Operations in Bosnia and Herzegovina

The aircraft carrier George Washington (CVN-73) on patrol in the Adriatic Sea on 3 February 1996 as part of the NATO Operation Joint Endeavor. (National Archives and Records Administration [NARA], NAID: 6503284)

Contents

A map of the former Yugoslavia illustrating the six republics: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia. (Naval History and Heritage Command [NHHC])

The demise of the multiethnic Yugoslavia started in 1980 after the death of its Communist dictator, Josip Broz Tito. Under his regime, Tito had outlawed nationalism, and the six republics of Yugoslavia—Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia—were ruled under the slogan “Brotherhood and Unity.” Although Tito seemed successful at keeping the country united, deep-rooted nationalism based on economic inequalities and historical ethnic tensions flourished following his death as various would-be leaders began vying for power.

The state of Yugoslavia began crumbling on 25 June 1991, when Croatia and Slovenia declared independence. In response, the Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA) deployed to Slovenia and Croatia to stop the republics from breaking away. Although the JNA’s deployment to Slovenia was brief, the military campaign in Croatia was far more extensive due to the native Serb minority declaring independence, with the war claiming the lives of tens of thousands of civilians and resulting in hundreds of thousands being displaced.[1] By early 1992, the UN brokered a cease-fire and deployed a UN Protection Force (UNPROFOR) to Croatia in an attempt to stop the violence from spreading to the other republics. The pause in violence was short lived as another war broke out in Bosnia following a successful referendum vote for independence.

Of the six republics, Bosnia was the most ethnically diverse, with 43 percent of Bosnians identifying as Bosniak (Bosnian Muslims), 31 percent as Serb, and 17 percent as Croat.[2] This diversity played a role in the referendum vote as Bosnian Serbs generally wanted to align with Serbia and create the independent Republic of the Serbian People in Bosnia-Herzegovina, while Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats favored independence. On 5 April 1992, the Bosnian government declared independence. In response, Bosnian Serb separatists, supported by the JNA, began a violent assault on Sarajevo and villages around Bosnia and committed acts of ethnic cleansing to create a Serb republic. Bosnian Serb forces under General Radovan Mladic quickly laid siege to the Bosnian capital, Sarajevo. By the end of 1992, Bosnian Croat forces also decided to secede and join forces with the Croatian army in fighting against both Bosnian Serbs and the Bosnian army. With the evidence of images and accounts describing civilians being forced from their homes, starved, tortured, sexually assaulted, and killed based on their ethnic identity, it did not take long for the UN to call on its members, including the United States and its NATO allies, to stop the warring factions from committing further crimes against humanity. The United States met this request by deploying numerous naval vessels to the Adriatic and Mediterranean Sea and reinforcing its forces in the region.

U.S. troops stand at attention during a ceremony on 4 July 1994 at Camp Pleso in Zagreb, Croatia, where the U.S. Army, Air Force, and Navy treated UNPROFOR troops. (NHHC, 330-CFD-DF-ST-95-01571)

By 1992, as violence and human suffering engulfed the former Yugoslavia, the UN deployed forces to the region to provide much-needed humanitarian aid. During the conflict, roughly 40,000 UNPROFOR troops were deployed to either Croatia or Bosnia to promote and enforce peace. The first UNPROFOR troops arrived in Zagreb, Croatia in early 1992 to implement the cease-fire brokered by the UN. Another force deployed to Bosnia to deliver humanitarian assistance and establish UN safety zones for refugees.

As the violence continued and the UN searched for answers to bring relief to civilians, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 770 and directed all members to assist in delivering and providing humanitarian aid to the Bosnian population.[3] Shortly after, President George H. W. Bush ordered U.S. forces to undertake humanitarian airlifts and establish a temporary base in Zagreb to support this effort. This order initiated Operation Provide Promise, which lasted until January 1996 and became the longest-running humanitarian airlift operation performed by the Department of Defense at that time.[4] Throughout the operation, the Air Force, Army, and Navy assisted the UN by conducting airlifts, providing air cover for cargo planes, and establishing and staffing a field hospital for UNPROFOR troops.

In the spring of 1992, the United States began supporting UNPROFOR troops in distributing aid by landing five C-141s with food and medical supplies at the Sarajevo airport.[5] The initial plan was for international relief to land at the Sarajevo airport and be transported within the city or to other areas in Bosnia by UNPROFOR troops; however, Bosnian Serb forces advanced on Sarajevo, making such landings more dangerous. Tragedy struck the operation in September 1992 when an Italian cargo plane was shot down and the four crewmembers killed.[6] Complicating matters further, Bosnian Serb forces began blockading Bosniak villages and barring UN aid trucks from entering.[7] Determined to get aid into these enclaves, the United States shifted tactics and began airdropping food and medical supplies.

