H-083-1: "Hit 'em Harder!"

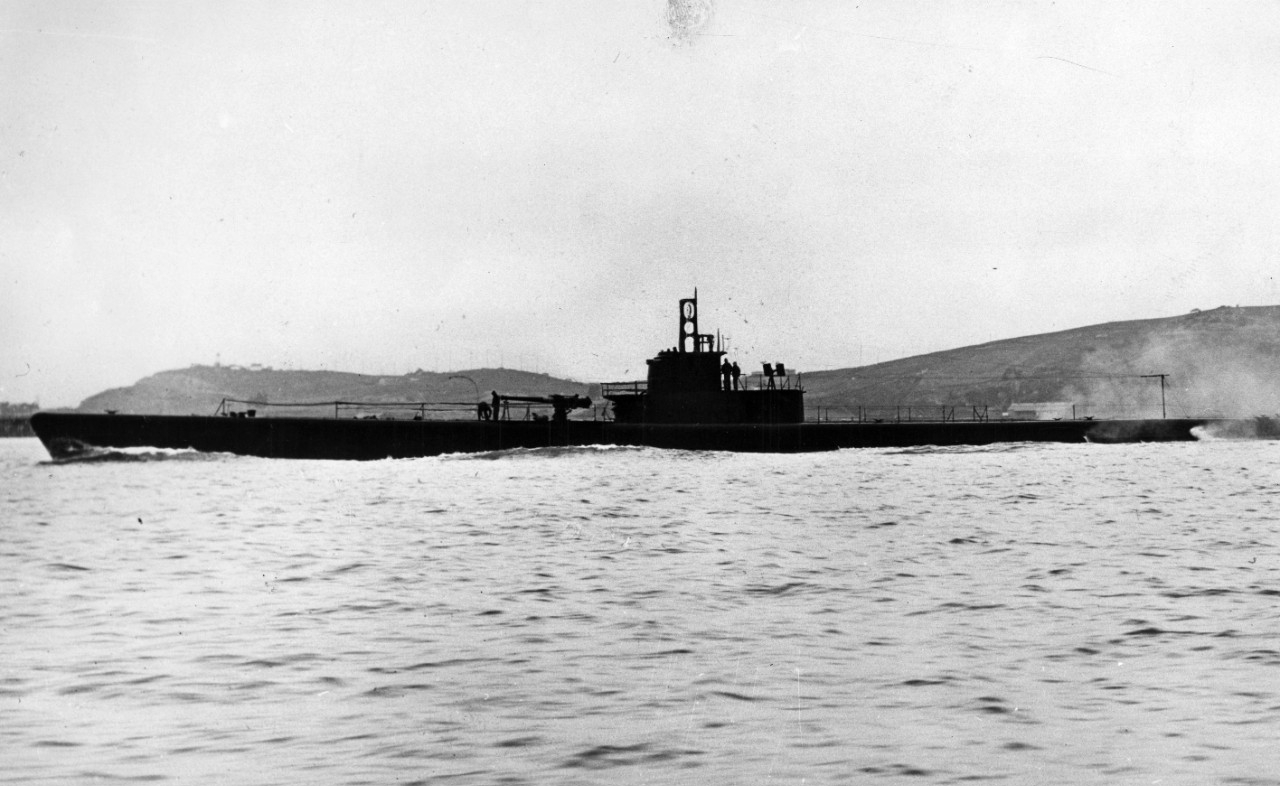

Harder (SS-257) was a Gato-class fleet submarine laid down on 1 December 1941 at the Electric Boat Company in Groton, Connecticut. The submarine was launched on 19 August 1942 and commissioned on 2 December 1942 under the command of Commander Samuel D. Dealey (U.S. Naval Academy [USNA] ’30).

