Welcome to Navy History Matters—our biweekly compilation of articles, commentaries, and blogs related to history and heritage. Every other week, we’ll gather the top-interest items from a variety of media and social media sources that link to related content at NHHC’s website, your authoritative source for Navy history.

Compiled by Brent A. Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command Communication and Outreach Division

Battle of Saipan@80

Following intensive naval gunfire and bombing by carrier-based aircraft, Task Force 52 landed Marines of the 2nd and 4th Divisions on Saipan, June 15, 1944. The island was the first relatively large and heavily defended land mass in the Central Pacific to be assaulted by U.S. amphibious forces. Just before dawn on the opening day of operations, the Marines were served a hearty breakfast, and then it was time to board the amphibian tractors. Fifty-six of these vehicles proceeded in lines of four toward the eight designated landing beaches. Tens of thousands of Japanese personnel, with artillery rounds at the ready, held their fire as the amtracs traversed the reefs and arrived in the lagoon. Then, with a barrage of Japanese rounds, it became clear that the preparatory bombardment of shoreline defenses had not done enough to weaken enemy defenses. In addition, the Japanese were hidden well in Saipan’s topography, which featured high ground within range of the lagoon and reefs—a natural obstacle for U.S. forces and a focal point for Japanese fire. Deadly complications besieged American forces all at once. The intensity of the enemy’s defense resulted in some chaos as Marines tried to get a footing on shore, and the sheer number of U.S. troops storming the beach was an easy target for Japanese mortars and other projectiles. Nevertheless, the Marines managed to get to dry ground before the projected timeline had passed. Then came another obstacle. The amphibian tractors were not functioning as planned. Their armor was not heavy enough to withstand the barrage of Japanese artillery, and their agility on the rough terrain proved less than optimal. Marines scattered in several directions as hilltop snipers tried to pick them off one by one. Eventually, the Americans reestablished order and proceeded with the assault.

The Japanese resistance was far greater than anticipated because intelligence reports had underestimated Japanese troop levels. U.S. forces expected there to be about 31,000 enemy troops, but in reality there were about twice that many. For at least a month, the Japanese had been fortifying the island and bolstering its forces as well. During the first day of the assault, American casualties were high, with as many as 3,500 in the first 24 hours, despite having 20,000 troops on shore by sunset with more on the way. Reinforcements could not come quickly enough as the Japanese defense doubled down and changed tactics by deploying tanks and infantry in the darkness of night. Conditions improved the following day when a new group of battleships arrived to bombard the coast. In response to difficulties on the ground, U.S. forces postponed the invasion of Guam and the operation’s reserve, the Army’s 27th Infantry Division, was called in to assist the Marines.

The unexpected difficulties on the beaches prompted the Fifth Fleet commander, Adm. Raymond Spruance, to commit more ships to the operation. Spruance had good reason to worry about the beachheads, although they appeared to be secured by the second day of the battle. “The [Japanese] are coming after us,” Spruance said, and they were bringing with them 28 destroyers, 5 battleships, 11 heavy cruisers, 2 light cruisers, and 9 carriers with somewhere near 500 aircraft. The resulting engagement, Battle of the Philippine Sea (June 19–20), was a decisive victory for the Allies that nearly eliminated the Japanese ability to wage war by air. Notably, during the operation known as “The Great Marianas Turkey Shoot,” the U.S. destroyed nearly 600 enemy aircraft, sank two enemy fleet carriers, a light carrier, and two oilers, killing nearly 3,000 of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s pilots and sailors.

After the Battle of the Philippine Sea was over, U.S. forces turned the main effort back to Saipan, where reinforcements and materiel were still needed as the battle raged on. USS Sheridan (APA-51) was among the first of the ships to return to Saipan from the Philippine Sea. For days, Sailors witnessed the action on shore from the attack transport’s decks. The fighting was easier to decipher at dusk when the tracers came out, according to Lt. (j.g.) Harris Martin. “We could see some of our landing craft being hit by Japanese artillery, and we watched Japanese tanks as they counterattacked from the low hills.” When the island was finally declared secure on July 9, the work of processing prisoners of war, both civilian and military, began. In addition, Navy civil engineers (Seabees) began to plan for an internment camp and ordered the construction of shelters and other facilities.

