Welcome to Navy History Matters—our biweekly compilation of articles, commentaries, and blogs related to history and heritage. Every other week, we’ll gather the top-interest items from a variety of media and social media sources that link to related content at NHHC’s website, your authoritative source for Navy history.

Compiled by Brent A. Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command Communication and Outreach Division

The Tragic Loss of Indianapolis

Shortly after midnight on July 30, 1945, Japanese submarine I-58 sank USS Indianapolis (CA-35) northeast of Leyte with two torpedo strikes against the heavy cruiser’s starboard side forward. Ultimately, only 316 of its 1,195 crew survived the attack and the subsequent fight for survival in the open ocean. Due to communication and other errors, the loss of Indianapolis went unnoticed until survivors were spotted by a passing plane days later. Prior to its sinking, Indianapolis had just delivered atomic bomb components to Tinian, which would ultimately contribute to Japan’s surrender and end World War II in the Pacific. After the Portland-class heavy cruiser fell prey to Cmdr. Mochitsura Hashimoto’s submarine, fire and chaos ensued, and in the next 12 minutes, 330 of the crew went down with the ship as it quickly sank, while the rest, approximately 880 crewmembers, were left adrift in the Philippine Sea in the middle of the night. For the next few days, without food or water, suffering exposure, dehydration, drowning, and shark attacks, the crew battled the elements and clung to life as best they could before they were finally rescued.

When the ship did not reach Leyte on July 31 as scheduled, a report wasn’t made that it was overdue. This omission was due to a misunderstanding of the Movement Report System (used to monitor and track vessel movements). Thus, it was not until at 10:25 a.m. on Aug. 2 that the survivors were finally sighted, mostly kept afloat by life jackets, although there were a few rafts that had been cut loose before the ship went down. The pilot who discovered them immediately dropped a life raft and a radio transmitter. All air and surface units capable of rescue operations were dispatched to the scene at once, and the surrounding waters were thoroughly searched for survivors. Upon completion of rescue operations on Aug. 8, a radius of 100 miles had been searched by day and by night. Although he was initially court martialed, Capt. Charles B. McVay, commanding officer of Indianapolis, was deemed to be free from any blame resulting from the loss of his ship. All personnel involved in the failure to report the ship’s absence from Leyte were also exonerated, after all the evidence had been carefully weighed. Secretary of the Navy Gordon England ordered that a congressional letter exonerating McVay posthumously be placed in his official file in 2001.

Commissioned in November 1932, Indianapolis received 10 battle stars for its service during the war. The heavy cruiser participated in such naval battles as the Aleutians campaign, Gilbert Islands operation, Battle of Saipan, Battle of the Philippine Sea, occupation of Guam and Tinian, Battle of Iwo Jima, and the Battle of Okinawa. The ship was seriously damaged off Okinawa by a bomb from a kamikaze that blew two gaping holes in the ship bottom and flooded compartments in the area, killing nine of its crew. Indianapolis managed to stay afloat for emergency repairs before it headed back to the Mare Island Navy Yard, California, for an overhaul and permanent repairs. During its tenure, the ship also served as President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s ship of state during the 1930s and as Adm. Raymond Spruance’s Fifth Fleet flagship between 1943 and 1944.

In July 2016, 71 years after the tragedy, survivors and family members gathered in Indianapolis, Indiana, to honor and remember the Sailors and Marines of Indianapolis. NHHC’s director, retired Rear Adm. Sam Cox, was on hand as the keynote speaker for the event. He noted, “There is no question that the loss of USS Indianapolis is one of the blackest episodes in the history of the U.S. Navy. But I also believe that even in loss and tragedy, there are examples of extraordinary valor and sacrifice that deserve to be remembered, that serve as an inspiration to Sailors today and in the future, and there are lessons learned that must be preserved and passed on, and are relevant even now. The Indianapolis story has these in abundance.” At the time, there were 10 of 23 surviving crewmembers in attendance for the reunion.