Designed to operate with the U.S. Battle Fleet by scouting ahead, the Gato-class submarines were relatively fast on the surface (21 knots). This speed was adequate for the World War I–era battleships that comprised the Battle Fleet prior to Pearl Harbor, but was not sufficient to keep up with the new fast battleships and aircraft carriers that came on line after Pearl Harbor. As a result, U.S. submarines found their greatest success in World War II engaged in unrestricted submarine warfare against Japanese cargo ships and tankers, choking off the supply of raw materials for Japanese industry.

Harder displaced 1,549 tons surfaced and 2,462 tons submerged and was 311 feet in length. Harder’s diesel engines could propel it at 21 knots on the surface, while its electric motors were capable of 9 knots submerged. The submarine had a cruising range of 11,000 nautical miles on the surface for up to a 75-day patrol. Submerged endurance was 48 hours at 2 knots. Harder’s originally designed complement was 6 officers and 54 enlisted, but under wartime conditions it would have up to 80 on board. Harder had six 21-inch torpedo tubes forward and four aft, with a total of 24 torpedoes. Deck guns on Gato-class submarines would vary during the war; Harder originally had a 3-inch, 50-caliber deck gun that would be augmented with 40-millimeter Bofors guns and 20-millimeter Oerlikon guns.

Samuel David Dealey was born in Dallas, Texas, in 1906 and graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1930. According to the Lucky Bag (the Naval Academy yearbook) the greater the stress, the more he smiled. He initially served aboard battleship Nevada (BB-36) and then for a short time on the destroyer Rathburne (DD-113) before reporting to Submarine School in New London, Connecticut, in the summer of 1934. He subsequently served aboard the submarines S-34 (SS-139), S-24 (SS-129), Nautilus (SS-168), and Bass (SS-164). In May 1937, he was assigned as aide to the executive officer of Naval Air Station Pensacola, Florida.

In the summer of 1939, Dealey was assigned as executive officer of the battleship Wyoming (BB-32), which was serving as a gunnery training ship, and then as executive officer of the destroyer Reuben James (DD-254) until April of 1941. (Reuben James would be sunk by U-552 on 31 October 1941 during the undeclared war in the Atlantic between the U.S. Navy and German submarines prior to Pearl Harbor [see H-Gram 001]).

Lieutenant Dealey reported to Experimental Submarine Division 1 as prospective commanding officer of S-20 (SS-125) before relieving Lieutenant John P. Cromwell (future posthumous Medal of Honor recipient for his actions aboard Sculpin [SS-191] in 1943). Operating out of New London, S-20 tested new equipment and tactics. Dealey was temporarily promoted to lieutenant commander in June 1942 and assigned as precommissioning commanding officer of Harder, then under construction. He was temporarily promoted to commander in December 1942 and assumed command of Harder upon commissioning on 2 December 1942.

Upon completion of shakedown training off New London, Harder commenced a transit to Pearl Harbor via the Panama Canal. While transiting on the surface through the Caribbean on 2 May 1943, Harder was accidentally attacked by a U.S. Navy PBY Catalina flying boat. After the PBY machine-gunned Harder’s starboard side, Harder crash-dived and maneuvered radically, causing two bombs dropped by the PBY to miss.

First War Patrol

Harder departed Pearl Harbor on 7 June 1943 en route to operations along the east coast of Honshu, Japan, sometimes as close as six nautical miles off the coast. During this patrol, Harder would suffer from significant engine problems as well as the unreliable torpedoes that plagued the U.S. submarine force in 1942–43. On 22 June 1943, Harder attempted its first attack on a Japanese convoy, firing four torpedoes at a Japanese tanker. The first torpedo prematurely exploded only 15 seconds into its run, giving away Harder’s position to the Japanese escort, although one of the other torpedoes did damage the tanker. In diving to avoid the anticipated counterattack, Harder hit the bottom hard, severely damaging its JK-QC sonar and jamming itself in the mud as 12 depth charges detonated overhead. It took several attempts and almost four hours to break free of the bottom.

