Welcome to Navy History Matters—our biweekly compilation of articles, commentaries, and blogs related to history and heritage. Every other week, we’ll gather the top-interest items from a variety of media and social media sources that link to related content at NHHC’s website, your authoritative source for Navy history.

Compiled by Brent A. Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command Communication and Outreach Division

Port Chicago Disaster@80

On the evening of July 17, 1944, two cargo ships—SS Quinault Victory and SS E. A. Bryan—were berthed at the munitions pier at Port Chicago Naval Magazine, California, when massive explosions rocked the base. At 10:18 p.m., a dull clang and the sound of splintering wood preceded a blinding flash and a substantial detonation on the pier, followed within seconds by smaller detonations and then the massive explosion of munitions in E. A. Bryan’s holds. On board E. A. Bryan or on the pier ready to be loaded were 4,606 tons of antiaircraft ammunition, aerial bombs, high explosives, and smokeless powder. The ship, most of the pier, all structures within a 1,000-foot radius, and many of the flatcars were literally disintegrated. The explosion blew Quinault Victory into pieces that subsequently sank in the waters of the bay. A Coast Guard fire barge was blown away from the munitions pier and sank, killing its crew of five. The 320 individuals in the immediate proximity of the blasts—Navy personnel on loading details, a Marine Corps sentry, the ships’ Navy armed guard and merchant mariner crews, and civilian employees—were killed instantly. Of those killed, only 51 were able to be identified in the aftermath. Most of the personnel killed were African American Sailors. More than 250 other personnel were injured, many seriously. Most of the buildings on base were damaged, and many were completely destroyed. Secondary fires raged and munitions continued to cook off for some time after the explosion of E. A. Bryan. The shock of the detonations could be felt as far away as San Francisco, 40 miles to the southwest, and even in parts of Nevada.

On July 21, a Navy court of inquiry convened and over the next 39 days conducted its investigation on the Port Chicago disaster. The court’s primary focus was on training and operational practices prior to the disaster. As Port Chicago was racially segregated, much of the investigation was focused on the personal and professional challenges of a segregated command. As was common at the time, the court’s report strongly implied that specific attributes of African American enlisted personnel had slowed training evolutions and day-to-day operations, and made them more difficult. However, in the court’s opinion, the explosions and the subsequent loss of life were not due to negligence or inefficiency. Although the exact cause of the explosions was never determined due to a lack of eyewitnesses and extensive destruction of the pier, a number of shortcomings could have contributed to the disaster, according to the court. The shortcomings included the following: Port Chicago was at its operational capacity; there were shortfalls in munitions handling; override of basic safety procedures occurred; and instructions did not sufficiently cover all aspects of ordnance safety and handling in port during wartime.

Soon after the disaster, surviving ordnance personnel were transferred from Port Chicago to Mare Island Naval Shipyard, also in California. While there, the Sailors were once again assigned to ordnance loading duties, similar to what they experienced at Port Chicago. Clearly, they were still shaken by the disaster and approached their tasks with a high degree of uneasiness. Finally, on Aug. 9, 328 battalion ordnance Sailors refused to carry out their duties unless safety procedures were improved. After appeals from their officers, 70 workers agreed to go back to work under the current conditions. On Aug. 10, Rear Adm. Carleton H. Wright, commander of the Twelfth Naval District, gave the remaining 258 Sailors an ultimatum—go back to work or their actions would be considered mutiny and the consequences would be severe. Ultimately, 50 Sailors, later known as the “Port Chicago 50,” stood their ground. The 208 that did return to work were given summary court- martials and docked three months’ pay. The Port Chicago 50 were charged with disobedience of a lawful order and mutiny. Ultimately, the men received sentences from 8 to 15 years of confinement and would be dishonorably discharged. With some prodding from future Supreme Court justice Thurgood Marshall (NAACP chief counsel at the time), Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal ordered the Navy to review the case, but ultimately the court reaffirmed the original sentences. However, pressure from several high-level individuals and organizations, including former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, prompted Forrestal to have the convicted Sailors released from confinement in January 1946. The men were dispersed among various ships deployed in the Pacific, performing menial duties until receiving general discharges under honorable conditions. As late as the 1990s, they and their descendants repeatedly appealed to Congress and the Navy to have their names and records cleared. Recognition finally occurred on July 17, 1994, when the Port Chicago Naval Magazine National Memorial was dedicated to those lost in the disaster. Freddie Meeks, at the time thought to be the last surviving known member of the Port Chicago 50, received a Presidential pardon in December 1999. However, complete exoneration of all 50 Sailors has not occurred to date.

The First Lady of Naval Cryptology

Although she cracked a multitude of Japanese naval code systems, trained nearly all of the U.S. Navy’s leading World War II cryptanalysts, and was inducted into the National Security Agency’s Cryptologic Hall of Honor at Fort Meade, Maryland, Agnes Meyer Driscoll is still a relatively unknown figure in naval history.