Although most airlifts were conducted by the Air Force, the Navy was tasked with conducting surveillance flights and providing air cover for cargo planes to avoid any American aircraft from being shot down. From February to April 1993, the Navy completed 375 sorties, deploying carrier-based F-14s, F/A-18s, A-6Es, EA-6Bs, E-2Cs, and S-3Bs.[8] Over almost four years and 12,000 sorties, the coalition dropped nearly 160,677 metric tons of aid to Sarajevo. The United States was responsible for more than 4,500 of the 12,000 sorties and roughly 63,000 metric tons of aid.[9]

In addition to dropping humanitarian aid, the United States supported the UN by establishing and staffing a 60-bed military field hospital at the UN base at Camp Pleso in Zagreb. The field hospital was responsible for providing medical care to the nearly 40,000 UNPROFOR troops. The care administered ranged from treatment of minor injuries and illnesses to severe landmine-related injuries. Although the primary focus was UNPROFOR troops, U.S. troops also provided medical aid to civilians impacted by the war. Every six months, the United States would rotate the Air Force, Army, or Navy unit staffing the hospital. In March 1994, the first naval unit was deployed to run the field hospital. For six months, the Navy’s Fleet Hospital 6 treated over 91,000 UNPROFOR soldiers and civilians.[10] Fleet Hospital 6 was relieved by roughly 230 naval doctors from Fleet Hospital 5 of Portsmouth, Virginia, which served as the last naval hospital unit at Camp Pleso during Operation Provide Promise.[11]

Although the majority of the aid airlifts were conducted by the Air Force, the Navy still played a critical role in Operation Provide Promise by providing logistical assistance and much-needed aerial surveillance. As the United States escalated the operations in Bosnia, the Navy took on an even larger role.

Captain Thomas R. Fedyzyn, commanding officer of the guided missile cruiser Normandy (CG-60), monitors the movements of a Bulgarian cargo ship as part of Operation Sharp Guard. The crew of Normandy boarded and searched the ship to ensure no illegal items were being transported to the warring factions, circa 1993. (NARA, 6502672)

In 1991, as the violence in Croatia surged, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 713, which established an arms embargo on weapons entering Yugoslavia.[12] The UN hoped that this would block weapons from falling into the hands of the warring factions and prevent the war from spreading. Even with the embargo in place, black market weapons continued to flood into Bosnia, Croatia, and Serbia from countries around the world, including Belarus, Bulgaria, Pakistan, Iran, Poland, and Russia.[13] Although some weapons reached the hands of the Bosnian army, the majority of weapons were supplied directly to the Bosnian Serb forces by the Serbian government, with the Bosnian Serbs quickly taking control of nearly 70 percent of Bosnia in a matter of weeks.[14]

The crimes against humanity committed during the initial assault by the Bosnian Serbs and the JNA resulted in the UN Security Council imposing economic sanctions against Serbia and Montenegro in May 1992 under UN Resolution 757 in an attempt to discourage them from further supplying the Bosnian Serbs.[15] Even with these resolutions in place, the warring factions continued to skirt the embargo and sanctions, resulting in the UN requesting support from NATO to monitor and enforce the embargo, thus initiating Operation Sharp Guard, which lasted from June 1993 till June 1996.