On the morning of 23 June, three Japanese escort ships attempted to trap Harder, but the submarine was able to escape. Harder then stalked the auxiliary seaplane transport Sagara Maru, which sighted Harder’s periscope and opened fire. Harder fired four torpedoes, one of which hit. Given the close proximity to Japanese airfields, Dealey chose not to pursue Sagara Maru. The Japanese destroyer Sawakaze took Sagara Maru in tow and beached the transport to prevent sinking. (On 4 July 1943, Pompano [SS-181] hit the beached Sagara Maru with two torpedoes, causing the Japanese to give up trying to salvage the vessel.)

Harder would subsequently conduct seven attacks on three convoys but again suffer a premature torpedo detonation while other torpedoes ran erratic or missed. On 25 June, Harder attacked a three-ship convoy and possibly scored one hit out of seven torpedoes fired. On 29 June, Harder damaged a cargo ship and an oiler before incurring a near miss from a bomb from a Japanese aircraft.

Harder ended its first patrol at Midway on 7 July with one engine out of commission. During the war, Harder would get credit for sinking three ships totaling about 15,400 tons on its first war patrol, but postwar analysis revised this to only one ship of 7,189 tons. The patrol was rated as successful, and Dealey would be awarded the first of his four Navy Crosses.

Second War Patrol

Harder departed Pearl Harbor on 24 August 1943 to again operate off the coast of Honshu and once again suffered significant engine trouble. On 9 September, Harder attacked the cargo ship Koyo Maru. Only one of three torpedoes hit, and it was a dud, but it caused enough flooding that Koyo Maru later sank under tow. On 11 September, Harder sank the cargo ship Yoko Maru and then withstood an inaccurate depth-charge attack by the convoy escort.

On 13 September, Harder attempted a submerged attack on two cargo ships, firing two torpedoes just as a Japanese plane dropped a bomb that was a near miss. Harder was then subjected to a sustained attack by 59 depth charges and aerial bombs that lasted almost 48 hours, nearly exhausting Harder’s batteries. On 19 September, Harder sank the cargo ship Kachisan Maru and then withstood a determined depth-charge attack, several of which detonated quite close.

On 22 September, Harder attacked a tanker at close range, but all three torpedoes passed under the tanker without exploding. Japanese aircraft responded almost immediately, with one bomb close enough to cause significant damage. On 23 September, Harder sank the freighter Kowa Maru and the tanker Daishin Maru, but dud torpedoes spoiled further attacks on a five-ship convoy on 28 September. On 29 September, Harder shot up two armed trawlers with surface gunfire, but both made an escape. Harder returned to Midway on 4 October. Postwar analysis credited Harder with five ships sunk totaling 15,252 tons. Dealey was awarded a second Navy Cross.

Third War Patrol

Harder commenced its third war patrol on 30 October 1943 as part of a three-submarine wolfpack with Snook (SS-279) and Pargo (SS-264). The mission was to conduct operations around the Marianas Islands to forestall Japanese attempts to reinforce Tarawa prior to landings scheduled there for late November 1943. Early wolfpack operations suffered from communications challenges, and the three subs quickly became separated. On 12 November, Harder claimed to have sunk an unidentified cargo ship and an armed trawler.

On 19 November, Harder attacked a three-ship convoy, sinking the passenger cargo ship Hokko Maru and then five minutes later hitting the cargo ship Udo Maru, which subsequently sank despite Japanese efforts to tow it. Later in the day, Harder fired four torpedoes at the lone survivor of the convoy, the ore carrier Nikko Maru, but all four torpedoes ran under the ship without exploding. An hour later, Harder attacked Nikko Maru again, hitting it with two torpedoes, but the ship refused to sink, and the crew refused to give up. All told, Harder fired 11 torpedoes at Nikko Maru for just two hits. Four torpedoes ran circular and others were erratic. Nikko Maru finally succumbed to worsening sea conditions.

With all torpedoes expended, Harder returned to Pearl Harbor on 30 November and then to Mare Island to have its troublesome engines replaced. Dealey was awarded another Navy Cross, and postwar analysis credited Harder with three ships sunk totaling 15,250 tons.

