Welcome to Navy History Matters—our biweekly compilation of articles, commentaries, and blogs related to history and heritage. Every other week, we’ll gather the top-interest items from a variety of media and social media sources that link to related content at NHHC’s website, your authoritative source for Navy history.

Compiled by Brent A. Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command Communication and Outreach Division

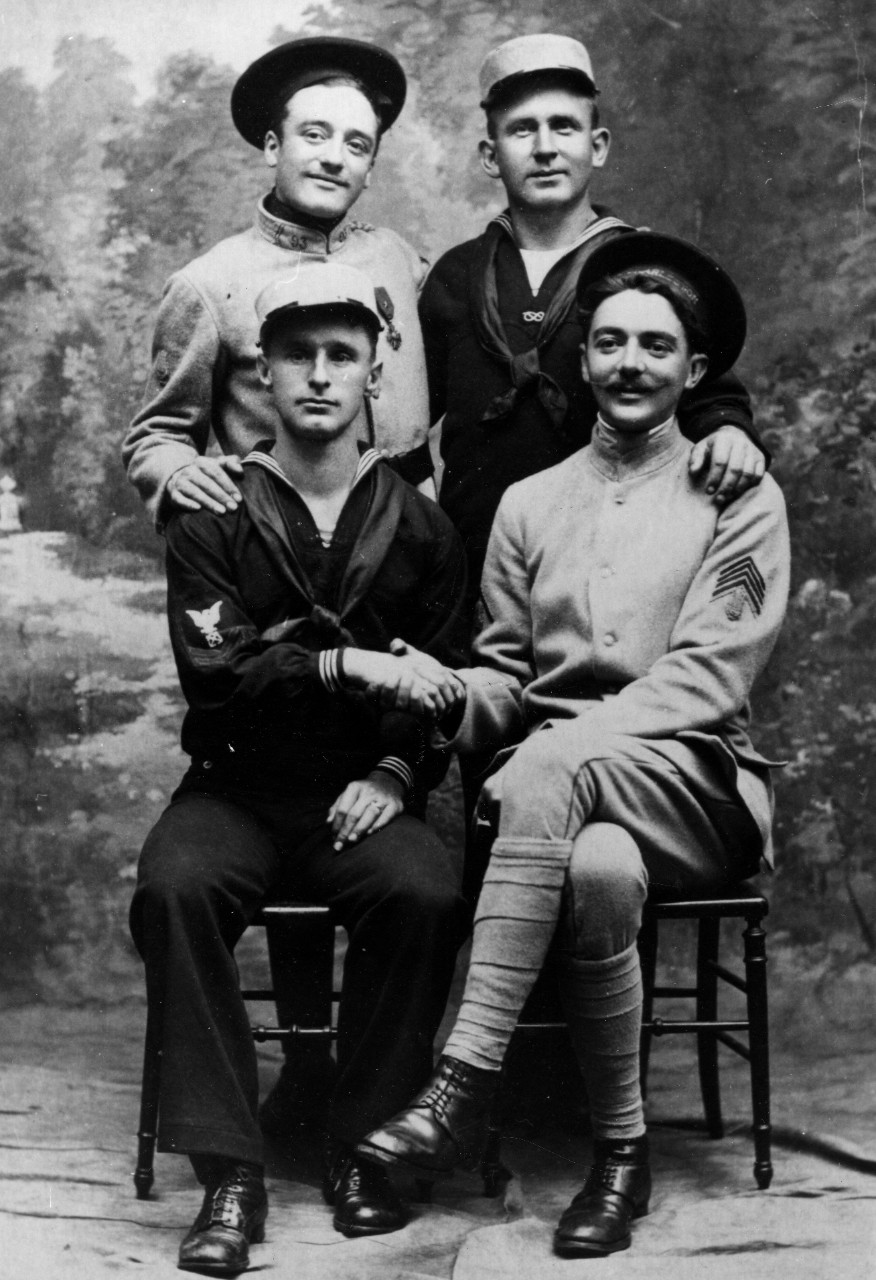

First U.S. Troops Arrive in France

On June 26, 1917, the first convoy transporting troops of the American Expeditionary Force began arriving in Saint-Nazaire, France, only two and a half months after the U.S. declared war on Germany. Their arrival (14,000 total, including 2,700 Marines) surprised Germany and provided a huge morale boast for the allies. The transport of that many troops in such a short period of time was an astonishing feat in 1917. For more than 100 years, the centerpiece of America’s defense policy revolved around defending the Western Hemisphere from European intrusions. When the United States declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917, even the most recent U.S. war plans emphasized defending the Caribbean against the Central Powers (Imperial Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire). A major troop movement to Europe had not been initially planned by the United States.

The Germans, above all, did not expect American troops to arrive so early in such significant numbers. Four months before the United States entered World War I, Kaiser Wilhelm II had met with his most trusted military advisors to consider the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare, which had been curtailed one year earlier due in large part to American pressure. The German policymakers believed that resuming U-boat attacks on neutral and allied shipping would cripple Great Britain and end the war in Germany’s favor. However, a likely consequence of that decision would be the United States’ entry into the conflict. Adm. Henning von Holtzendorff, chief of the German Imperial Admiralty staff and a leading proponent of unrestricted submarine warfare, argued that if the Kaiser released the U-boats, “England would be defeated within six months, at the most, before a single American had set foot on the continent.” He claimed that the United States offered no real threat to the Central Powers. “Money as well as words will be hurled at us and military developments will come either not at all or too late to have an effect.” The Kaiser agreed and ordered the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare on Feb. 1, 1917. Warned by telegram from the German ambassador in Washington that the action would likely lead to war with the United States, Wilhelm responded, “That is irrelevant.”