The United States responded to the UN’s request by deploying both naval vessels that could stop and search ships approaching the Adriatic Sea and naval aircraft that could patrol the waters and check for any ships attempting to evade the blockade. The U.S. Navy was tasked with patrolling two zones, the first along the Strait of Otranto, located between Italy and Albania, and the second along the coast of Montenegro, where the Serbian naval base of Kotor was located. Forces also had to pay particular attention to Croatia’s long coastline, as its geography made it easier for ships to evade the blockade and reach either mainland Croatia or Kotor. To prevent the embargo from being violated, the Navy deployed cruisers with the Aegis radar surveillance systems to serve as a link between the NATO surface ships and the maritime aircraft patrolling the seas, providing a clear picture of the situation and ensuring the blockade remained intact. In total, NATO forces conducted 13,325 sorties, challenged 74,192 ships, inspected 5,951 vessels, and escorted 1,480 ships to Italy for additional inspection.[16] Unfortunately, due to some of the command operations reports at this time remaining classified, it is difficult to definitively determine how many of the sorties were conducted solely by the U.S. Navy. However, based on the information available, we do know that the following ships were deployed to the region to support the Navy’s mission: America (CV-66), George Washington (CVN-73), Theodore Roosevelt (CVN-71), John F. Kennedy (CVA-67), Saratoga (CV-60), Mississippi (CGN-40), Dwight D. Eisenhower (CVN-69), and Normandy (CG-60). During their deployments, these carriers sailed with battle group ships that would stop, board, search, and, if needed, seize and escort vessels to Italy. For example, in 1993, when Hawes (FFG-53) was accompanying the carrier Theodore Roosevelt, the frigate challenged 310 vessels, boarded 30, and seized one vessel for further inspection.[17] In addition to maintaining carriers on station, the Navy also deployed submarines to monitor the shores of Montenegro and notify surface ships of any sorties by the Yugoslav navy.[18] In the first 30 months of the operation, Navy submarines provided two-thirds of NATO’s submarine coverage.[19]

As part of Operation Sharp Guard, the Navy deployed land- and carrier-based aircraft to conduct patrol and reconnaissance missions. Nearly two-thirds of the maritime patrol aircraft missions implemented during this operation were completed by U.S. Navy P-3 Orions, which were designed to patrol, detect, and destroy enemy submarines and cargo vessels.[20] The Navy also used EP-3s—based at Naval Air Station Sigonella, Italy—to carry out daily reconnaissance and collect signals intelligence on potential embargo violators in the Adriatic Sea. Additionally, carrier-based aircraft, including S-3 antisubmarine warfare aircraft, F/A-18 and F-14 fighter jets, and E-2C airborne early warning aircraft, also contributed to Operation Sharp Guard.[21] Naval aviators generally would fly six-hour missions, covering either the Montenegro coast or near the Otranto Strait checkpoint, with patrols over Montenegro occurring around the clock.[22] Attempts to evade the embargo occurred; however, the combination of air and sea power enabled the Navy and its NATO allies to stop these attempts and enforce the blockade.

An F-14A Tomcat launches from the aircraft carrier Theodore Roosevelt (CVN-71) on 1 April 1993 to enforce the no-fly zone as part of Operation Deny Flight. (NARA, 6483633)

Unfortunately, the economic sanctions and weapons embargo did little to stop the fighting and acts of ethnic cleansing. In another attempt to limit the violence on the ground, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 781 on 9 October 1992, which established a ban on military flights in the Bosnian airspace.[23] The warring parties blatantly ignored the no-fly zone, with NATO officials estimating that the belligerents violated the resolution at least 500 times in six months.[24] On 31 March 1993, under UN Resolution 816, the Security Council expanded the ban to cover all aircraft, including helicopters, and granted UN members permission to take military action to ensure compliance. This initiated Operation Deny Flight.[25]

Although NATO forces were granted enforcement capabilities, they struggled to stop helicopter flights due to difficulties in detecting low-flying aircraft and warring parties altering the helicopters to mirror UN and International Red Cross aircraft, with Bosnian Serbs painting their helicopters with red crosses and Bosnian Croat forces painting their helicopters to resemble UN aircraft.[26] Even if NATO intercepted and confirmed a warring party was using the helicopter, NATO forces were required to give a warning before shooting down the aircraft, thus allowing helicopters time to wait for the NATO aircraft to leave the area before taking off again and continuing on their missions moving troops, carrying military supplies, or attacking enemy and civilian targets. Although NATO forces struggled to curtail no-fly zone violations by with rotary-wing aircraft, they were able to decrease the number of flights conducted by fixed-wing aircraft.

Both the Navy and Marine Corps aviation components played a critical role in Operation Deny Flight.[27] Both land- and carrier-based aircraft were used, with many of the carriers providing operational support under Operation Sharp Guard also supplying the aircraft used by NATO for Operation Deny Flight. When Operation Deny Flight was first initiated, Theodore Roosevelt was stationed in the Adriatic to enforce the arms embargo and was immediately directed to utilize its F/A-18 Hornets, EA-6B Prowlers, and F-14 Tomcats.[28] In the first couple of months, the carrier’s Prowlers, designed for tactical electronic warfare such as jamming enemy radar, often provided “the only means to counter enemy air defenses.”[29] In August, Theodore Roosevelt was relieved by America, which deployed to the region with Airborne Command and Control Squadron (VAW) 123 “Screwtops.” The Screwtops were the second E-2C squadron in the Navy to conduct airborne early warning operations in Bosnia.[30] In September alone, the VAW-123 flew 76 sorties over roughly 226 hours.[31] Even as Navy carriers rotated in the Adriatic, each carrier continued to provide aircraft and contributed to the more than 13,500 sorties completed by the Navy and Marine Corps.[32] Naval aviators proved particularly important in providing air defense suppression, completing more than 70 percent of NATO’s air defense suppression sorties during the operation.[33]