On Aug. 12, 2017, a team of civilian researchers led by entrepreneur and philanthropist Paul G. Allen announced they had found the wreck of Indianapolis. The wreck was located by the expedition crew of research vessel Petrel, which was owned by Allen, 5,500 meters below the surface, resting on the floor of the North Pacific Ocean. “To be able to honor the brave men of the USS Indianapolis and their families through the discovery of a ship that played such a significant role in ending World War II is truly humbling,” said Allen shortly after the discovery. “As Americans, we all owe a debt of gratitude to the crew for their courage, persistence and sacrifice in the face of horrendous circumstances. I hope everyone connected to this historic ship will feel some measure of closure at this discovery so long in coming.”

As for the crew, there is only one living survivor left, Harold Bray, who just turned 97 in June. He was only 17 years old serving as a seaman second class when Indianapolis was sunk. He joined Indianapolis when the ship was under repair at Mare Island following the March 1945 kamikaze attack off Okinawa. It was his first assignment following boot camp. In July 2023, a monument of Bray was unveiled in his hometown of Benicia, California. The bronze statue portrays him as a young Sailor with a grin on his face, full of confidence.

For more on the ship, the crew, and the aftermath, visit the Indianapolis notable ship page on NHHC’s website. It contains links to books, primary documents and imagery, lessons learned, story map, and much more.

The Navy’s First Aerobatics Team—“Three Sea Hawks”

Following World War I, the U.S. government began lifting wartime prohibitions on civilian flying, sparking a resurgence of aviation as a form of public entertainment. During the two-decade interwar period known later as the “Golden Age of Aviation,” civilian aviation enthusiasts benefitted from military surplus aircraft produced to train pilots during the war and the return of military aviators from overseas. Air races and barnstorming, a style of flying in which pilots performed tricks in an airplane either individually or in group formations, became increasingly popular. Although stunt flying sparked concern among investors who believed it would discourage the public from thinking of the airplane as a form of travel for passengers, nonetheless ambitious aviators pushed the envelope and their aircraft to its physical limits as the crowds expected more with each performance.

After witnessing the aerobatics of the Army Air Corps’ “Three Musketeers,” led by Lt. James Doolittle, naval aviator Lt. Daniel W. Tomlinson, IV, sought advice how to modify F6C carburetors in the same fashion Doolittle had so that naval aircraft would not cut out when they were inverted. He had modified the carburetors in the Army’s Curtiss PW-8 Hawks (the same airframe as the Navy’s F6C) to allow the aircraft to sustain inverted flight for 45 seconds. Not happy with the Navy’s performance at that air show, Tomlinson was determined to improve the capabilities of naval aircraft and create his own team for the next demonstration.

After he returned to San Diego, Tomlinson handpicked two other pilots for his proposed aerobatics section—Lt. (j.g.) William V. Davis, Jr, and Lt. (j.g.) Aaron P. Storrs, III. Once he had the pilots, they began practicing at Naval Air Station North Island, California. The Boeing FB-5, then flown by Tomlinson’s squadron, was not ideal for what they were doing, but it was better than the Vought VE-7 they had been flying the prior year while carrying out trial flight operations. However, in January 1928, Tomlinson’s squadron, based on aircraft carrier Langley (CV-1), was due to receive a new aircraft, the Boeing F2B-1. Thirty-three were ultimately delivered with three allocated to Tomlinson’s squadron. This would be the first aircraft flown by the Navy’s first aerial acrobatics team, 18 years before the establishment of the Blue Angels. The F2B’s specifications initially did not permit inverted flight. However, Tomlinson requested a modification of the carburetors, per Doolittle’s advice, to carry out the stunts that he wished to perform.