Fourth War Patrol

Harder returned to Pearl Harbor from Mare Island on 27 February 1944. The submarine departed on 16 March in company with Seahorse (SS-304) to provide lifeguard service for carrier strikes on Woleai in the Western Caroline Islands. While conducting reconnaissance of Woleai, Harder was damaged by a bomb but continued on patrol.

On 1 April, Harder commenced a daring rescue attempt of downed pilot Lieutenant (j.g.) John R. Galvin from an unnamed island west of Woleai. Galvin belonged to Fighter Squadron 8 (VF-8) off Bunker Hill (CV-17). Despite Japanese sniper fire and pounding surf, Dealey nosed Harder right up against the reef, touching bottom, while launching a rubber raft tethered to the submarine. Lieutenant Samuel M. Logan (USNA ’42, graduated early in 1941 as first in his class), Motor Machinist’s Mate First Class Francis X. Ryan, and Ship’s Cook First Class J. W. Thomason volunteered to wade into the water, pushing and towing the raft toward the downed aviator. An aircraft dropped another raft, which Galvin climbed into. He tried unsuccessfully to paddle against the tide.

After 30 minutes, the rescue party reached Galvin just as a float plane landed and inadvertently cut the tether line. Gunner’s Mate First Class Freeman Paquet then swam another line to the rescue party, who were then all hauled back to Harder with the pilot. All four members of the rescue party were subsequently awarded the Navy Cross.

On 13 April, a Japanese aircraft sighted Harder 200 nautical miles south of Guam, reporting the position to the destroyer Ikazuchi, which then commenced to hunt for Harder. As Ikazuchi closed in for the attack, rather than diving, Dealey waited as the range closed to 900 yards before firing torpedoes, hitting with two of them. As Ikazuchi sank, its depth charges exploded, leaving no survivors. (Earlier in the war, in the aftermath of the Battle of the Java Sea, Ikazuchi had rescued more than 400 survivors of the British cruiser HMS Exeter and destroyer HMS Encounter.) Dealey’s report of the sinking would become famous: “Expended four torpedoes and one Jap destroyer.”

On 17 April, Harder sank the freighter Matsue Maru. On 20 April, Harder shelled the airfield on Woleai before finishing its patrol at Fremantle, Australia, on 3 May 1944. Dealey was awarded a fourth Navy Cross. After the war, Harder was credited with sinking two ships totaling 9,011 tons on this patrol.

Fifth War Patrol

Prior to April 1944, U.S. submarines would normally try to avoid Japanese destroyers as they presented a serious threat to the submarine. However, thanks to Ultra code-breaking intelligence it became apparent that Japan was suffering an acute shortage of destroyers, having lost many in the battles around the Solomon Islands, and was having an increasingly difficult time providing escorts for convoys and screens for fleet operations. Beginning in April 1944, sinking destroyers became a higher priority than sinking cargo ships or even tankers. With this strategy in mind, Dealey lobbied for and was given a patrol area outside the major Japanese fleet anchorage at Tawi Tawi off the northeast coast of Borneo. (The reason for the Japanese using this anchorage was that it was close to the source of fuel oil, which had become increasingly scarce in the Japanese home islands thanks to submarines sinking so many tankers. Tarakan crude from Borneo could be burned in ships without need of refining, although it was especially volatile.)

Harder departed Fremantle on 26 May, initially in company with Redfin (SS-272) for patrol in the Celebes Sea. Harder took station near Tawi Tawi near the Sibutu Passage between the northeastern tip of Borneo and Mindanao, Philippines. On the night of 6 June, Harder sighted a convoy of three tankers escorted by two destroyers in the Sibutu Passage. While getting into firing position on the surface, Harder was illuminated by the moon. The destroyer Minazuki turned to attack Harder. Dealey fired three torpedoes from his stern tubes at the onrushing destroyer, hitting with two. Minazuki went down in five minutes with its own depth charges detonating and killing all but 45 of its crew, including the commanding officer. As the second destroyer closed in, Harder fired all six bow tubes, all of which missed. Harder was then held down by a depth-charge attack that allowed the tankers to escape.