Born on July 24, 1889, in Geneseo, Illinois, she studied mathematics at Ohio State University and minored in music, physics, and foreign languages. After graduating in 1911, she taught music at a military school in Amarillo, Texas. She left that position in 1915 to teach mathematics at Amarillo High School. Three years later, she enlisted in the Navy as a yeoman (F).

Driscoll (Agnes married lawyer Michael Driscoll) was working at the U.S. Navy’s Office of the Chief Cable Censor as a yeoman first class where she indexed, filed, and forwarded incoming and outgoing telegrams. She was promoted to chief yeoman and transferred to the Naval Communication’s Code and Signal section, where she studied the Navy’s code and cipher systems. After leaving active duty in July 1919, she immediately began working as a Navy civilian in the same office. Although her official job title was clerk/stenographer, she mostly did cryptologic work. She worked her way up to senior administrative assistant before being promoted to cryptanalyst.

In 1923, she left the federal government to work in the private sector for Edward Hebern, a cipher machine inventor. While there, Driscoll co-developed a cipher machine with Lt. Cmdr. William F. Gresham, which went into production that year. She developed the cryptographic principle for the CSP-523 cipher machine, while Gresham invented the bones of the mechanism. Hebern wanted to sell his own cipher machine to the Navy, but he needed to make it cryptographically secure first, so he hired Driscoll as a technical advisor. However, Hebern’s company failed to get enough federal contracts, and Driscoll returned to government service a year later.

Driscoll spent the next three decades working as a Navy cryptanalyst. She became the principle cryptanalyst for the Navy and went on to train generations of active duty cryptologic officers, including Capt. Laurance Safford, Cmdr. Joseph J. Rochefort (later of Battle of Midway fame), Capt. Thomas Dyer, and Capt. Edwin T. Layton. She also cracked several of Japan’s operational codes—the “Red Book” and “Blue Book”—and the JN-25 code. She worked on the Enigma project—cracking the German navy’s operations code—as well. Although she did not have as much success in cracking the Enigma code as the British did, she did assist in the effort by co-inventing the Driscoll-Howard Standard Grenade. This cryptographic machine reduced the effort needed to identify the window settings of the Navy’s electromechanical “Bombe” machines that were used to decode German Enigma machine’s encrypted messages. Driscoll retired in 1959. She is featured in the NSA’s Cryptologic Hall of Honor. Driscoll died in 1971 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

For more on the first lady of naval cryptology, read the article by Communication and Outreach Division’s Wendy Arevalo at NHHC’s website.

Battle for Guam—80 Years Ago

On July 21, 1944, Task Force 53, commanded by Rear Adm. Richard L. Connolly, landed the 3rd Marine Division and the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade, along with the U.S. Army’s 77th Infantry Division, on Guam. As part of Operation Forager, the recapture and liberation of the U.S. territory of Guam, which had been captured by the Japanese on Dec. 8, 1941, was originally planned to take place about a month earlier. However, due to the Battle of the Philippine Sea and the unexpected enemy resistance on Saipan, the operation had to be temporarily postponed. Guam, located in the southernmost part of the Marianas, was heavily defended by approximately 19,000 Japanese troops that had many well-constructed defensive positions in place. Task Force 58 bombarded the island on June 11–12 and again on June 16 and 19 during the Battle of the Philippine Sea. From July 8 until D-Day, Connolly’s force carried out a systematic bombardment of the enemy that was augmented by naval air strikes. Prewar intelligence of Guam’s terrain and hydrography was available, but more recent intelligence, mainly imagery of possible landing beaches collected since April by U.S. submarines, was particularly helpful in planning the operation. The submarine force’s contribution to the mission was augmented by aerial photographs and by reconnaissance missions undertaken by underwater demolition teams (UDTs). The focus of the UDTs was to identify the presence of underwater obstacles and assess the beaches for large-scale amphibious landings. Beginning on June 18, the “frogmen” blew up nearly 1,000 Japanese-planted coral and concrete boxes off the designated landing beaches at Asan (northern sector) and Agat (southern sector), both on Guam’s western side.

On July 21, the 3rd Marine Division landed at Asan, while the 1st Provisional Brigade landed at Agat. The Army’s 77th Division was initially retained as a floating reserve off the southern beaches. At Asan, landing craft were temporarily denied access to the beaches by a coral reef. However, the 3rd Marine Division was shifted at the reef line from their landing craft to amphibious tractors that carried them to shore. In both the northern and southern sectors, landing forces were met with heavy enemy resistance, and although pre-invasion bombardments and air strikes had destroyed many of the Japanese above-ground positions and facilities, underground positions mostly stayed intact, slowing the American advance. In the north, Marines faced several ferocious counterattacks, which they were able to repulse. Loss of scores of Japanese senior officers and naval gunfire on their assembly areas kept the enemy from effectively reinforcing their thrusts into American lines. In the first week, despite serious losses, the 3rd Marine Division had consolidated its beachhead and advanced toward the center of the island.