In addition to enforcing the no-fly zone, the Navy and Marines also played a pivotal role in the search and rescue efforts of NATO aircraft and personnel. This service became critical in June 1995, when Bosnian Serbs shot down a U.S. Air Force pilot. On 2 June 1995, Captain Scott O’Grady was shot down by a Serbian SA-6 surface-to-air missile while conducting a routine air patrol mission. O’Grady evaded capture for six days by hiding in the forest while using his radio to call for help. On 8 June, NATO aviators made verbal contact with O’Grady, thrusting the Navy and Marines into an urgent rescue mission. The Navy ordered the 24th Marine Expeditionary Unit and Amphibious Squadron 8 aboard Kearsarge (LHD-3) to be ready to launch and, within four hours, 57 marines and 4 sailors were deployed as part of the rescue mission.[34] Shortly before 0700, the rescue team contacted O’Grady, who shot a smoke signal to mark his position. Two CH-53E Super Stallions landed, and within minutes, O’Grady was running from the tree line, with his 9-mm Beretta pistol in the air, toward the rescue team. He was quickly pulled onto one of the CH-53Es and began his journey to safety. While returning to Kearsarge, the marines and sailors came under fire by Bosnian Serb forces, but no injuries were reported.

Captain Scott O’Grady, USAF, talks to reporters on 10 June 1995 following his rescue from Bosnian Serb territory after his aircraft was shot down during Operation Deny Flight. (NARA, 6498130)

Bosnian Serb forces continued to escalate their attacks against NATO forces, UN peacekeepers, and thousands of innocent Bosnian civilians. Arguably the worst violence occurred in July 1995 at the UN safe area of Srebrenica, a small village where nearly 60,000 Bosniak refugees sought safety from ethnic cleansing. When the Bosnian Serb forces under General Mladic arrived, the outnumbered Dutch UN force agreed to hand over the village, with Bosnian Serb troops promising not to harm the refugees if the village disarmed.[35] This was a lie and the worst act of genocide in Europe since the Holocaust ensued. The Bosnian Serbs separated the women, children, and elderly from the men and young boys. The roughly 30,000 women, children, and elderly were moved to nearby towns, while an estimated 8,000 men and young boys were slaughtered.[36] The massacre was reported by the media, resulting in the UN authorizing NATO air strikes against Bosnian Serb military targets. The final straw occurred in August, when, after being warned by NATO to cease attacks on designated safe areas and remove all heavy weapons from the surrounding hills of Sarajevo, Bosnian Serb forces shelled a market and killed roughly 40 civilians.[37] NATO responded quickly under the leadership of Admiral Leighton Smith, USN, commander-in-chief of U.S. Naval Forces Europe and of NATO’s Allied Forces Southern Europe, by initiating NATO airstrikes.

Devastation in downtown Grbavica, a suburb of the capital Sarajevo, on 15 March 1996. (NARA, 6500701)

Operation Deny Flight was an important step in the efforts to stop the atrocities in Bosnia and was the first combat engagement in NATO history. Although there were more than 5,000 violations of the Bosnian airspace from November 1992 to July 1995, the operation allowed NATO forces to gain air superiority, which was paramount as NATO began conducting air strikes against Bosnian Serb military targets.[38]

Within two days of the market attack, NATO and the United States launched Operation Deliberate Force to coerce the Bosnian Serbs to withdraw heavy weapons from the exclusion zone around Sarajevo, reduce the threat to UN-designated safe areas, and comply with UN resolutions.[39]

Although the operation officially started on 30 August, NATO had already been preparing for air strikes by selecting an initial set of 56 military targets.[40] Fearful of the conflict growing and potentially requiring NATO ground troops, military leaders were determined to target only military equipment and use precision munitions to decrease the possibility of killing Bosnian Serb soldiers. Learning from Operation Deny Flight, officials also recognized a need for sound intelligence and surveillance to locate Bosnian Serb surface-to-air missiles and antiaircraft artillery. With this in mind, Admiral Smith ordered 350 coalition aircraft, including over 280 U.S. aircraft, to prepare for action.[41]

