Welcome to Navy History Matters—our biweekly compilation of articles, commentaries, and blogs related to history and heritage. Every other week, we’ll gather the top-interest items from a variety of media and social media sources that link to related content at NHHC’s website, your authoritative source for Navy history.

Compiled by Brent A. Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command Communication and Outreach Division

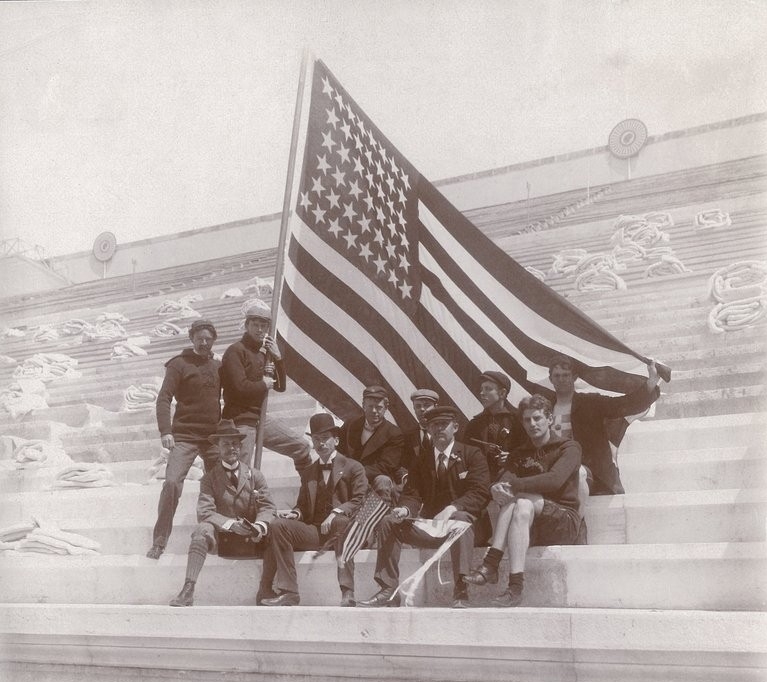

USS San Francisco at 1896 Olympics in Athens

In April 1896, 241 athletes from 14 countries competed in 43 different events at the inaugural modern Olympic Games in Athens, Greece. Although it did not have an official team, the United States sent 14 athletes to compete in three different disciplines. The delegation was largely comprised of student-athletes from athletic clubs in New England—most prominently the Boston Athletic Association. Although the delegation was small, the U.S. won the most gold medals at the games—11. Greece had the most medals overall with 47. The U.S. had 20 overall.

While the games were about to commence, USS San Francisco (Cruiser No. 5) was taking a break from patrolling the eastern Mediterranean and was anchored at the Piraeus port of Athens to allow Sailors to attend the games. Assigned to the U.S. Navy’s European Squadron in 1895, it served as the squadron’s flagship. Throughout the games, U.S. Navy Sailors cheered for the American athletes from the stands at the Panathenaic Stadium in Athens. Their presence was noted at the time by the French founder of the games, Pierre de Courbetin.

During the games, the American delegation dominated in track and field and the American Sailors made themselves heard throughout the events. John B. Connelly, who took home a gold medal in the triple jump, known then as the “hop, skip, jump,” recalled the Sailors standing at attention at the first raising of the American flag at the games in honor of his victory. “Most of the crew of the USS San Francisco were massed in the stadium bowl. Like one man they arose and stood at attention. The 80,000 spectators in the seats were rising.… The thought next came to me that our National Hymn was for my winning my event.… I went floating, not walking, floating across the stadium arena on waves that sounded like a million voices and two million hands cheering and applauding.”

The Sailors also cheered loudly for Robert Garrett, who took home gold in the discus throw and shotput. In celebration of the stellar performances of the American athletes, Rear Adm. Thomas O. Selfridge, commander of the European Squadron at the time, hosted them on board San Francisco. Selfridge later described the second day of the games in his memoirs, writing that the “Princeton athletes” performed well, “so much so that some officers from the San Francisco gave them a ‘roaring blowout’ at Piraeus to celebrate the American victory.” For more, read the article by Communication and Outreach Division’s Kati Engel in The Sextant, NHHC’s blog.