Meanwhile, the landing force at Agat faced a determined enemy supported by mortar and artillery fire that immobilized numerous American amphibious tractors. By late afternoon, Agat village was captured, but the fighting continued. Loss of amphibious tractors hampered the logistics chain and also delayed landing troops of the 77th Infantry Division. Japanese counterattacks, mostly supported by tanks, continued through the night but were repulsed. Naval vessels provided star shell illumination and fire support throughout nighttime operations. In the south, Marines battled their way north onto the Orote Peninsula and its airfield. On July 25, a final banzai charge took place, but the Japanese last-ditch effort was unsuccessful. On the afternoon of July 28, Orote was secured by the Marines. Meanwhile, Soldiers of the 77th Infantry Division pushed east and north to link up with northern forces. As part of a fighting withdrawal, Japanese forces retreated to Guam’s mountainous northeast around Mount Santa Rosa.

On July 31, the 3rd Marine Division and 77th Infantry Division, with the 1st Provisional Brigade in reserve, began their final push. The town of Agana was seized the same day, and American forces reached their daily objectives—key points on Guam’s roads—by that evening. The advance continued through the first week of August. The 77th Infantry Division captured Mount Saint Rosa on Aug. 7–8, and Marines and Soldiers reached key points on Guam’s northern and eastern coasts by Aug. 8. Two days later, the island was declared secured, and organized resistance had ceased. Despite a small number of Japanese troops who held out in the island’s jungles until after Japan’s surrender, Guam was transformed into a major logistical base that would support the upcoming liberation of the Philippines.