The Kaiser’s action and the subsequent attacks on American shipping did, in fact, lead to American involvement in the European war. However, the question remained as to how the United States could contribute to the war effort. Clearly, troops, materiel, and ships were essential, but also important was a morale boast for the allies who were on the brink of defeat. By early May 1917, the Franco-British Nivelle offensive failed to achieve its strategic objectives, with French soldiers walking away en masse from the frontlines (27,000 deserted). In addition, merchant shipping losses due to the resumed German U-boat campaign caused severe shortages and nearly brought Great Britain to its knees. In eastern Europe, revolutionaries overthrew the Russian Tsar and allied fronts in Russia and Romania were on the brink of collapse. With the allies in desperate need of assistance, a French delegation including former French Prime Minister René Viviani and former French army chief of staff Marshall Joseph Joffre visited the United States. They requested that the Americans send troops to France as soon as possible. They claimed that the arrival of this force, even if it was small, would boost allied spirits considerably. American dignitaries agreed to dispatch a force of Soldiers and Marines and transport them to France in American vessels. The War Department tapped Gen. John Pershing to make preparations for the arrival of the U.S. contingent and sent him to France. As part of the preparations for war, Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels named Rear Adm. Albert Gleaves as the commander of convoy operations. Gleaves went to New York City to prepare for the unprecedented operation.

However, Gleaves’s task was daunting. Only three commissioned Navy vessels were capable of transporting troops at the time—USS Hancock and USS Henderson, and the seized German auxiliary cruiser SMS Prinz Eitel Friedrich, renamed USS DeKalb. Ocean liners and merchant vessels were scraped together to carry the troops, and Gleaves ensured that they were armed, seaworthy, and staffed with naval personnel. Of the 13 vessels that transported troops, three were the commissioned Navy vessels, two were ocean liners from the United Fruit Company, two were mail carriers, and six were merchant vessels or ocean liners from several shipping companies. Workers labored around the clock to arm the commercial vessels for defense and outfitted them to carry troops. Four cruisers, 13 destroyers, three armed colliers, and two armed yachts would escort the improvised troopships to the western coast of France. They would steam in four separate groups.