The aerobatic team was not official, however. Their training sessions were kept quiet, and neither Tomlinson nor his wingmen were officially assigned this duty. Initially, they trained over land and above the clouds near San Diego, and despite attempting to keep their activities quiet, their stunts did attract attention when the pilots could not resist the temptation to show off. As soon as they had an opportunity, Tomlinson’s leadership put the performance on public display. In April 1928, Tomlinson’s squadron was aboard Langley headed to San Francisco with 35 planes crowding the flight deck. Tomlinson’s team joined 26 other aircraft launched from the carrier on April 12 for an aerial show over the city. During the demonstration, Tomlinson claimed to have flown inverted over the buildings along Market Street, and the team demonstrated several outside and inverted loops. However, San Francisco’s typical overcast skies made it difficult for naval leaders and civilians on the ground to see the demonstration.

Following the show in San Francisco, the carrier departed for a strategic exercise off the coast of Hawaii. During the exercise, the squadrons assigned to Langley were able to launch 35 aircraft in just seven minutes. Unlike the aerial show over San Francisco where Tomlinson’s team—now known as the “Three Sea Hawks”—carried their more dangerous stunts out of the Navy leadership’s view, they put on a complete show for the commanding officer of Langley, Cmdr. John H. Towers. Afterward, Towers said, “Tomlinson, I think the Air Corps has been sufficiently impressed.” It was likely a subtle hint to stop what he was doing, but Tomlinson took it as a compliment and permission to continue practicing, just not during fleet exercises. The following month, Tomlinson’s team was directed to “put on a show” over San Francisco again.

Shortly after the second San Francisco demonstration, Secretary of the Navy Curtis Wilbur issued a directive prohibiting naval aviators from attempting inverted or outside loops unless expressly permitted. It was unlikely that this statement was directly related to Tomlinson’s own activities since the exception provided a “loophole” for aerial demonstrations by trained aviators such as Tomlinson. Wilbur’s directive may have been urged by the early airline industry, which wished to shift the public perception of aviation safety. Stunts and accidents in the news did not help their efforts, even if the pilots involved were military aviators. Previously, in April 1928, the Secretary of the Navy had responded to this pressure by appointing a board to investigate developing more safety in naval aviation because of the high fatality rate. The demonstrations by Tomlinson’s trio were risky, but Rear Adm. Joseph M. Reeves seemed to understand the value of this team and what they could do at a time when it was politically precarious to support their activities.

Reeves proposed another public display in August of that year. Despite the recent limitations placed on Navy planes performing stunts in public exhibitions, there were allowances made for the “dedication of airports and landing fields or features having naval or military significance.” Secretary of the Navy Wilbur received a preview of the coming event and allowed the air show to go forward as planned. At the dedication of Lindbergh Field on Aug. 16 in San Diego, the U.S. Navy flew approximately 222 planes over the city in a demonstration of aerial strength. The aerobatics of the Three Sea Hawks were only part of the spectacle. They performed a series of loops, rolls, and dives. Reeves provided commentary throughout the whole show, in full support of his naval aviators, including the Three Sea Hawks.

For more on the Navy’s first aerobatic team, read the essay, The Three Sea Hawks, by Communication and Outreach Division’s Kati Engel at NHHC’s website.