By 0200, 30 August, the first phase of Operation Deliberate Force commenced when roughly 40 suppression-of-enemy-air-defenses (SEAD) and strike aircraft, including 31 F/A-18C Hornets, 4 F-14 A Tomcats, and 2 EA-6Bs, launched from Theodore Roosevelt.[42] These aircraft were accompanied by additional EA-6Bs from the Aviano air base in Italy. Aviators were directed to strike 10 targets near Sarajevo.[43] The first part of Operation Deliberate Force focused on reducing Bosnian Serb’s integrated air defense system, including early warning radar sites, communication hubs, air defense command and control facilities, and known surface-to-air missile sites.[44] By the third day, NATO forces had completed 635 sorties, of which roughly 400 were launched from Theodore Roosevelt.[45]

U.S. Navy personnel at the Aviano Air Base load an EA-6B Prowler with AGM-88 HARM missiles in preparation for NATO airstrikes against Bosnian Serbs as part of Operation Deliberate Force on 12 September 1995. (NARA, 6498330)

Although NATO forces were making progress, they were ordered to cease all strike operations temporarily the request of the UN, which was conducting intense negotiations with Bosnian Serb leaders. During the pause in bombing, NATO continued reconnaissance missions to monitor Bosnian Serb movements.[46] Negotiations failed as General Mladic refused to accept the UN’s demands and even challenged the UN and the negotiators, including representatives from the United States, to meet his demands if they wanted peace. NATO officially restarted the bombings on 5 September and was determined to place the utmost pressure on the Bosnian Serb military and political leaders. On 10 September, the Navy launched 13 Tomahawk land-attack missiles (TLAMs) from Aegis guided-missile cruiser Normandy. These missiles targeted a radar installation near Banja Luka that was enabling Bosnian Serbs to monitor flights in the Adriatic, thus posing a threat to NATO aircraft.[47] The air strikes continued, and within days, NATO officials were running out of targets as most of the 56 pre-approved sites had been successfully bombed. On 14 September, NATO officials decided they needed a pause in the bombings to determine the impact of the operation. Six days later, Admiral Smith announced the mission was complete and that all goals of Operation Deliberate Force had been achieved, with NATO forces successfully hitting 97 percent of its targets.[48]

Throughout Operation Deliberate Force, the United States played a pivotal role in the air strikes against Bosnian Serb military installations, providing 127 aircraft and flying 2,087, or 60 percent, of the 3,535 sorties conducted by NATO.[49] During this operation, the U.S. military relied heavily on the Navy to launch cruise missiles and employ naval aviation assets to fly attack and surveillance missions. As previously mentioned, once NATO received approval to commence air strikes, the U.S. Navy was the first to respond with 40 strike and SEAD aircraft launching from Theodore Roosevelt. The Navy continued providing logistical and tactical support during the operation, supplying more than 20 percent of the U.S. 127 aircraft used, including 18 F/A-18Cs and 10 EA-6Bs.[50] The Navy also successfully launched 13 TLAMs into Bosnia, with 11 of the 13 landing within 30 feet of the intended target and rendering significant damage. Throughout the operation, naval aviators made their presence known by completing roughly 40 percent of the 2,087 sorties conducted by U.S. forces and conducting 56 percent of all SEAD missions in Operation Deliberate Force.[51]

The bombing campaign demonstrated to Bosnian Serbs, and their main backer, Serbia, that NATO was serious, and negotiations were the only option. The campaign against Bosnian Serb military assets had enabled the Bosnian army to regain 20 percent of the territory previously lost, meaning that the country was now split evenly. Facing a difficult reality, the Bosnian Serb president Radovan Karadzic and General Mladic agreed to the UN demands and removed heavy weaponry from the exclusion zone around Sarajevo.

By October 1995, with the harsh Bosnian winter fast approaching and the future of the war looking bleak, Bosnian Serb forces, under immense pressure from the international community, agreed to a cease-fire and to discuss a peace agreement.