At daybreak on June 14, the first convoy group, led by Gleaves in his flagship, armored cruiser USS Seattle, passed through the mouth of the Hudson River and into the Atlantic. Two hours later, the second group departed and two hours after that, the third group steamed. The fourth convoy group, carrying supplies, departed the following day. Gleaves arranged the groups’ speed in descending order, with the first convoy group having the fastest vessels and the fourth group having the slowest. Their departure was timed so that during the trans-Atlantic passage the speed difference between groups increased the time between their arrivals, permitting the small port of Saint-Nazaire to accommodate each group. Extreme caution was exercised by the convoys. Sixteen lookouts were posted during the day on each ship, and eight at night. Ships were completely darkened at night and radio silence was maintained throughout. The ships zigzagged to deny enemy submarines a clear shot.

The final portion of the passage was the most treacherous. Reminders of the submarine threat were all around. Wreckage from sunken ships bobbed on the surface and radio rooms were alive with S.O.S. calls from distant merchant vessels. As the convoy groups approached France, French warships ushered the American vessels into the Loire River estuary and Saint-Nazaire. The first group arrived at the French port at midnight on June 26, and by July 2, all four groups had reached their destination. The landing was a moral victory for the allies and a precursor to the two million American troops who ultimately would be transported to the European theater. The successful transport of troops was achieved mostly during the last six months of the war with almost no loss to German submarines. By July 1918, U.S. troops were arriving in France at a rate of about 10,000 per day, roughly half aboard U.S. shipping and half in other allied shipping. Although the U.S. Army had significant success on the battlefield against German forces, it was the German High Command’s realization that there was nothing it could do to stem the tide of an overwhelming number of U.S. troops on the battlefield that ultimately caused the Germans to sue for an armistice.

Operations in Former Yugoslavia

Recently, NHHC posted a new page on its website that covers the Navy’s role in peacekeeping operations in the Balkans.

The 1990s ushered in a new world order, with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the collapse of the Soviet Union seemingly imminent. By the end of 1991, the United States was the sole global power. This seismic shift challenged U.S. armed forces as they were frequently called on to address regional conflicts and disasters. Often, the United States struggled to find a balance between military force and diplomatic efforts. Facing this new reality, the Joint Chiefs of Staff recognized a need to clearly delineate between large-scale combat operations and specific military operations other than war (MOOTW). The MOOTW doctrine described specific types of operations from varying levels of direct combat—including air strikes, maritime intercept operations, and the enforcement of exclusion zones—to peace operations and the delivery of humanitarian assistance, all with the overarching goal of deterring war, resolving conflict, promoting peace, and supporting civil authorities. Officials believed that by enacting MOOTW, the United States could take the necessary steps to limit the possibility of American troops fighting in a large-scale war.

One implementation of MOOTW occurred following the collapse of Yugoslavia and the subsequent brutal wars in Bosnia and Herzegovina (informally known as Bosnia) and Kosovo.

For nearly a decade, U.S. armed forces, including the Navy, were deployed to the region to enforce United Nations resolutions attempting to bring the war and ethnic cleansing to an end through humanitarian assistance, naval embargos, economic sanctions, no-fly zones, and the establishment of safety zones. Eventually, when all diplomatic measures failed, the Navy, along with the other branches of the U.S. military, worked with NATO to strike Bosnian-Serb and Serb military targets and force them to the negotiating table to stop the wars that had claimed the lives of more than one hundred thousand people and displaced more than three million civilians.

For more, read the very informative essay, Operations in Bosnia and Herzegovina, by Communication and Outreach Division’s Jacqueline Evans at NHHC’s website.

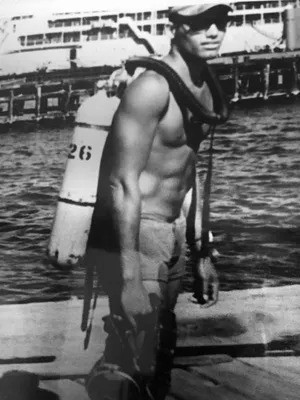

William “Bill” Goines was the first African American to serve as a Navy SEAL (Sea, Air, Land) when SEAL Teams 1 and 2 were formed in 1962.