Allied Invasion of Southern France—80 Years Ago

After weeks of naval and air force bombardment, Operation Dragoon, the Allied invasion of southern France, began on Aug. 15, 1944. U.S. Eighth Fleet, commanded by Vice Adm. Henry K. Hewitt, and the Royal Navy’s Mediterranean Fleet provided the amphibious lift, bombardment/fire support, mine warfare, naval air support, and special operations forces (designated as the Western Task Force). By the time the invasion kicked off, the Germans were already demoralized and disorganized by weeks of bombardment, and except for one strongpoint that was eventually neutralized by a B-24 Liberator air strike, put up little resistance. By the evening of Aug. 17, the surviving German forces were in full retreat up the Rhone Valley, continually harassed by French resistance fighters. German air attacks on the landing forces were mostly ineffective, although an air-launched Henschel Hs-293 guided bomb sank LST-282 on the opening day of the operation. On Aug. 19, U.S. Navy F6F Hellcats and Royal Navy Seafires, on an armed reconnaissance mission, shot down five enemy bombers near Toulouse, to the west of the Allied landing areas.

Similarly, the response by already fragile German naval forces in the Mediterranean was negligible. A German torpedo boat flotilla based at Genoa, which could have sortied against the Western Task Force, remained in port and out of the fight. However, two German patrol vessels that engaged the Allies were sunk by USS Somers (DD-381) on Aug. 15 off the island of Port-Cros. On Aug. 17, to the northeast of the landing area off La Ciotat, USS Endicott (DD-495), PT boats, and gunboats of the U.S. Navy and British special operations forces were staging diversion operations when they were attacked by a German corvette and a patrol vessel. Although the Germans concentrated their fire on the outgunned Endicott, the ship, commanded by Medal of Honor recipient Lt. Cmdr. John D. Bulkeley, emerged victorious.

Following consolidation of the beachhead, French forces headed southwest to capture Toulon and Marseille. In Toulon, they encountered heavy German resistance, but it was overcome by Aug. 26. In Marseille, German forces were harried by the French resistance, which undercut the enemy’s command and control operations. By Aug. 29, the city was in Allied hands. Western Task Force ships provided gunfire support, targeting the old, but very solid, port fortifications. In both cities, the Germans were able to destroy or mine portions of the port facilities. At Marseille, U.S. Marine detachments from USS Augusta (CL-31) and USS Philadelphia (CL-41) accepted the surrender of the German units defending the Frioul islands outside of the city’s harbor.

Operation Dragoon (originally codenamed Anvil) had first been discussed at the Allied conference in Tehran in December 1943. The conference was the first time President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin met in person. At the conference, the three leaders and their staffs debated the operational timetable for 1944. All approved of Operation Overlord, the invasion of Normandy. Stalin also promised a summer offensive on the Eastern Front (Operation Bagration) and Churchill wanted to advance in the Mediterranean, preferably the Balkans. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, with Roosevelt’s backing, pushed for the invasion of southern France. Churchill was doubtful and Stalin supported the operation, but the three leaders agreed the best way to support Overlord was by amphibious landings on France’s Mediterranean coast. However, the consensus surrounding Anvil quickly vanished. Churchill argued that the invading force would get bogged down on the beach and due to the emergent need to supply the beachhead at Anzio, Anvil was dropped. Still, the American general in charge of planning for Anvil, Army Gen. Jacob Devers, continued to prepare despite the cancellation of the operation. However, when the landings on Normandy were deemed a success, the Allies had enough shipping capacity to undertake another amphibious operation and the plan for Anvil was nearly complete. It called for the American and French armies to land just east of Marseille and Toulon and capture them. The two important port cities would increase Allied supply capacity on the French mainland. Although Churchill still opposed the operation, the Americans prevailed and the operation was a go. It was renamed Dragoon on Aug. 1 for security reasons.