During the Battle of Saipan, tens of thousands of Japanese troops were killed, and more than 1,700 were captured. Particularly shocking were the extensive civilian casualties, estimated to be as high as 22,000. Civilians, as well as Japanese military personnel, reportedly opted to commit suicide by jumping off cliffs rather than be captured. The Americans suffered greatly as well, with 26,000 casualties, of which 5,000 were killed in action. However, the American victory on Saipan was decisive. Japan’s National Defense Zone, demarcated by a line that the Japanese had deemed essential to hold in the effort to stave off a U.S. invasion, had been blown open. Japan’s access to scarce resources in Southeast Asia was now compromised, and the Caroline and Palau islands now appeared to be ready for the taking. With Saipan’s airfields soon to be operational (as well as those of Tinian and Guam, which the Americans would capture a short time later) and with Japanese airpower having been all but eliminated in the Battle of the Philippine Sea, there was little protection for the home islands from Allied aerial bombardment.

Elizabeth Reynard, Virginia Gildersleeve, and the Birth of the WAVES

Lt. Elizabeth Reynard was second in command of the WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service) during World War II. She and her partner, Virginia Gildersleeve, the dean of Barnard College, laid the foundation for the Women's Reserve. Gildersleeve led a women's advisory council tasked with assisting the Navy in establishing and administering a women's reserve. The council consisted of leaders of the nation’s most prominent women’s colleges.

In early 1942, Reynard, a former English professor at Barnard College, was selected to be a special assistant to the chief of the Bureau of Naval Personnel. Her task was to help the Navy develop a training plan for the new women's branch of the U.S. Naval Reserve. She visited numerous naval installations gathering information on what wartime jobs needed to be filled and how women might be incorporated into the positions. Additionally, she visited several U.S. universities to find locations for training schools for the new recruits.

In 1943, Reynard became the special assistant to the commanding officer at the U.S. Naval Training School (WR), Bronx, New York. Known as USS Hunter, this enlisted training facility, or boot camp, provided indoctrination training for nearly 86,000 WAVES. In 1944, after being promoted to lieutenant commander, Reynard became commandant of seamen at Hunter. She directed Hunter’s six-week training program, wherein she instructed recruits on naval traditions and tactics. She left active-duty naval service in October 1945 at the rank of lieutenant commander.

For more on Reynard and Gildersleeve’s role in the foundation of the Women’s Reserve, read a new blog, “Elizabeth Reynard, Virginia Gildersleeve, and the Birth of the WAVES,” by Communication and Outreach Division’s Wendy Arevalo at The Sextant.