First African American SEAL Passes Away

The first African American to serve as a Navy SEAL (Sea, Air, Land) died on June 10. Retired Master Chief Petty Officer William “Bill” Goines was 88 years old. Born in Dayton, Ohio, in 1936, as a child, he moved with his family to Lockland in suburban Cincinnati. His father worked in the automotive industry and had a second job in a pool hall. While in Lockland, Goines attended the all-black Wayne High School. In his junior year, after seeing the movie The Frogmen, which depicted underwater demolition teams during World War II, he was motivated to join the Navy. Shortly afterward, he went to see a recruiter but was told to finish high school first. Goines accepted having to wait another year, because he knew his mother would never let him drop out of high school. After receiving his diploma, Goines enlisted in the Navy in 1955. Goines was promised training in underwater demolition, but plans changed, and he was sent to Malta, where 11 months later, he eventually would begin frogman training with four U.S. Navy officers, 85 enlisted Sailors, five U.S. Army Rangers, and two foreign naval officers. After three weeks, most of the candidates had dropped out. Goines was one of only 14 to complete the challenging naval special warfare training. In January 1962, in response to President John F. Kennedy’s desire for the services to develop unconventional warfare, the U.S. Navy established SEAL Teams 1, on the U.S. West Coast, and 2, on the East Coast. Their mission was to conduct counter-guerilla warfare and clandestine operations in riverine and maritime environments. They were formed with personnel from underwater demolition teams. Goines was one of 40 chosen to join Team 2. At the time, he was the only African American Navy SEAL on either team.

Navy Parachute Team, circa 1984. Master Chief Bill Goines is pictured at the top right. He was the “Honor Student” for the team’s HALO (High Altitude, Low Opening) jump.

Goines went on to serve three tours during the Vietnam War with SEAL teams, twice with U.S. platoons and once leading a Vietnamese unit. In 1976, at 40 years old, Goines was selected to become part of the Chuting Stars, a Navy parachute demonstration team, with which he served for five years, performing 640 free falls and 194 static line jumps. During one jump in Pennsylvania, he landed awkwardly on a hill and “smashed all the cartilage” in his knees. Goines retired from the Navy in 1987 after 32 years. During his service, he was awarded the Bronze Star, the Navy Commendation Medal, the Meritorious Service Medal, the Combat Action Ribbon, and the Presidential Unit Citation. Following his discharge, Goines relocated to Portsmouth, Virginia, where he was employed as the chief of police for the Portsmouth school system, serving 14 years.

In September 2016, Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture opened in Washington, DC, and Goines was honored as part of the opening ceremony. As part of the museum’s collection, two patches that Goines wore during his naval service—a parachute team patch and a Navy Chuting Stars patch—are currently on display. In 2023, Goines was presented the Lone Sailor Award at the U.S. Navy Memorial, also in Washington, DC. The award is presented to “sea service veterans who have excelled with distinction in their respective careers during or after their service.” Retired Rear Adm. Julius Caesar nominated him for the award, noting, “At 87 years old, Master Chief William ‘Bill’ Goines is a towering figure who loves the Navy. He excelled as a Navy SEAL deploying on dangerous missions and was a part of the early establishment of the Navy SEALs in 1962. Master Chief Goines faced headwinds as the first African American Navy SEAL but overcame them through grit, determination, and a love of the nation. He’s an inspiration to all through his humility.”

