Welcome to Navy History Matters—our biweekly compilation of articles, commentaries, and blogs related to history and heritage. Every other week, we’ll gather the top-interest items from a variety of media and social media sources that link to related content at NHHC’s website, your authoritative source for Navy history.

Compiled by Brent A. Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command Communication and Outreach Division

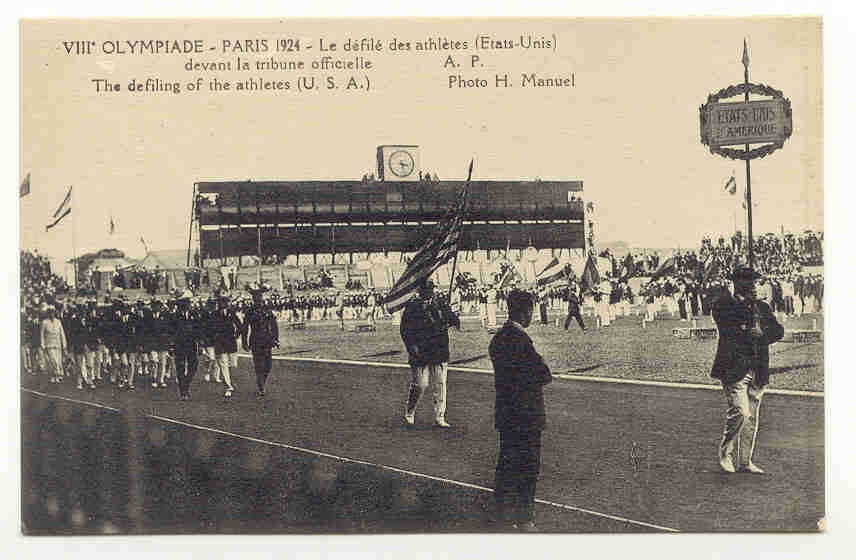

U.S. Navy at the 1924 Olympic Games in Paris

A century ago, with the endorsement of Secretary of the Navy Edwin Denby, Rear Adm. Thomas Washington, chief of the Bureau of Navigation, encouraged all service members in the U.S. Navy and the Marine Corps to participate in the 1924 Olympic Games in Paris. Anyone who wished to train was considered on temporary duty in connection with the Olympic tryouts, which started in April 1924. Those competing for the Olympic Rifle Team gathered at Quantico, Virginia, for the national trials in May 1924. Among those selected to compete on the official team was U.S. Navy Cmdr. Carl T. Osburn. This would be his third consecutive Olympiad, building on the 10 medals he had won previously during the 1912 and 1920 games.

The opening ceremony for the 1924 Olympics was scheduled for July 5, but competition actually started earlier for some of the athletes. The U.S. Rifle Team had to depart for Europe early, because their events were scheduled for early June. Within two weeks of being selected, the team’s members departed from New York aboard SS President Harding, headed for France. Tryouts for other sports continued in the United States through June.

Some of the Navy personnel who had competed in the 1920 games had hopes of taking part again, but the competition with athletes from universities and athletic clubs across the country was fierce. The U.S. Navy not only planned to send a crew from the Naval Academy to the Olympic rowing trials, but also organized the champions of the 1920 team—all graduates of the Naval Academy—to form an “officers’ team.” Both of the crews from the academy, the midshipmen and the graduates, prepared side by side in Annapolis, Maryland, for more than two months before the national competition in June. Both teams were favored at Olympic tryouts, but the crews from Yale University defeated both of them. After they failed to make the U.S. Olympic Team, the officers were detached and returned to their respective commands.

Naval Academy boxing coach Spike Webb was chosen to take the national team to the Olympic Games. Although he brought a large contingent of midshipmen and ensigns to tryouts, the committee picked the Navy athletes to serve as alternates after they lost a few close matches. In fencing, a group of midshipmen were selected to represent their country, including Ensigns Georg Calnan, Edwin Fullinwider, Alvin Becker, and Thomas Jeter. It was the second Olympic Games for both Calnan and Fullinwider, who had both competed in 1920.

In the summer of 1924, the U.S. Navy was also well represented among the crowds headed to Paris to watch the athletes participate in the Olympic Games. The midshipmen of the Naval Academy did not embark on their traditional summer cruise, as they were assigned to the ships of Battleship Division 2, Scouting Fleet: USS Wyoming (BB-32), USS New York (BB-34), USS Texas (BB-35), and USS Arkansas (BB-33). They were scheduled to head to England and then to France, arriving in Brest on June 26, just in time for the opening of the games in Paris. Liberty time was generous during this cruise, although the older battleships required the midshipmen to load coal into the ships’ fuel bunkers at each port call. USS Pittsburgh (CA-4) also arrived at Cherbourg in early July 1924. Naval personnel from all of these ships were then granted shore leave to attend the games, although not all attended.

The ceremonial protocols first enacted in 1920 were repeated in 1924, including the raising of the Olympic flag and the official athletes’ oath. For the first time, all the athletes lived in an Olympic village near the stadium in Paris. Although the buildings were simple huts, they were furnished with both cots and actual mattresses, which was an improvement for the American athletes who had attended the 1920 games in Antwerp, Belgium. The organization of the 1920 Olympiad had been haphazard and underfinanced, but it had brought the games back after World War I. Now, the 1924 Olympic Games signaled a new phase in the evolution of the international competition.