(Standing, left to right) Prime Minister Felipe Gonzalez of Spain, President Bill Clinton, President Jacques Chirac of France, Chancellor Helmut Kohl of Germany, Prime Minister John Major of the United Kingdom, and Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin of Russia watch as President Slobodan Milosevic of Serbia, President Alija Izetbegović of Bosnia, and President of Fanjo Tudjman of Croatia sign the Dayton Peace Accord in Paris on 14 December 1995. (NARA, 7595486)

The Clinton administration selected Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio, as the meeting place for the historic summit. The negotiations included Serbian president Slobodan Milosevic (representing Bosnian Serbs), Bosnian president Alija Izatbegovic (representing Bosniaks), and Croatian president Franjo Tudjman (representing Bosnian Croats). The leaders reached a compromise after 21 days of negotiations and agreed to configure Bosnia into two entities, the Republika Srpska, which controlled 49 percent of the country, and the Bosnian Croat Federation, which controlled 51 percent of the country. On 14 December 1995, the Dayton Peace Accords officially went into effect, and a NATO implementation force (IFOR) of roughly 60,000 troops, including 20,000 U.S. personnel, deployed to Bosnia to enforce the peace agreement and oversee the transfer of territory between the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Republika Srpska.[52] During the IFOR mission, the Navy supported NATO by continuing to enforce the naval embargo and providing aircraft that monitored the transfer of territory and the movements of the former warring factions. The IFOR mission ended in September 1996 after the first election was held and the command was redesignated a stabilization force (SFOR). SFOR was authorized in December 1996 and lasted until 2004. During that time, NATO forces, including a smaller U.S. troop contingent, supported efforts to prevent hostilities, assisted those returning to their homes, and created a safer environment through a demining program. Both IFOR and SFOR were critical in enforcing and promoting peace within Bosnia and helping the country move forward.