On the morning of 7 June, Harder was spotted by a Japanese aircraft, which directed the destroyer Hayanami in for an attack. As the destroyer closed in, Harder made a hard turn undetected by the destroyer and fired three torpedoes, two of which struck amidships. Hayanami suffered a devastating magazine explosion and sank in under one minute, sustaining 208 losses among the crew and only 45 survivors. Harder then endured another depth-charge attack.

On the evening of 7 June, Harder approached the Japanese-held Borneo coastline and launched two folding canoes, which picked up six Australian special operations soldiers of the Special Reconnaissance Department Z Unit and brought them aboard. (Two Australians were already on board to assist this operation.)

By 8 June, numerous destroyers had sortied from Tawi Tawi, hunting for Harder. Dealey was not foolhardy at all, and in several encounters he chose to disengage rather than attack if he didn’t like the set up. However, on the evening of 8 June, Harder encountered several destroyers searching in line abreast. Dealey chose a position where he had a chance of hitting two overlapping targets with one spread of torpedoes. The first torpedo missed ahead of the nearest destroyer, but the second and third hit the destroyer Tanikaze, resulting in a massive boiler explosion, causing it to sink almost immediately. Of Tanikaze’s crew, 126 were rescued and 114 were killed, including the commanding officer, who died of wounds after rescue.

Dealey observed what he described as a blinding flash from a torpedo hit on the far destroyer. He claimed and was given credit during the war for sinking this unnamed destroyer, which does not correlate to any Japanese losses. (Of note, on 5 June 1942, the day after the main Battle of Midway, Tanikaze was sent back to see if the carrier Hiryu was still afloat [it wasn’t]. As a result, Tanikaze was subject to an attack by 61 U.S. dive bombers, managing to avoid every bomb while shooting down one Dauntless dive bomber and losing only six crew members to splinters. Tanikaze was then bombed by several B-17 bombers and avoided all the bombs; one of the B-17s accidentally jettisoned its extra fuel tanks and was lost, while a second B-17 just disappeared on the way back to Midway.)

On 10 June, Harder sighted a Japanese force of three battleships, four cruisers, and a destroyer screen. Once again, alert Japanese aircraft spotted Harder and vectored in a Japanese destroyer. Dealey fired a down-the-throat shot at the oncoming destroyer and believed he hit with two torpedoes, as Harder then passed 80 feet under the sinking destroyer. Dealey was given credit during the war for sinking this unnamed destroyer; however, it does not correlate to any Japanese losses. It’s possible this destroyer was heavily damaged (but I can’t find which one it might have been).

On 11 June, Harder closed in to observe the Tawi Tawi anchorage, spotting several cruisers and destroyers but noting no battleships. He then proceeded to safer waters and provided a vital reconnaissance report to Admiral Raymond Spruance in the run-up to the Battle of the Philippine Sea. Harder’s depredations around Tawi Tawi so rattled the Japanese that Admiral Jisaburō Ozawa was convinced there were numerous submarines around the anchorage, resulting in a premature departure of forces, which upset the timing for the oncoming battle (see H-gram 032).

Harder arrived at Darwin, Australia, on 21 June and loaded additional torpedoes and quickly got underway with Rear Admiral Ralph W. Christie embarked. Christie was the Commander, Submarines, Southwest Pacific. Harder was directed to intercept a Japanese ship carrying nickel ore as well as a damaged cruiser returning from the Battle of the Philippine Sea, but was unsuccessful in both, primarily due to alert Japanese aircraft. Harder returned again to Darwin on 3 July, and this foray into the Flores Sea was counted as part of the fifth war patrol. Upon arrival, General Douglas MacArthur presented Dealey on the spot with an Army Distinguished Service Cross (equivalent to a Navy Cross).