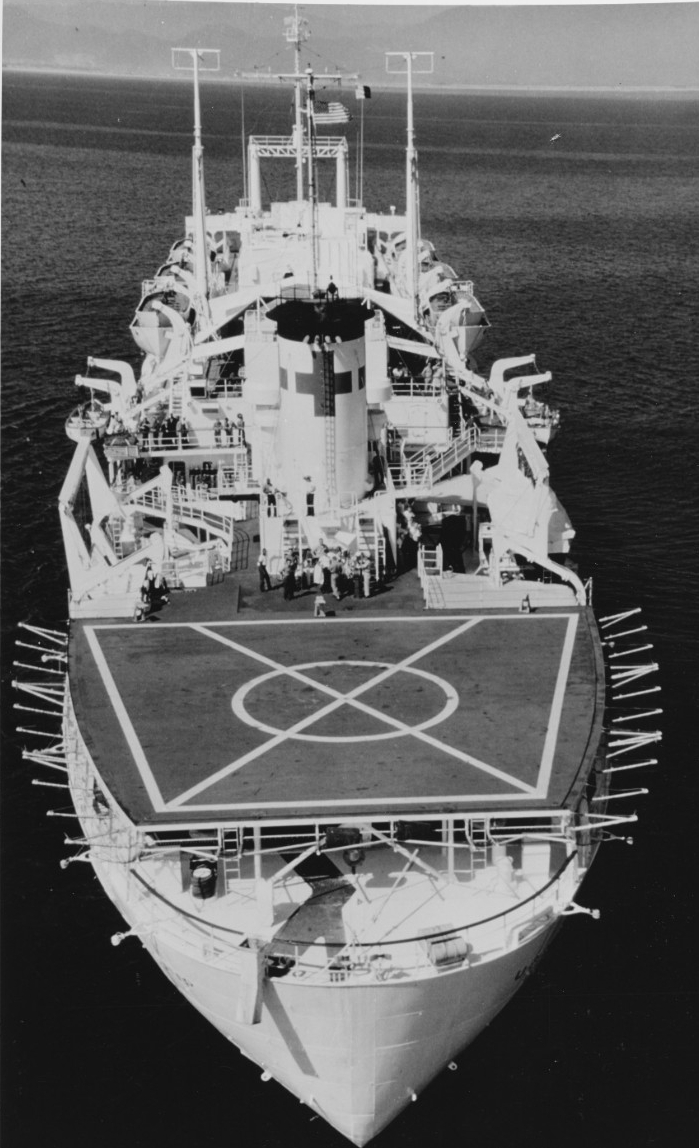

First American Hospital Ship off Vietnam: “Angel of the Orient”

On June 16, 1965, the U.S. Navy scheduled the reactivation of USS Repose (AH-16), which would be the first American hospital ship active during the Vietnam War. After the ship was reactivated and towed to various shipyards for repairs in the Pacific Northwest, Repose was recommissioned on Oct. 16, 1965, at San Francisco’s Hunters Point Naval Shipyard with Capt. Eugene H. Maher in command and Capt. Paul R. Engle as the senior medical officer. Repose departed San Francisco on Jan. 3, 1966, arriving at Pearl Harbor six days later for underway training. It then set course for Subic Bay in the Philippines, arriving on Feb. 3 to take on supplies and conduct repairs. Steaming on Valentine’s Day 1966 for Vietnam, Repose arrived two days later and commenced medical support off Chu Lai Air Base. Living up to its nickname, “Angel of the Orient,” Repose was permanently deployed to Southeast Asia until it departed Vietnam on March 14, 1970, when it was decommissioned and placed in reserve. During its extended stay in support of American operations in Vietnam, the 741-bed floating hospital ship treated more than 9,000 battle casualties and admitted more than 24,000 for inpatient care. Repose earned nine battle stars for its Vietnam service.

The ship was no stranger to the combat zone. Commissioned in the waning days of World War II, Repose was deployed to Shanghai, China, where it operated as a base hospital until October 1946. Afterwards, it was placed in reserve until the Korean War broke out in June 1950. With a desperate need for hospital ships, Repose was transferred to San Francisco and ordered activated at the earliest possible date. It steamed with a civilian crew for Yokohama, Japan, on Sept. 2, 1950, and arrived two weeks later. There, a Navy crew embarked, and the next day it set course for Pusan, Korea, arriving on Sept. 20. Repose remained off Pusan as a station hospital through Oct. 26, then departed for Yokohama with 189 patients. Returning to Korean waters on Nov. 13, Repose served at Inchon, Chinnampo, and Pusan before transporting 301 patients back to Yokohama. After undergoing availability repairs, Repose provided hospital services between Korean and Japanese ports throughout the rest of the year.

Following overhaul and installation of a helicopter platform, Repose returned to Inchon Harbor on June 24, 1952, where it began taking patients the same day. About a month later, Repose was joined by its sister ship USS Haven (AH-12) during increased Chinese involvement and as the air war over Korea intensified. Following a period of patient transfers between Korea and Japan, Repose returned to the U.S. West Coast where it underwent repairs. After work was completed and for the remainder of the Korean War, the ship took up station at Inchon. Repose earned nine battle stars for its Korean service.

Throughout history, vessels have been assigned to care for the sick and wounded when wars have been fought or humanitarian disasters occur. As early as 1803–04, during the Barbary Wars, Commodore Edward Preble designated the captured ketch Intrepid as a ship with hospital duties. The threat of yellow fever in 1859, an epidemic brought on by Sailors returning from foreign ports, instigated the first floating hospital in America. The infected Sailors were initially turned away at shore hospitals, so it was necessary to find a place to treat them. A New York physician, Dr. William Adison, who had recently returned from England where he studied in the floating hospital ship Caledonian, suggested a similar vessel. When his idea was accepted, port authorities voted to purchase the steamer Falcon. The engines were removed, the deck housed over, other necessary facilities installed, and various changes were made. Fittingly enough, the name was changed to Florence Nightingale, and a number of patients were cared for aboard it.