Today in Naval History—Korean War Begins

On June 25, 1950, North Korea invaded South Korea, beginning the Korean War. Two days later, President Harry S. Truman authorized U.S. naval and air operations south of the 38th parallel in support of the United Nation’s call to assist South Korea. During the invasion, in four main avenues of approach, an armored brigade and six divisions with approximately 89,000 North Korean soldiers poured across the South Korean border. Spearheaded by about 200 Soviet T-34 medium tanks and 120 fighter and ground-attack aircraft, along with heavy artillery and with the advantage of tactical surprise, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea’s military quickly overwhelmed the 38,000 Republic of Korea troops in the northern part of South Korea. The South Korean forces who had no tanks, anti-tank weapons, or air support, very little training, and zero warning. The North Korean armored brigade and two divisions (3rd and 4th Infantry Divisions) marched directly toward the capital city of Seoul, only 30 miles south of the 38th parallel. Meanwhile, two other divisions (1st and 6th Infantry Divisions) attacked farther west before syphoning into Seoul, while the 7th Infantry Division attacked through the central mountains and the 5th Infantry Division attacked southward along the South Korean east coast. Initially, elements of the North Korean army entered Seoul but did not achieve their goal of a quick surrender and the collapse of the South Korean army. Instead, remnants of the Seoul-based forces formed a defensive line south of the Han River and on the east coast. However, after a brutal fight, Seoul fell to the North Korean army the following day. It was the first of four times the city would change hands during the Korean War.