Sixth War Patrol

After five arduous war patrols, the executive officer of Harder was concerned that Dealey was showing signs of excessive fatigue. Other officers made the same observation. Rear Admiral Christie met with Dealey and advised that he relinquish command, but with a rotation of about a third of Harder’s crew coming up, Dealey believed he had a responsibility to ensure the new crew members were properly broken in. Christie acquiesced to Dealey’s desire and agreed to let Dealey take one more patrol.

Harder departed Fremantle on 5 August 1944 with Dealey in tactical command of the three-submarine wolfpack, which also included Haddo (SS-255, commanded by Lieutenant Commander Chester Nimitz Jr.) and Hake (SS-256). The mission was to patrol off the west coast of the Philippines. Receiving intelligence derived from Ultra code breaking, Dealey was informed that a Japanese convoy was due to depart from Mindoro. Lying in wait, Dealey’s wolfpack was joined by Guitarro (SS-363), Raton (SS-270), and Ray (SS-271). The convoy sortied in the early morning of 21 August. In the feeding frenzy that followed, four ships of the convoy were sunk with no damage to any of the submarines, despite determined Japanese depth-charge attacks. Haddo sank two ships, while Guitarro and Ray each sank one—however, Ray’s attack caused the convoy to steer away from Harder.

After the attack on the convoy, Harder and Haddo moved north toward Manila Bay, intercepting three 900-ton escort ships that had survived the attack on the convoy. (The Japanese term is kaibōkan meaning “escort ship”—these were somewhat smaller than a U.S. Navy destroyer escort but similarly armed, and in some accounts are referred to as “frigates.”) In a coordinated attack, Harder torpedoed Matsuwa and Hiburi while Haddo torpedoed Sado. However, all three ships remained afloat. At daybreak, Harder finished off Matsuwa (134 killed) while Haddo finished off Sado (73 killed). Haddo missed a shot to finish off Hiburi, so Harder then sank it (154 killed).

Harder and Haddo then moved farther north, near Dasol Bay on the west coast of Luzon, to rendezvous with Hake. On the morning of 23 August, Haddo expended its last torpedo on the elderly destroyer Asakaze, which was under tow by the tanker Niyo Maru. The Japanese tried to save Asakaze, but it subsequently sank. However, Dealey did not know this and believed Asakaze may have been towed into Dasol Bay. Haddo was detached. In the meantime, the Japanese dispatched the escort ship CD-22 and the patrol ship PB-102 from Cavite in response to a call for help from Niyo Maru, which had taken refuge in Dasol Bay.

At 0630 on 24 August, Harder and Hake were positioned outside Dasol Bay. The skipper of Hake, Lieutenant Commander Frank Haylor, sighted a three-stack ship and a smaller one exiting Dasol Bay and misidentified them as the old Thai destroyer Phra Ruang (Thailand was allied with Japan at the time) and a minesweeper. The minesweeper was CD-22 and the Thai destroyer was PB-102, which was actually the ex–Clemson-class destroyer Stewart (DD-224). Stewart had been significantly damaged in a battle with Japanese destroyers near Bali in February 1942. While in the floating dry dock at Surabaya, Java, Stewart fell off the blocks. When Stewart could not be righted, demolition charges were detonated and then the ship was hit by a Japanese bomb before the dry dock itself was scuttled. The Japanese subsequently raised the dry dock and repaired and modified Stewart (four stacks to three), putting it in service as PB-102, which resulted in multiple sightings late in the war of what appeared to be an old U.S. destroyer operating far behind Japanese lines.

As CD-22 and PB-102 came out of Dasol Bay, they sighted a periscope and turned to attack. Hake then commenced an approach on PB-102. Upon sighting two periscopes, PB-102 turned back and escorted Niyo Maru into Dasol Bay. CD-22 kept on an attack profile. The skipper of Hake didn’t like the setup and turned away, at this point sighting the periscope of Harder between Hake and CD-22. In American accounts, this was the last seen of Harder. Hake reported hearing 15 depth charges in quick succession shortly thereafter. Hake returned to the area later in the afternoon but only found some marker buoys and no sign of Harder.

