Armstrong, CSN, afterward recalled, “which consists of sand, merlons, etc., was as one eleven-inch shell bursting. You can now inspect the works and walk on nothing but iron.” Despite the fury of the gunfire, the defenders held their positions. The ships also supported Butler while he landed troops to the north of the fort near Flag Pond Battery, but the general considered the fort too strong for assault and embarked the soldiers by 27 December 1864. Lee kept his warships in the area and frequently shelled the Confederates to disrupt their efforts to repair the fort, while the transports returned the troops to Hampton Roads. Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, USA, general-in-chief of all Union armies, relieved Butler of his command, replacing him with Maj. Gen. of Volunteers Alfred H. Terry.

The Northerners returned for a second assault against Fort Fisher early on the morning of 13 January 1865. Rear Adm. David D. Porter commanded 58 ships, and Terry led nearly 8,000 soldiers, primarily from the XXIV and XXV Corps, augmented by a naval landing force of 2,000 Sailors and Marines. The Confederate garrison numbered almost 1,900 men. The Union ships ferociously blasted the enemy, and Porter afterward attested to the effectiveness of the ironclads: “It was soon quite apparent that the iron vessels had the best of it; traverses began to disappear and the southern angle of Fort Fisher commenced to look very dilapidated.” Terry landed 8,000 men on the peninsula beyond the range of the guns in the fort and raised breastworks to defend his encampment. The ships renewed the barrage the following day. “It was beyond description, no language can describe that terrific bombardment,” Maj. Gen. William H.C. Whiting, CSA, recalled. The attackers repeated their shelling the next morning, ultimately inflicting nearly 300 casualties and knocking out many of the fort’s guns.

Porter ordered the ships to cease fire at 3:00 p.m. on 15 January 1865, and the troops attacked Fort Fisher. The sailors formed in three divisions, under the command of Lieutenant Commanders Charles H. Cushman, James Parker, Jr., and Thomas O. Selfridge, respectively, and the marines in a fourth division led by Capt. Lucien L. Dawson, USMC, of Colorado. Minnesota contributed a landing force of 240 men. The bluejackets and marines of these divisions suffered grievous losses while they advanced across relatively open ground into the teeth of the Southerner’s fire, which ploughed “lanes in the ranks.”

“About five hundred yards from the fort the head of the column suddenly stopped,” Ensign Robley D. Evans later recalled, “and, as if by magic, the whole mass of men went down like a row of falling bricks…The officers called on the men, and they responded instantly, starting for-ward as fast as they could go. At about three hundred yards they again went down, this time under the effect of canister added to the rifle fire. Again we rallied them, and once more started to the front under a perfect hail of lead, with men dropping rapidly in every direction.”

The ships renewed their fire and enfiladed the Confederates, their rounds crashing into the defenders and enabling the attackers to storm the ramparts. Some of the ships shifted their shooting to churn-up the river bank behind the fort to prevent reinforcements from entering the bastion. The Northerners lost more than 1,000 men but carried the works. Assistant Surgeon William Longshaw, Jr., of Minnesota was the only officer from the ship who died in the battle, though a number of others including Acting Ensigns Birtwistle and Frederick A. O’Connor, together with Acting Master’s Mate Joseph M. Simms, sustained wounds. “I was much pleased with the manner in which he handled his ship and fired throughout the action,” Porter observed of Lanham, “the whole affair on his part being conducted with admirable judgment and coolness.” Fort Fisher’s main magazine mysteriously exploded shortly after dawn on 16 January, killing at least 200 Federals and 200 Confederates. Each side blamed the other for the tragedy, noting that many men, Northerners and Southerners alike, drank plundered spirits following the fall of the bastion, but conclusive evidence about the cause of the blast failed to emerge. The operation closed Wilmington, denying the Confederates the use of the valuable port.

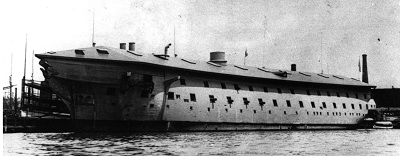

Minnesota was decommissioned at Portsmouth, N.H., on 16 February 1865. She was recommissioned on 3 June 1867, Commodore James Alden in command, and made a cruise with midshipmen to Europe. She was placed in ordinary at the New York Navy Yard, Brooklyn, N. Y., on 13 January 1868. Recommissioned on 12 June 1875, Capt. Andrew W. Johnson in command, she was classified a "training-ship" for naval apprentices and remained at the New York Navy Yard. The ship’s original battery changed more than once to keep pace with improvements in ordnance, and in 1882 she mounted one 60 pounder breech-loading rifle, 24 9-inch smoothbores, two 20 pounder breech-loading rifles, and four smaller guns. Minnesota served as a receiving ship in New York (1888–1889). In October 1895, she was loaned to the Massachusetts Naval Militia, continuing that duty until she was sold for $25,738.32 to Thomas Butler & Company, of Boston, in August 1901. The ship was subsequently burned for ‘old junk’ at Eastport, Maine.

Mark L. Evans

Updated, Robert J. Cressman

28 March 2024