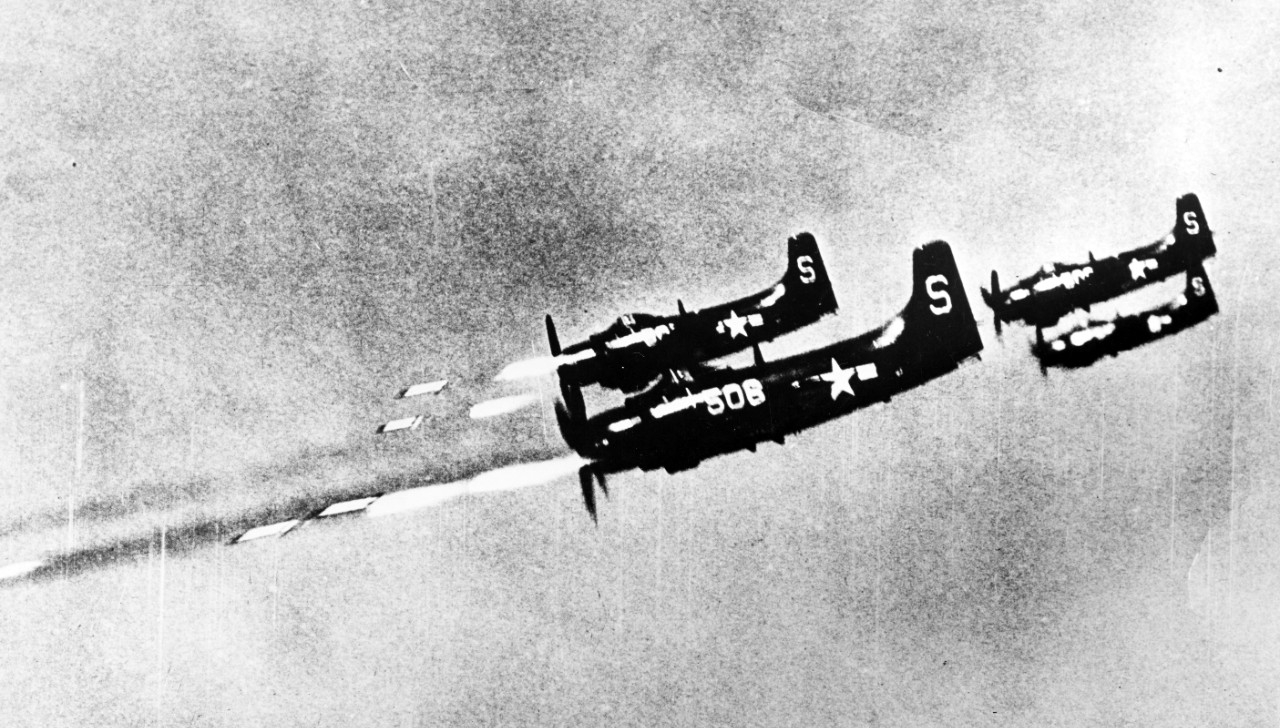

After evacuating about 1,600 U.S. citizens and friendly foreign nationals from Seoul on June 29, USS Juneau (CLAA-119) and USS De Haven (DD-727) fired the first naval shore bombardment of the war in the vicinity of Samchock, South Korea, destroying multiple enemy shore installations. A few days later, USS Valley Forge (CV-45) and HMS Triumph participated in the first carrier action of the war. Outnumbered and outgunned, South Korean troops battled desperately against tides of invading North Korean soldiers. Waves of Douglas AD Skyraiders and Vought F4U Corsairs struck the North Korean airfield at Pyongyang while Grumman F9F-2 Panthers flew top cover. Tons of bombs from the attacking American planes pounded hangars, fuel storage areas, parked Russian-built aircraft, and railroad marshalling yards. Meanwhile, the escorting Panthers downed multiple Soviet-built Yak-9 aircraft. However, despite attempts to interdict the steady flow of enemy troops, the North Koreans steadily pushed the South Koreans back into a defense perimeter around Pusan (today’s Busan).