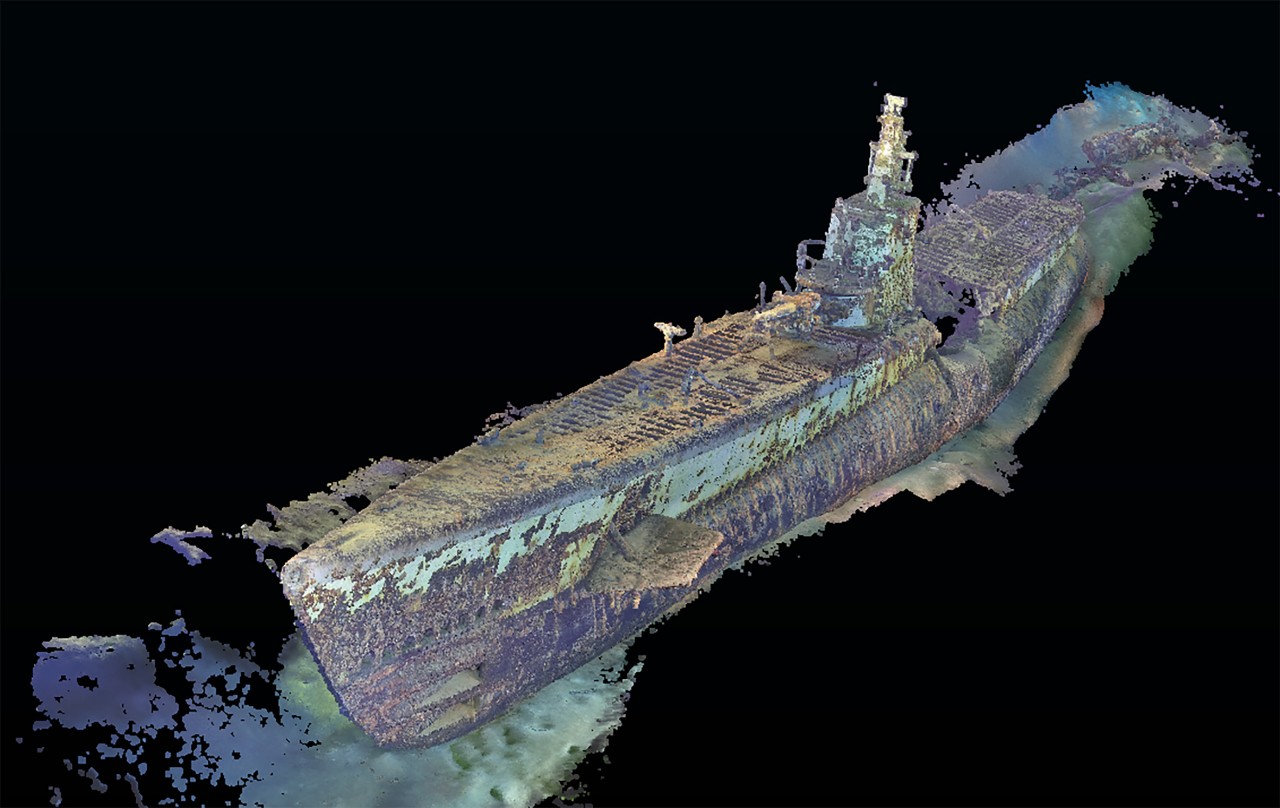

According to Japanese records, as CD-22 made its attack run, two torpedoes passed down its port side and one down its starboard side, indicating Harder had fired a down-the-throat shot at the oncoming escort ship, but missed. CD-22 then commenced a series of depth-charge runs with its Type 94 depth-charge throwers (it had 12, with 120 depth charges) with each charge set deeper than the last. The fifth salvo sank Harder, bringing a large amount of oil, pieces of cork, and wood to the surface.

Harder was presumed lost on 2 January 1945 and stricken from the Naval Register on 20 January 1945. All 79 men aboard Harder were lost. Harder was awarded a Presidential Unit Citation for its first five war patrols and six battle stars for its six war patrols. In postwar analysis, Harder was credited with sinking 16 ships totaling 54,002 tons (this does not include the warships).