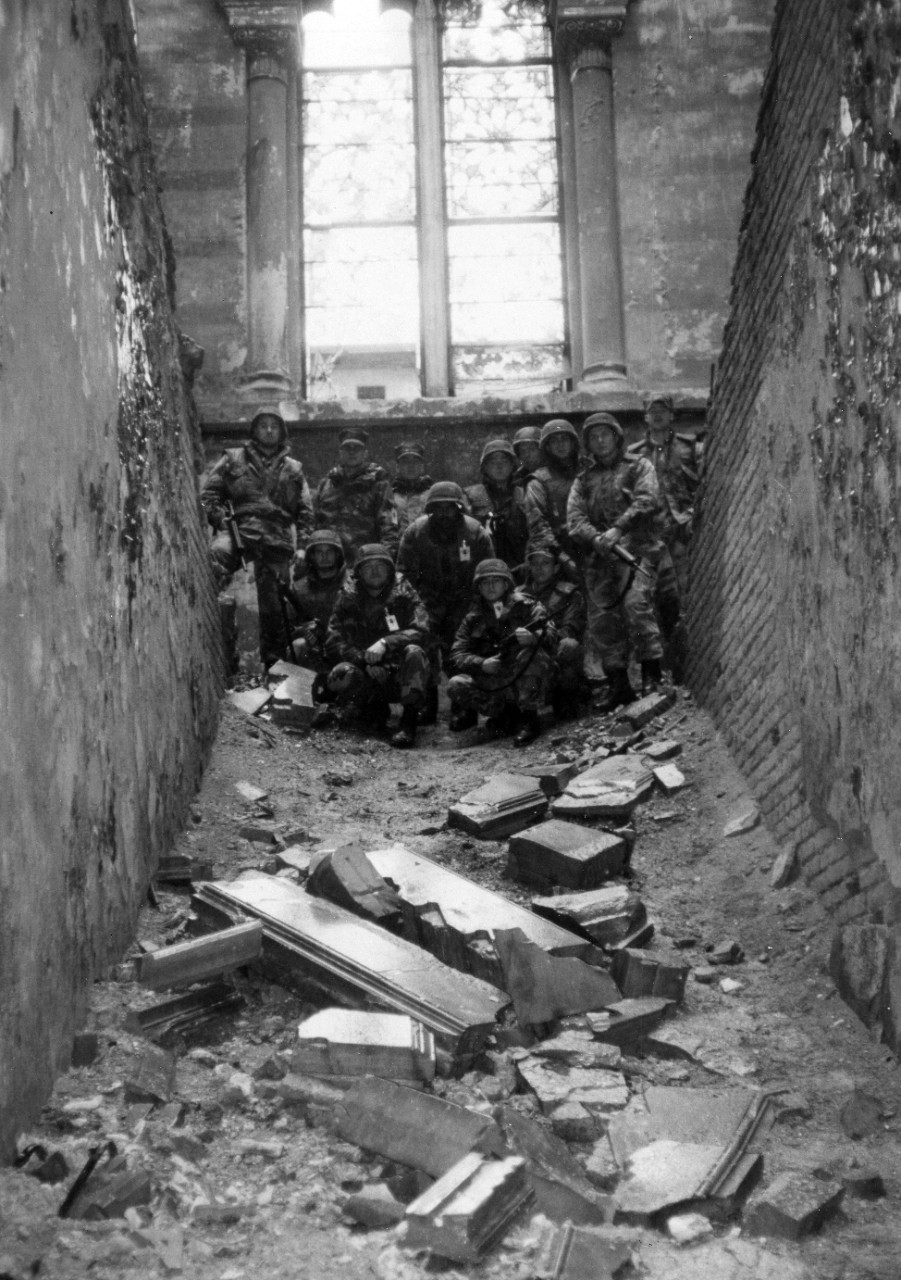

Seabees deployed in Sarajevo in support of the IFOR mission stand in a bombed-out church in February 1996. Seabees assisted in building temporary U.S. military bases housing U.S. IFOR troops and in constructing critical infrastructure destroyed during the war. (NHHC, UA 475.17)

Today, the Dayton Accords are still the foundation of the Bosnian constitution. Although the country continues to grapple with the crimes committed during the war, the peace agreement has endured, and large-scale violence has been avoided. The United States played a pivotal role in ending the civil war and brokering a peace agreement by having its armed forces enforce the UN-mandated humanitarian operation, weapons embargo, no-fly zone, and air strikes. Navy personnel were front and center in these operations, with sailors stopping and searching ships attempting to evade the blockade and aviators conducting hundreds of sorties to enforce the no-fly zone and strike Bosnian Serb forces violating UN resolutions. The combined efforts by the Navy, Army, Air Force, Marine Corps, and other NATO allies were not only critical in bringing an end to the violence in Bosnia but also in paving the way for future joint operations in the Global War Against Terrorism.

—Jacqueline Evans, NHHC Communication and Outreach Division

For additional information on the overall breakup of Yugoslavia:

Office of the Historian. “The Break-up of Yugoslavia, 1990-1992.” U.S. Department of State, accessed on 7 May 2024.

“The Dissolution of Yugoslavia.” Clinton Presidential Library, accessed on 7 May 2024.

For additional information on the genocide at Srebrenica:

International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunal. “Srebrenica: Timeline of Genocide.” United Nations, accessed on 10 May 2024.

****

[1] The Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA) was originally composed of individuals representing all six republics in Yugoslavia. However, as independence movements gain traction, soldiers began leaving the JNA and joining military factions within their specific republic. This in turn meant that most of the soldiers in the JNA were ethnic Serbs and sympathetic to the Serbian cause. Source: Michael O. Beale, “Bombs over Bosnia: Role of Airpower in Bosnia-Herzegovina” (master’s thesis, School of Advanced Airpower Studies, 1997), 4.

[2] Office of European Analysis, Bosnia-Herzegovina: On the Edge of the Abyss (Washington, DC: Central Intelligence Agency, 19 December 1991); Bosnian Muslims are referred to as Bosniaks.

[3] UN Security Council, Resolution 770, Bosnia and Herzegovina Situation, S/RES/770, (13 August 1992).

[4] “1992-1996 –Yugoslavia (Operation Provide Promise),” Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC), accessed 28 April 2024.

[5] A. Martin Lidy, David Arthur, James Kunder, and Samuel H. Packer, “Bosnian Air Drop Study,” Institute for Defense Analyses, 01 August 1999, 5.

[6] Blaine Harden, “Missile Hit Aid Plane, Initial Report Shows,” Washington Post, 16 September 1992.

[7] Daniel L. Haulman, “Provide Promise,” Air Mobility Command Museum, accessed 22 April 2024.

[8] Den Simmons, Phillip Gould, Verena Vomastic, and Philip Walsh, “Air Operations over Bosnia,” U.S. Naval Institute, May 1997.

[9] “USAF Humanitarian Efforts in Bosnia-Herzegovina,” National Museum of the United States Air Force, accessed 22 April 2024.

[10] André B. Sobocinski, “Remembering Navy Medicine in the Balkan Crisis,” Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, 28 June 2019.

[11] Kerry Derochi, “Healing the Peacekeepers a Portsmouth Medical Team Aids U.N. Troops Caught Up in Yugoslavia’s Age Old Hatreds,” Virginia Pilot, 10 September 1994.