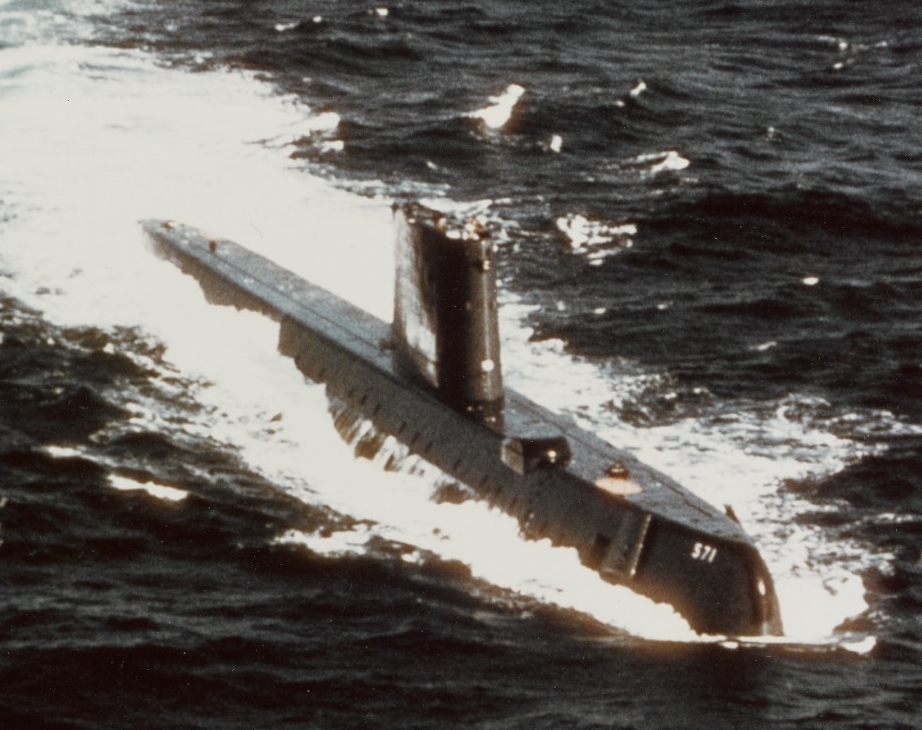

First Fully Submerged Transit Under North Pole

On Aug. 3, 1958, USS Nautilus (SSN-571) became the first submarine to a conduct a fully submerged transit under the geographic North Pole during the highly secretive Operation Sunshine. “For the world, our country, and the Navy—the North Pole," declared the boat’s commanding officer, Cmdr. William R. Anderson. The mission had been personally authorized by President Dwight D. Eisenhower as a response to the USSR’s Sputnik program, and he subsequently awarded Nautilus the Presidential Unit Citation. Nautilus began the mission on June 9 when it departed Seattle. However, the first attempt was blocked by drift ice in the relatively shallow waters of the Chukchi Sea, and the submarine made way to Pearl Harbor. Its second attempt, begun on July 23, proved successful. Nautilus submerged in the Barrow Sea on Aug. 1, transited the North Pole, and, after running submerged an additional 96 hours, surfaced off Greenland on Aug. 7.

The construction of Nautilus, the world’s first nuclear-powered submarine, was made possible by the successful development of a nuclear propulsion plant by a group of scientists and engineers, under the leadership of Capt. Hyman G. Rickover, at the Naval Reactors Branch of the Atomic Energy Commission. After sea trials and preliminary acceptance by the Navy, Nautilus headed south for shakedown on May 10, 1955. While en route to Puerto Rico, it remained submerged, traveling 1,381 miles in 89.8 hours, the longest submerged cruise to that date by a submarine and at the highest sustained submerged speed ever recorded for a period of more than one hour’s duration. The following year, Nautilus operated out of Naval Submarine Base New London, Connecticut, where the effects of a submarine with increased speed and endurance were tested on contemporary anti-submarine warfare practices. The study found that anti-submarine practices, such as were used during World War II, were ineffective against a submarine that did not need to surface, could dive deeper, and could clear a search area in record time.

On Feb. 4, 1957, Nautilus logged its 60,000th nautical mile. It also marked another first for the boat, as the submarine was put into the Electric Boat Company Division of General Dynamics Corporation at Groton to replace the nuclear fuel core in its Westinghouse Electric submarine thermal reactor. In early April, Nautilus operated off Bermuda with USS Seawolf (SSN-575)—the second nuclear-powered submarine—before departing for the U.S. West Coast on May 15. While there, Nautilus participated in multiple exercises designed to acquaint the units of the Pacific Fleet with the capabilities of nuclear submarines. It returned to New London on July 21. On Aug. 19, Nautilus departed New London for its first voyage under the Arctic polar ice pack. The 1,383-mile journey was significant because earlier conventional U.S. diesel-electric submarines did not travel to the frozen northern oceans since they could not travel freely under ice. The opening of the Arctic to Navy submarines allowed access to the previously protected coastal waters of the Soviet Union.