During the Civil War, captured sidewheel steamer Red Rover was the U.S. Navy’s first hospital ship. After Union gunboat Mound City captured the vessel from the Confederates, it was almost immediately prepared as a floating hospital for the casualties of the North. Red Rover had a crew of 12 officers and 35 men, exclusive of the 30 surgeons and nurses aboard. Not all of the nurses aboard were male. Four Sisters of the Holy Cross eventually came aboard and were joined later by several other sisters. Unknowingly at the time, this small group proved to be the pioneers of the Navy Nurse Corps that would be organized some 50 years later. During the war, Red Rover was kept busy with its patients, carrying medical supplies, ice, and provisions to the ships of the Western Rivers Fleet before it was removed from service following the war.

Navy hospital ships have come a long way since Red Rover. Today, the Navy has two active hospital ships that are under the Military Sealift Command, USNS Mercy (T-AH 19) and USNS Comfort (T-AH 20). They provide mobile, acute surgical medical facilities afloat when called upon to the U.S. military, and hospital services to support U.S. disaster relief and humanitarian operations worldwide. Both are 1,000-bed hospital ships with one (Comfort) homeported on the U.S. East Coast at Norfolk, Virginia, and the other (Mercy) on the U.S. West Coast at San Diego.

Today in Naval History—First Naval Battle of the American Revolution

On June 11, 1775, local militia, under the command of Col. Benjamin Foster, attempted to capture the commander of HMS Margaretta, Capt. James Moore, and a British loyalist, Ichabod Jones, while they were attending church at Machias, Maine (then part of Massachusetts). However, Moore managed to make his way back to his ship while Jones escaped into the woods. The two were in town trying to broker a deal with the locals to trade provisions they had on Jones’s merchant ships in exchange for lumber that was desperately needed to build barracks for arriving British troops. At this point, the American Revolution had already begun, with the Battles of Lexington and Concord fought on April 19 resulting in the first American victory and an outpouring of militia support for the anti-British cause. Previously, citizens of Machias voted against the transaction, not wanting to aid the British. As a consequence of the vote, Margaretta, which was there to provide security for the merchant ships, moved within firing distance of the town. The British move of intimidation infuriated the citizens of Machias.

After the attempt to capture the British captain and the loyalist failed, the following day, townspeople armed with muskets, pitchforks, and axes seized one of the merchant ships, Falmouth Packet, and armed it alongside a second ship, Unity, under the command of Jeremiah O’Brien, a local captain. The captured merchant ship was armed with bags of pewter plates, spoons, and mugs for ammunition while Unity was manned with the local militia. As Margaretta tried to escape by heading out toward the open sea, inept seamanship caused it to lose its gaff and boom, which made the vessel difficult to sail. The crew had to use the other merchant vessel for makeshift replacements. Then, it had to fix the rigging on Margaretta, which had been previously damaged by rough weather. This gave O’Brien’s sloop plenty of time to catch up with Margaretta and ram into its side. “To your feet lads. The schooner is ours. Follow me. Board,” said O’Brien. Twenty men, previously selected and armed with pitchforks, clambered over the rails. Shooting and hand-to-hand combat eventually commenced in the bloody struggle. When Margaretta’s captain attempted to throw several grenades onto Unity in an attempt to kill O’Brien, he was shot in the chest. Moore died a few days later from his wounds. With their captain down, the crew of Margaretta quickly surrendered. O’Brien personally hauled down the British ensign in triumph, and the captured British crew was turned over to the Massachusetts Provincial Congress.

The Battle of Machias has the distinction of being the first naval battle of the American Revolution. Machias patriots went on to capture numerous British vessels during the war, and many became part of the Continental Navy’s inventory. Machias was later targeted for invasion by the British in 1777, but the mission was a complete failure. O’Brien served with distinction throughout the war. He captained six privateers at sea between 1775 and 1781, and during his only time ashore, he led a company of militia defending against British-inspired hostile Indians. He has had five U.S. Navy vessels named after him. One of his namesake ships, SS Jerimiah O’Brien was launched in 1943 and participated in the 1944 invasion of Normandy. It is a National Historic Landmark and is permanently moored at Pier 45, at the foot of Taylor St., in San Francisco.