[12] UN Security Council, Resolution 713, Yugoslavia—Political Conditions, S/RES/713, (25 September 1991).

[13] Office of Resources, Trade, and Technology, Croatia: Using the Gray Market to Beat UN Embargo (Washington, DC: Central Intelligence Agency, May 1995); Robert Cohen, “Arms Trafficking to Bosnia Goes on Despite Embargo,” New York Times, 5 November 1994.

[14] R. Cody Phillips, Bosnia-Herzegovina: The U.S. Army’s Role in Peace Enforcements Operations, 1995–2004 (Washington DC: Center of Military History, 2005), 11.

[15] UN Security Council, Resolution 757, Former Yugoslavia Situation, S/RES/757, (30 May 1992).

[16] Thomas Hone, “A History of the U.S. Sixth Fleet” (unpublished manuscript, 2018), Microsoft Word file.

[17] Commanding Officer USS Hawes (FFG-53), USS Hawes (FFG-53) Command Operation Report 1993 (Washington DC: NHHC, 1994).

[18] Sarandis Papadopoulos, “The U.S. Navy’s Contribution to Operation Sharp Guard,” in You Cannot Surge Trust (Washington, DC: NHHC, 2013), 92.

[19] Papadopoulos, “The U.S. Navy’s Contribution to Operation Sharp Guard,” 92.

[20] Papadopoulos, “The U.S. Navy’s Contribution to Operation Sharp Guard,” 91.

[21] Simmons et al., “Air Operations over Bosnia.”

[22] Papadopoulos, “The U.S. Navy’s Contribution to Operation Sharp Guard,” 91.

[23] UN Security Council, Resolution 781, Bosnia and Herzegovina Situation, S/RES/781, (9 October 1992).

[24] Eric Lockwood, “USS Theodore Roosevelt Kicks off Operation Deny Flight,” The Sextant (Blog), NHHC, 12 April 2015.

[25] UN Security Council, Resolution 816, Bosnia and Herzegovina Situation, S/RES/816, (31 March 1993).

[26] Beale, “Bombs over Bosnia,” 31.

[27] Simmons et al., “Air Operations over Bosnia.”

[28] Lockwood, “USS Theodore Roosevelt.”

[29] Lockwood, “USS Theodore Roosevelt.”

[30] Commanding Officer, Carrier Airborne Early Warning Squadron 123, Command Operation Report VAW 123 1993 (Washington DC: NHHC, 1994, 4).

[31] Commanding Officer, Carrier Airborne Early Warning Squadron 123, Command Operation Report, NHHC, 5.

[32] Simmons et al., “Air Operations over Bosnia.”

[33] Simmons et al., “Air Operations over Bosnia.”

[34] Martin R. Berndt and Michael C. Jordan, “The Recovery of Basher 52,” U.S. Naval Institute, November 1995.

[35] Ivo H. Daalder, “Decision to Intervene: How the War in Bosnia Ended,” Brookings Institute, 1 December 1998.

[36] “Srebrenica: Timeline of Genocide,” International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals (IRMCT), accessed 7 May 2024.

[37] Robert C. Owen, Deliberate Force: A Case Study in Effective Air Campaigning: Final Report of the Air University Balkans Air Campaign Study (Maxwell Air Force Base, AL: Air University Press, 1999), 29.

[38] Beale, “Bombs over Bosnia,” 79.

[39] Owen, Deliberate Force: A Case Study, 44.

[40] Beale, “Bombs over Bosnia,” 59.

[41] Owen, Deliberate Force: A Case Study, 133.

[42] “1990 –1999: From the Sea,” NHHC, 13 September 2019.

[43] Owen, Deliberate Force: A Case Study, 311.

[44] Beale, “Bombs over Bosnia,” 57.

[45] Owen, Deliberate Force: A Case Study, 144; “1990–1999: From the Sea,” NHHC.

[46] Owen, Deliberate Force: A Case Study, 146.

[47] John A. Tirpak, “Deliberate Force,” Air and Space Forces Magazine, 1 October 1997.

[48] Tirpak, “Deliberate Force.”

[49] Tirpak, “Deliberate Force.”

[50] Tirpak, “Deliberate Force.”

[51] Owen, Deliberate Force: A Case Study, 335 and 346.

[52] Phillips, Bosnia-Herzegovina: The U.S. Army’s Role, 1.