Commander Samuel D. Dealey was awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor for the 5th war patrol and a posthumous Silver Star for the sixth war patrol. Lieutenant Samuel L. Logan, who had fleeted up to be executive officer on the 6th war patrol, was awarded a posthumous Silver Star (he had previously been awarded a Navy Cross for the rescue of the Navy pilot at Woleai).

Rear Admiral Christie nominated Dealey for the Medal of Honor as soon Harder did not return. Admiral Thomas Kinkaid, the commander of U.S. Seventh Fleet under General MacArthur, disapproved Dealey for the Medal of Honor on grounds that the Army Distinguished Service Cross awarded by MacArthur after the fifth war patrol was sufficient. There was already significant personal animosity between Christie and Kinkaid, and many in the submarine community blamed Christie for allowing Dealey to go on the last patrol. In December 1944, Kinkaid relieved Christie, who then returned to Washington, DC. Christie was subsequently able to go around Kinkaid and gain MacArthur’s backing for the Medal of Honor, which was presented to Dealey’s widow, Edwina, on 29 August 1945.

The destroyer escort Dealey (DE-1006), commissioned in 1953, was named in honor of Samuel Dealey. Dealey served until 1972, when it was transferred to the navy of Uruguay and ultimately scrapped in 1991.

The Medal of Honor citation for Commander Samuel Dealey reads as follows:

The President of the United States, in the name of Congress, takes pride in presenting the Medal of Honor (Posthumously) to Commander Samuel David Dealey, United States Navy, for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty as Commanding Officer of the U.S.S. Harder during her Fifth War Patrol in Japanese-controlled waters. Floodlighted by a bright moon and disclosed to an enemy destroyer escort which bore down with intent to attack, Commander Dealey quickly dived to periscope depth and waited for the pursuer to close range, then opened fire, sending the target and all aboard down in flames with his third torpedo. Plunging deep to avoid fierce depth charges, he again surfaced and, within nine minutes after sighting another destroyer, had sent the enemy down tail first with a hit directly amidships. Evading detection, he penetrated the confined waters off Tawi Tawi with the Japanese fleet base six miles away and scored death blows on two patrolling destroyers in quick succession. With his ship heeled over by concussion from the first exploding target and the second vessel nose-diving in a blinding detonation, he cleared the area at high speed. Sighted by a large hostile fleet on the following day, he swung his bow toward the lead destroyer for another “down the throat” shot, fired three bow tubes and promptly crash-dived to be terrifically rocked seconds later by the exploding ship as the Harder passed underneath. This remarkable record of five vital Japanese destroyers sunk in five short-range torpedo attacks attests the valiant fighting spirit of Commander Dealey and his indomitable command.

During the war, Commander Dealey was given credit for sinking six Japanese destroyers (one on the fourth patrol and five on the fifth) plus two frigates for a total of eight surface combatants. The actual total was four destroyers (one on the fourth patrol and three on the fifth) for a total six surface combatants. This is still the most warships sunk by a U.S. submarine commander in history. It may be the most of any submarine commander in any nation, as the closest I can find was U-9 under Otto Weddigen in World War I, which sank three armored cruisers and one protected cruiser in August and September 1914 (before the Royal Navy got wise to not stop to rescue survivors when the submarine was still in the area).

So from a historical accuracy standpoint, like many other combat awards, Dealey’s Medal of Honor citation has some fiction. However, the valor above and beyond the call of duty is completely accurate.

____________

Sources include: Naval History and Heritage Command Dictionary of American Fighting Ships (DANFS) for U.S. ships; combinedfleet.com for Japanese ships. Additional sources include the Naval Submarine League (navalsubleague.org) entry on Dealey; USNA Virtual Memorial Hall (usnamemorialhall.org); and On Eternal Patrol (oneternalpatrol.com). Also, Submarine! by Captain Edward L. Beach, USN, Signet Books: 1960, 88–104.