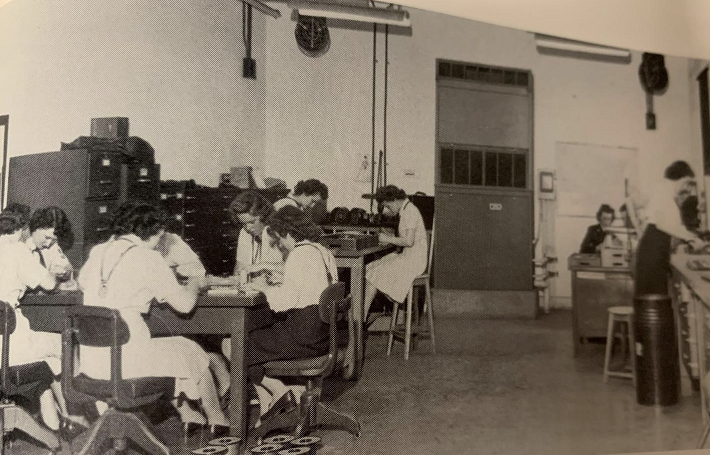

WAVES on Top Secret Duty in America’s Heartland

In 1943, the Navy began sending groups of Women’s Reserve (WAVES) by train from Washington, DC, to Dayton, Ohio, to work on a top secret project. Due to the highly secretive nature of the assignment, the WAVES were not told where they were going or what they would be doing, only that they were headed “west.” Some thought they were going to California and were surprised to arrive in Dayton several hours later. From Dayton’s Union Station, they were transported by bus to a hillside reserve dotted with cabins and maple trees in the hills a few miles outside of town. They were issued linens and pillows and directed to stow their personal items in the cabins, which would become their home for the next year or so. This 30-acre reserve, called Sugar Camp, was owned by the National Cash Register (NCR) Company.

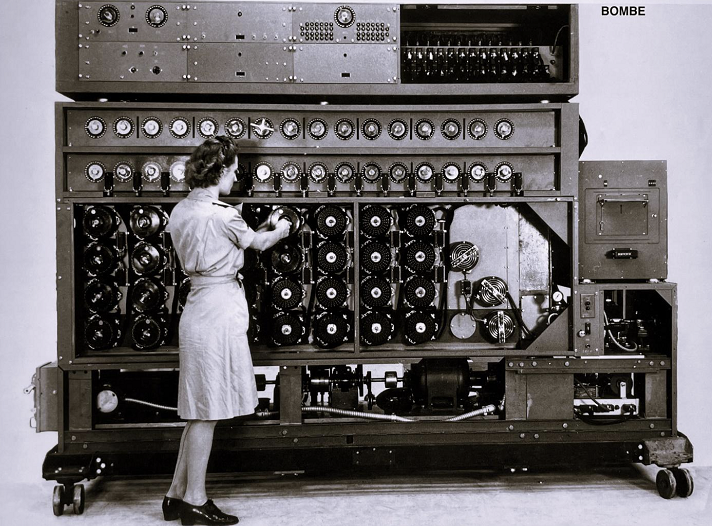

What the WAVES didn’t learn until years later is that they were there to help build the U.S. Navy’s N-530 Cryptanalytic Bombe, a 5,000-pound electromechanical machine designed to help Navy codebreakers crack the German navy’s Enigma cipher (codenamed Shark by the Allies), which utilized an encryption machine that combined the settings of four rotors and a plug board to encode messages. To decipher an Enigma message, a recipient needed an Enigma machine (or replica) and knowledge of the original settings and rotor starting positions to decipher the message. The Bombe searched all the Enigma rotor settings that allowed the cipher to match the assumed plain text and discarded those that were incorrect.

Since the British already had a Bombe machine and Enigma decryption materials, they had taken the lead on Enigma codebreaking efforts and had been successfully decrypting the German navy’s three-rotor Enigma communications since June 1941. This gave them access to German signals intelligence (which they called Ultra for “Ultra Top Secret”). Ultra intelligence had been vital to the Allies in the Battle of the Atlantic because it provided them with knowledge of U-boat locations. The British lost access to Ultra in February 1942, when the German navy switched to the four-rotor Enigma cipher. The British Bombe machine could not compute rapidly enough to attack this cipher.

In the spring of 1943, a team of contracted Navy engineers had just finished two prototype Bombe machines when the first WAVES arrived. Just out of boot camp, the WAVES marched to work at the NCR campus to maintain discipline and esprit de corps. They’d already passed their background checks prior to leaving the Naval Communication Annex in Washington, DC, and had attended security briefings, in which they were ordered not talk to anyone about the project. If asked by Dayton townspeople what they were working on, they were told to say they were learning how to use special accounting machines.

The WAVES worked at the Naval Computing Machine Laboratory on the NCR campus, where they wired and soldered parts for the Bombe machine. Soldering had not yet been automated, so it had to be done by hand. Following wiring diagrams, the women wrapped wires around prongs and soldered the tip of each wire to the contact point on a commutator wheel. They wired tens of thousands of rotors for the initial Bombe machines and additional rotors for replacement wheels. Those that were not able to master the intricate wiring of the commutator wheels assembled wire harnesses for the Bombe machine’s circuitry.