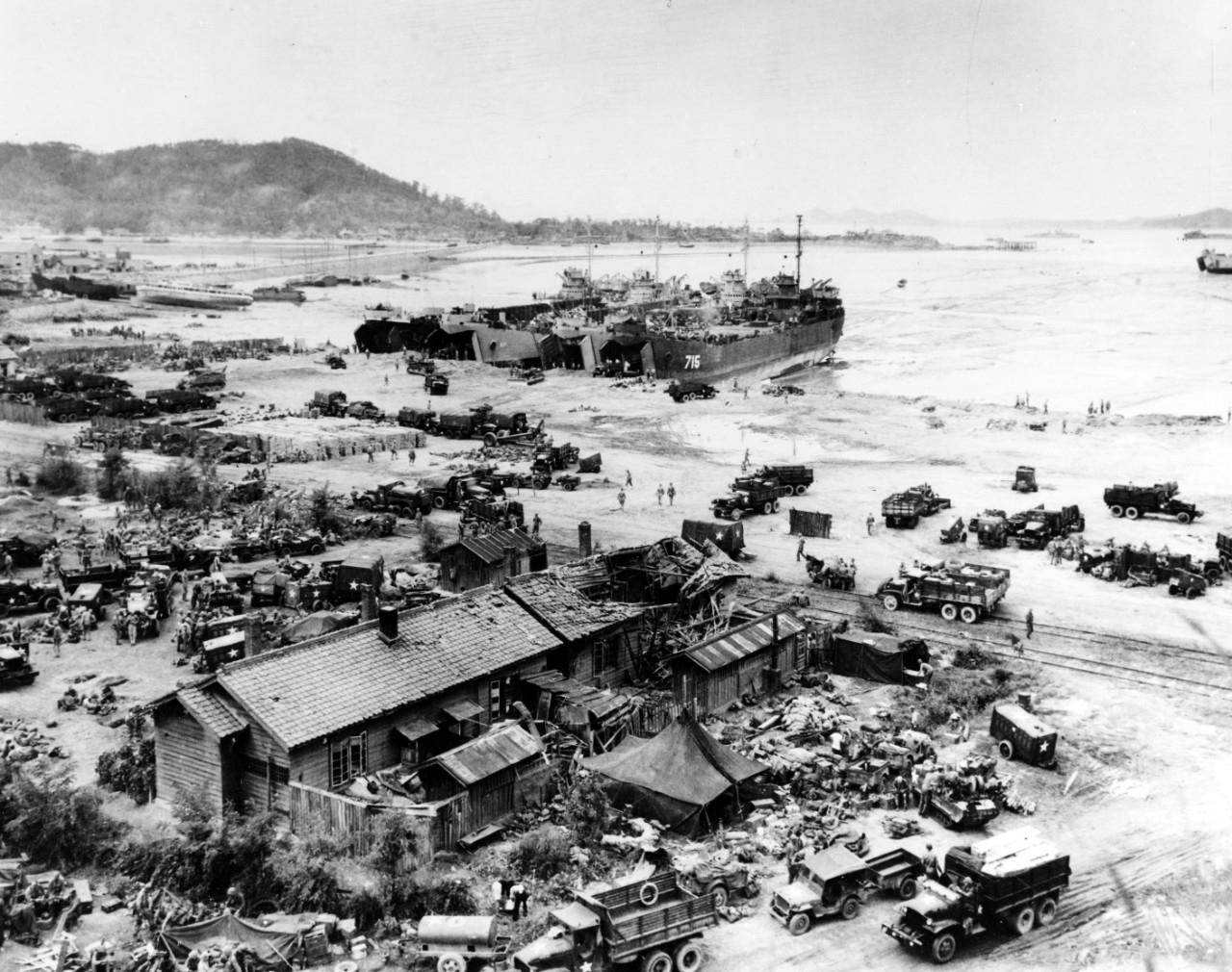

The first several months of the war were characterized by armies advancing and retreating up and down the Korean Peninsula. After the front stabilized at the Pusan perimeter, Gen. Douglas MacArthur surprised the North Koreans in September 1950 with an amphibious landing at Inchon behind enemy lines, forcing the North Koreans to retreat behind the 38th parallel. The following month, the United Nations—urged by the United States—approved the movement of UN forces across the 38th parallel into North Korea in an effort to unify the Korean Peninsula under a non-communist government. In spite of threats issued by the Chinese government, UN forces moved toward the Yalu River, which marks the North Korean border with Manchuria, China. Discounting the significance of initial Chinese attacks in late October, MacArthur ordered his forces to launch an offensive to the Yalu. In late November, the Chinese counterattacked in full strength, pushing UN forces back south of the 38th parallel and ultimately seizing Seoul again.

By early 1951, the Chinese offensive lost most of its momentum and UN troops retook Seoul, advancing back to the 38th parallel. The Korean War at this point was a “back-and-forth” fight with battle lines continually changing. By June, the Chinese/North Korean armies had grown to 1.2 million soldiers despite suffering about 500,000 casualties. UN casualties had risen to more than 100,000, and its troop strength was around 750,000. From July 1951 until the end of hostilities, the Cold War conflict was essentially a stalemate. President Truman’s administration subsequently abandoned plans to reunite North and South Korea and instead decided to pursue more limited goals in order to avoid the possible escalation of the conflict turning into a third world war involving China and the Soviet Union.

On Dec. 2, 1952, newly elected President Dwight D. Eisenhower went to Korea, and after visiting troops, their commanders, and South Korean leadership, sought an end to hostilities through diplomacy. Although peace negotiations had been ongoing since 1951 without few results, on July 27, 1953, an armistice was signed at Panmunjom (a tiny village located on the North and South Korean border) by officials from the UN, North Korea, and China. The armistice ended organized combat operations, left Korea divided, and is still in place today.

From the U.S. Navy’s perspective, due to neither North nor South Korea having major sea services, the war featured few naval battles, and vessels from the UN had undisputed control of the sea surrounding Korea. Destroyers, cruisers, and battleships were used for shore bombardments, and aircraft carriers provided aerial support for boots on the ground. For most of the war, UN naval forces patrolled the west and east coasts of North Korea, sinking supply and ammunition ships and denying the North Koreans the ability to resupply from the sea. Aside from the occasional gunfire from North Korean shore batteries, the biggest danger to Navy ships was magnetic mines. During the war, the U.S. Navy lost five ships to mines.

During the so-called forgotten war, the United States suffered more than 36,000 fatalities. Approximately two to three million civilians were also killed, and in wake of the war, South Korea was reduced to rubble. After the armistice was signed, more than one million North Koreans fled to South Korea. Many families were forever torn apart by the war. Seven U.S. Navy Sailors and 42 Marines were awarded the Medal of Honor for their gallant actions during the Korean War. Forty-four Sailors and 221 Marines were awarded the Navy Cross.