After its record-breaking transit of the North Pole in 1958, Nautilus continued to focus on evaluation tests for anti-submarine warfare improvements and various NATO exercises in the Atlantic. In the spring of 1966, it again entered the record books when it logged its 300,000th mile underway. During the following 12 years, Nautilus was involved in a variety of developmental testing programs while continuing to serve alongside many of the more modern nuclear-powered submarines it had preceded.

On April 9, 1979, Nautilus departed Groton on its final underway, steaming south to the Panama Canal via Guantanamo Bay and Cartagena, Columbia. From there, it cruised north and reached Mare Island Naval Shipyard, Vallejo, California, on May 26, to begin inactivation procedures. The groundbreaking submarine was decommissioned on March 3, 1980.

In recognition of its pioneering role in the practical use of nuclear power, Nautilus was designated a National Historic Landmark by the Secretary of the Interior on May 20, 1982. Following an extensive historic ship conversion at Mare Island, the submarine was towed to Groton, arriving on July 6, 1985. There, on April 11, 1986, 86 years to the day of the establishment of the U.S. Submarine Force, historic ship Nautilus and Naval History and Heritage Command’s Submarine Force Museum opened to the public as the first exhibit of its kind in the world. The unique museum ship continues to serve as a dramatic link in both Cold War–era history and the birth of the nuclear age.

Today in Naval History—Constitution Refloated

On July 23, 2017, after 26 months of restoration at Dry Dock #1 at the Charlestown Navy Yard in Boston, the world’s oldest commissioned warship afloat and the world’s oldest sailing vessel still capable of sailing under its own power, USS Constitution, was refloated. Since entering dry dock on May 18, 2015, ship restorers from Naval History and Heritage Command’s Detachment Boston and teams of Constitution Sailors worked diligently to bring “Old Ironsides” back to its glory. The restoration consisted of the replacement of 100 hull planks and the required caulking, the rebuilding of the ship’s cutwater on the bow, and the ongoing preservation and repair of the ship’s rigging, upper masts and yards. One of the most highly anticipated tasks of the restoration was the replacement of Constitution’s copper sheathing below the waterline. Since the ship launched in 1797, copper sheathing has covered the lower hull as protection. This was one part of the restoration that saw Constitution’s Sailors get hands-on with the preservation. Sailors helped Detachment Boston ship restorers replace 2,200 sheets of copper and the felt that is installed behind it. Constitution re-opened to the public in early September 2017 after post-docking restoration work was completed.

Constitution began service in the Navy on Oct. 21, 1797. It was one of the six original frigates that constituted the Navy’s first fleet, and construction was authorized by an act of Congress in 1794. It and its sister frigates were designed by shipbuilder Joshua Humphreys. As the Navy’s principal ships, they were larger and more heavily armed than the frigates that had come before them, making them formidable opponents on the high seas. Constitution’s keel was laid in Edmund Hartt’s Shipyard in Boston and was built from the resilient Southern live oak from Georgia. Its three masts were made from the strong white pine of Maine. Humphreys designed the hull to be 22 inches thick at the waterline. Undefeated in battle, the ship fought valiantly on the high seas during the Quasi War with France, the Barbary Wars, and, most notably, the War of 1812 against Great Britain. Constitution’s defining and most historic battle was with the British frigate HMS Guerriere during the War of 1812, during which one of the American Sailors noticed that some of the enemy’s cannon balls appeared to bounce harmlessly off the ship’s hull. “Huzza! Her sides are made of iron!” the Sailor purportedly shouted—thus the ship earned the nickname Old Ironsides. In 1960, Constitution was named a National Historic Landmark by the Department of the Interior due to its extraordinary history. Constitution was designated America’s Ship of State in 2009.

Today, the Sailors of Constitution, in partnership with NHHC’s Detachment Boston, the USS Constitution Museum, and the National Park Service, work to preserve, protect, and promote Constitution for the people of the United States and the world as a living link to the Sailors and Marines of the past, present, and future. Annually, more than 500,000 people walk across Constitution’s decks.