For more on this little-known topic, read the article by Communication and Outreach Division’s Wendy Arevalo in The Sextant.

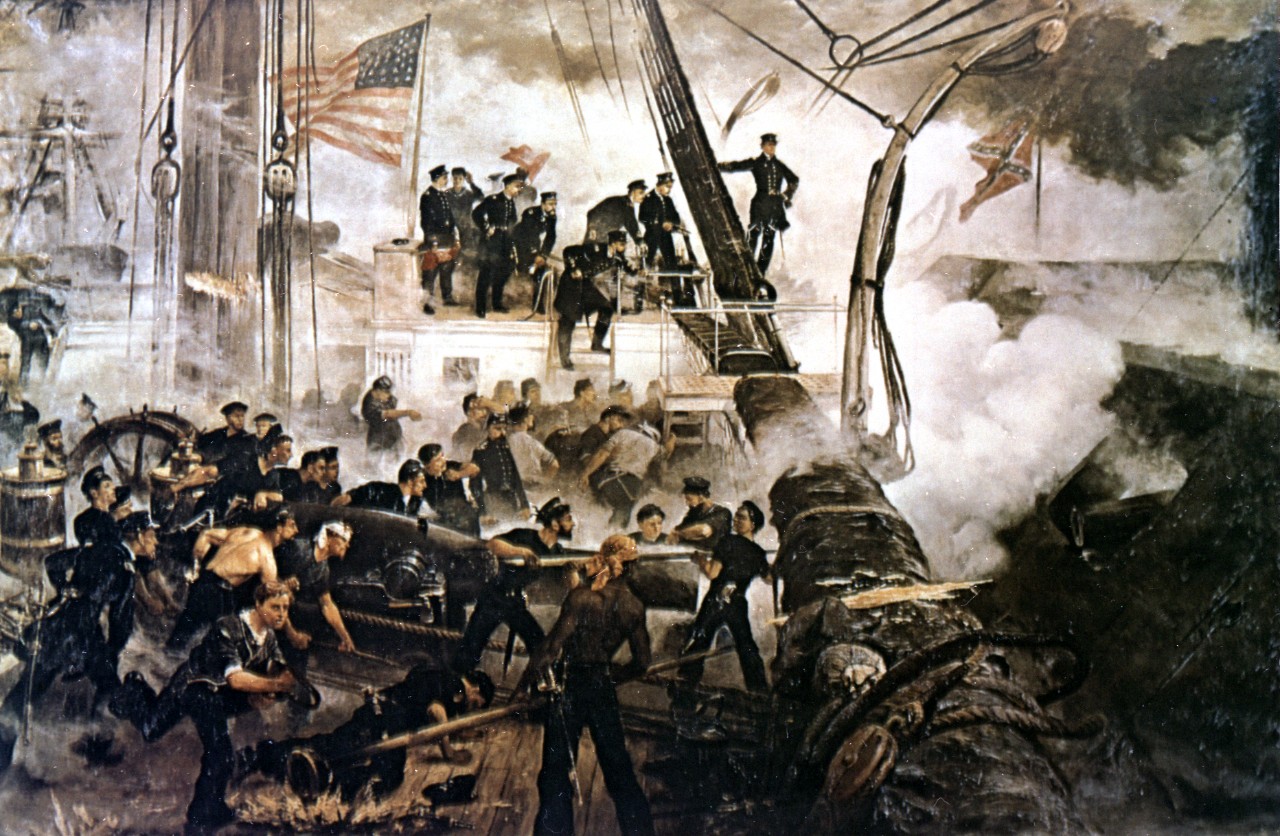

Today in Naval History—Battle of Mobile Bay

After months of shifting priorities for Union Army and Navy forces during the American Civil War, 14 wooden vessels and four ironclads of the U.S. Navy waited for the signal to steam past the heavily fortified Fort Morgan into Mobile Bay, Alabama. Before dawn in early August 1864, all 18 ships were ordered to proceed. The ironclads—Tecumseh, Manhattan, Chickasaw, and Winnebago—engaged the Confederate fort first, staying to the east of the column of wooden vessels. The second column of wooden vessels ran alongside and slightly behind the column of ironclads. As Rear Adm. David G. Farragut’s fleet approached, Confederate Adm. Franklin Buchanan watched from aboard his ironclad flagship Tennessee. His small squadron of wooden gunboats—Gaines, Morgan, and Selma—waited nearby. With a line of “torpedoes”—actually rudimentary remotely detonated sea mines—forcing the Union ships under the guns of Fort Morgan, Buchanan had no reason to take the offensive yet. Passing a buoy that marked the end of the Confederate minefield, Tecumseh hit a torpedo, which blew a hole in its hull and quickly sank the ironclad. Watching the ironclad sink, and with the Confederate ironclad ram Tennessee in waiting, Capt. James Alden of Brooklyn hesitated at the head of the second column, stopping any further movement through the narrow channel under the guns of Fort Morgan. Frustrated by Alden’s apprehension, Farragut ordered Capt. Percival Drayton to take the lead. Drayton guided Hartford around Brooklyn, heedless of the submerged torpedoes, and fired a broadside at Tennessee as the ship passed through the minefield without incident. Cmdr. James D. Johnston, of Tennessee, attempted without success to ram the leading Union vessels as they passed through the minefield, but his ironclad proved too slow to outmaneuver them.

About two hours into the Battle of Mobile Bay, all but one of Farragut’s fleet had passed the fort. Preparing to engage the enemy squadron, the second column broke apart as the senior officer of each pair of vessels cast off their lines. Farragut ordered the captain of Metacomet to lead the pursuit of Buchanan’s wooden gunboats. While engaged with Metacomet, CSS Selma became a target of another Union steamer—Port Royal. Outnumbered and outgunned, the captain of Selma surrendered the ship. Under fire, the crew of CSS Gaines was forced to beach their damaged vessel after the ship started taking on water. Morgan remained afloat, running for the cover of the fort. With his squadron scattered, Buchanan had only Tennessee left under his command. He was determined to try to sink a Union ship before the battle