Today in Naval History—Thresher Launched

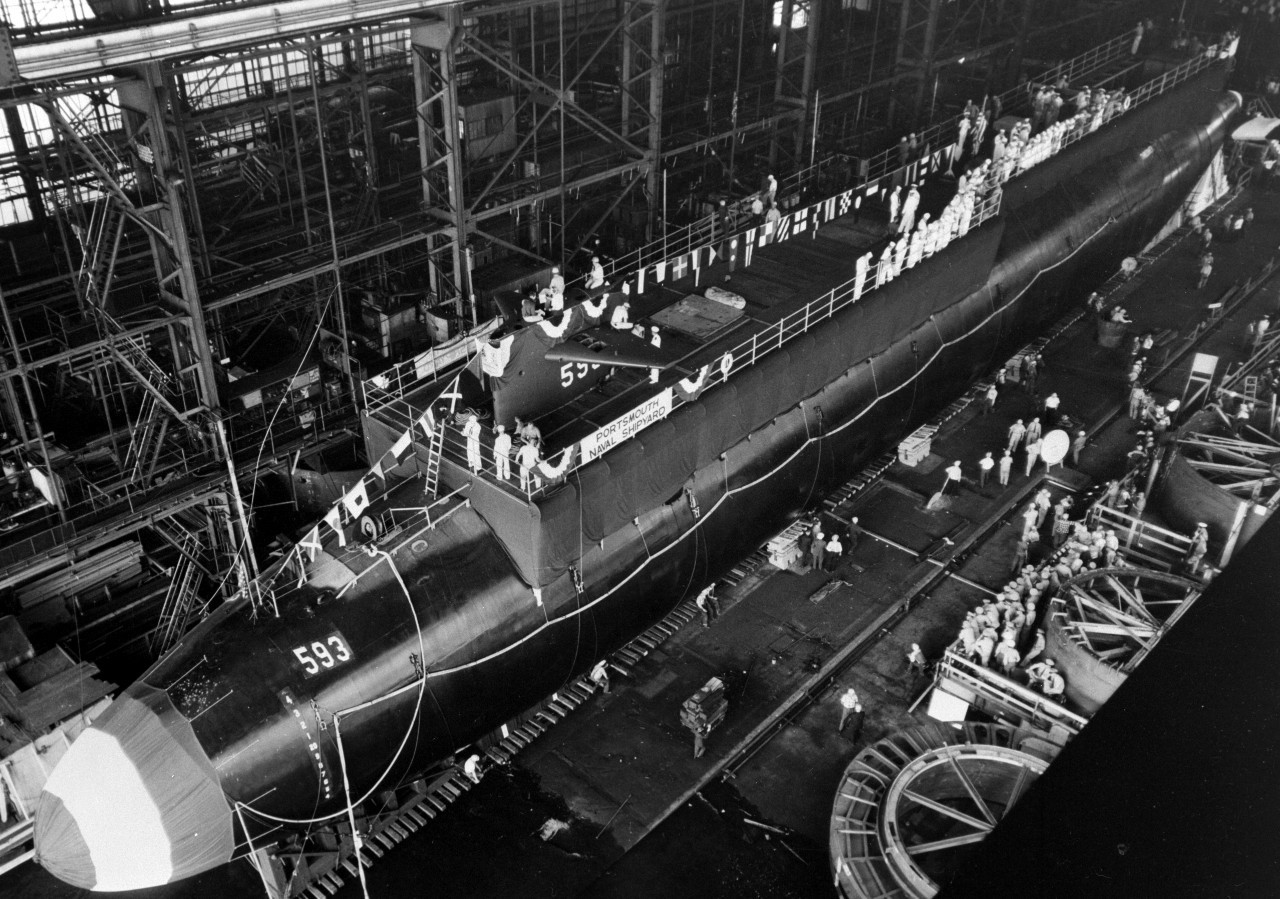

On July 9, 1960, USS Thresher (SSN-593) was launched at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, Kittery, Maine. The boat was sponsored by Mary Warder, wife of Rear Adm. Frederick B. Warder, a decorated World War II submariner and, at the time, the commandant of the Eighth Naval District. It was commissioned on Aug. 3, 1961. Following trials, the nuclear attack submarine took part in Nuclear Submarine Exercise (NUSUBEX) 3-61 off the northeastern coast of the United States, Sept. 18–24, 1961.

On April 9, 1963, Thresher put to sea with 129 aboard for deep diving exercises. The submarine rescue ship USS Skylark (ASR-20) was assigned to escort the submarine. They rendezvoused at about 10 a.m. and proceeded to conduct the first day of operations without incident. The ships independently proceeded to a second meeting point where the second day of exercises would take place.

At 7:45 a.m. on April 10, Thresher reported that Skylark was in the vicinity, roughly southeast by south, 3,400 yards away. Underwater telephone communication (UQC) linked Thresher and Skylark, providing the means of voice communication. At 7:47 a.m., Thresher reported via the UQC that it was commencing a deep dive and, over the ensuing time period, kept Skylark apprised of changes in its course and depth. By 9 a.m., calm seas prevailed with a slight swell. Visibility was about 10 miles, and no other vessels were in the immediate area. Thresher reported to Skylark at 9:13 a.m. that the boat was “experiencing minor difficulties,” it had a “positive up angle,” and was “attempting to blow [ballast].” The message ended with, “Will keep you informed.” Three minutes later, Skylark heard a garbled transmission that included the words “test depth.” A few moments later, Skylark received another garbled transmission over the UQC that contained the words, “nine hundred north.” Shortly thereafter, “a high-energy, low- frequency noise disturbance of the type which could have been made by an implosion” emanated from Thresher. Efforts to reestablish contact with Thresher failed, and a search group was formed in an attempt to locate the submarine. Rescue ship USS Recovery (ASR-43), first on the scene, subsequently recovered bits of debris, including gloves and bits of internal insulation. Photographs taken later by Bathyscaphe Trieste proved that the submarine had broken up, taking all 129 on board to the bottom. Thresher was stricken from the Naval Vessel Register on April 10, 1963.

The exact sequence of events that led to Thresher’s loss is still debated today. However, a court of inquiry concluded that Thresher probably suffered a weld failure in a saltwater piping system, leading to flooding and a reactor shutdown, which then resulted in an inability to control depth and prevented it from reaching the surface. This conclusion may have been compounded by possible ice in the valves used to blow the main ballast tanks, which prevented it from reaching the surface by an emergency de-ballasting blow. On the other hand, acoustic experts have argued that at maximum depth at which Thresher was operating, the pressure was so great that any leak would have resulted in a major acoustic event, which was not detected on acoustic recordings of the sinking. This would suggest something other than flooding led to the reactor shutdown. Regardless, the loss of the lead boat of the most advanced class of submarine designed and built to that date was a significant event, and the fact that it was a nuclear submarine only added to the traumatic disaster. However, the result was an extensive top-to-bottom review of all aspects of submarine design, construction, training, and operation. Key aspects of the review were organized as the Submarine Safety Program (SUBSAFE). SUBSAFE provides a maximum reasonable assurance of the integrity of submarine design, systems, and materials via design review, shipboard system testing, and objective quality evidence that all materials and components meet drawing and specification requirements. Since the full implementation of SUBSAFE in the entire submarine fleet in 1968, there have been no incidents of the Thresher’s magnitude to date. The program is so effective that NASA has used it. The agency worked with the Navy to reevaluate two of the biggest disasters in NASA’s history—the losses of space shuttle Challenger in 1986 and space shuttle Columbia in 2003.