ended. As Tennessee slowly approached, Farragut ordered his ironclads and larger wooden ships to run down the Confederate ram. Two of the faster wooden ships, Monongahela and Lackawanna, reached the enemy first. Neither the full impact of the sloops-of-war striking the sides of the ironclad nor their cannonballs did any significant damage to its heavy armor. Farragut crashed Hartford into the ironclad, bringing the number of collisions to three. In this one-sided engagement, there was more damage to Farragut’s fleet than to the ironclad. The Union monitors arrived next, unleashing fire on Buchanan’s flagship. Surrounded by the enemy fleet, Tennessee appeared to have suffered no damage, although it ceased returning fire. As Hartford was preparing to strike again, Tennessee raised the white flag. Johnston subsequently surrendered his sword. Buchanan had been injured in the leg during the battle, so Johnston surrendered on his behalf. As a prisoner of war, Buchanan was sent to Pensacola for treatment.

Despite Buchanan’s surrender, the battle between ship and shore continued for another two weeks. Farragut sent the monitor Chickasaw to join the detachment—Conemaugh, Estrella, J.P. Jackson, Narcissus, and Stockdale—already engaged at Fort Powell. With Chickasaw firing into the rear of the fort and the others firing from the Mississippi Sound, it was not long before the commander of the garrison asked for advice from his superiors. Given the choice to stand or to retreat, Confederate Army Lt. Col. James M. Williams left with his garrison during the night. Army Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger’s forces had already taken two other Confederate-held Mobile Bay sites—Dauphin Island and Fort Gaines. With the combined firepower of Granger’s artillery and Farragut’s gunboats, Fort Powell surrendered on Aug. 8. All Union forces in Mobile Bay converged on Fort Morgan, the last remaining Confederate-held area in Mobile Bay. Farragut and Granger demanded an unconditional surrender, but its commander refused while he had any means to defend the fort. Seeking to demoralize the enemy, Farragut prepared the captured ram Tennessee to join the monitors firing upon the fort. He continued shelling Fort Morgan for the next two weeks until another white flag was raised. On Aug. 23, all three forts guarding Mobile Bay were under the control of U.S. forces.

After the Battle of Mobile Bay, the city of Mobile lay in wait. Although the city had no military significance, the occupation of Mobile, some argued, could help the campaign against Atlanta. However, Farragut insisted that occupation of the city would be more trouble than it was worth given the number of troops that would be required. The city of Mobile remained under Confederate control until the South surrendered to Union forces in April 1865.