Although the U.S. Navy was not represented as strongly as it had been in 1920, but the inclusion of the service’s personnel in various disciplines helped ensure the continued success of American Olympians that had begun with the 1896 inaugural games. The participation of the U.S. Rifle Team created a legacy that was unmatched for the next 48 years. Cmdr. Osburn had won his first four medals in 1912, six medals in 1920, and finally, one medal in 1924 for a total of 11 medals. The silver medal he won in 1924 made him the most decorated American competitor (NHHC has some of Osburn’s Olympic Medals in its holdings). This record was unmatched until 1972, when American swimmer Mark Spitz won his 11th medal.

For more on the 1924 Olympic Games, read the blog by Communication and Outreach Division’s Kati Engel at The Sextant. Also, read about the Navy’s participation at the 1920 Olympic Games in Antwerp, Belgium.

VJ Day

On Sept. 2, 1945, more than two weeks after accepting the Allies’ terms, Japan formally and unconditionally surrendered, marking the end of World War II. During the brief 20-minute ceremony, the instrument of surrender was signed by representatives of the Allied and Japanese governments onboard USS Missouri (BB-63) in Tokyo Bay. Japanese Foreign Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu signed on behalf of the Japanese government, and Gen. Yoshijiro Umezu signed for the Japanese armed forces. For the Allies, General of the Army Douglas MacArthur signed next, followed by senior officers from the United States, China, Britain, the Soviet Union, Australia, Canada, France, the Netherlands, and New Zealand. Fleet Adm. Chester W. Nimitz signed for the United States. Afterward, millions around the world erupted in celebration. The bloodiest conflict in human history was finally over.

Leading up to Japan’s surrender, the Japanese navy and air force were completely devastated, and with the successful campaigns on Iwo Jima and Okinawa, the Allies were just steps away from Japan’s home islands. In addition, shortages of food, fuel, and strategic materials left both the Japanese military and civilian populace in dire straits. The Imperial Japanese Navy no longer had enough fuel in their reserves to go to sea. Strict conservation of aviation fuel grounded most of Japan’s aircraft. Moreover, the Soviet Union refused to renew its neutrality pact with Japan. The defeat of Japan was a foregone conclusion.

During the previous months, as the Allies prepared for an invasion of Japan (codenamed Operation Downfall), President Harry S. Truman had asked his top advisors what they believed the cost of lives would be in the invasion. Some estimated it could be up to one million Allied and Japanese lives lost. On July 16, a new option became available when the United States detonated the first atomic bomb at the Trinity test site at Alamogordo, New Mexico. Ten days later, the Allies issued the Potsdam Declaration, demanding the unconditional surrender of all Japanese armed forces. Terms included complete disarmament, occupation of certain areas, and the creation of a “responsible government.” It also promised that Japan would not be enslaved as a race or destroyed as a nation. The declaration ended by warning of “prompt and utter destruction” if Japan failed to surrender unconditionally. In late July, Japanese Prime Minister Kantaro Suzuki responded by telling the press that the Japanese government was “paying no attention” to the Allied ultimatum. At that point, President Truman made the tough decision and ordered an atomic bomb to be dropped on Japan. On Aug. 6, U.S. B-29 bomber Enola Gay dropped “Little Boy” on Hiroshima, killing an estimated 90,000 to 120,000 Japanese. To further complicate matters for Japan, the Soviet Union declared war on that nation the next day.

After the devastation of the Hiroshima attack, a faction in Japan’s supreme war council favored the acceptance of the Allies’ terms. However, believing the United States only had one atomic bomb, the majority of the council resisted an unconditional surrender. On Aug. 9, a second atomic bomb, “Fat Man,” was dropped on the large port city of Nagasaki, killing an estimated 129,000 to 226,000 Japanese. In the aftermath, Emperor Hirohito called an imperial conference of all high-level advisers to discuss an unconditional surrender. Although there were disagreements, on Aug. 10, Emperor Hirohito relayed a message to the United States that Japan would surrender unconditionally. On Aug. 14, Hirohito’s surrender announcement to the Japanese nation was recorded. Despite an attempted last-minute coup by radical militarists, the message was broadcasted the next day. Of note, Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, and the United Kingdom celebrate V-J Day on Aug. 15—the day Emperor Hirohito’s surrender message was broadcasted to the Japanese people on Radio Tokyo.

Last Navy Airship Flight—End of an Era

On Aug. 31, 1962, the last flight of a Navy airship was made at Naval Air Station Lakehurst, New Jersey. The Secretary of the Navy had announced about a year earlier that he was going to terminate the Navy’s long-troubled lighter-than-air program. The Navy initially launched the program when it awarded its first contract for an airship, DN-1, to the Connecticut Aircraft Company in June 1915. During construction of the non-rigid airship, the Navy authorized the building of a hangar to house the new airship, which was completed in early 1916. DN-1 arrived in Pensacola, Florida, in December 1916, but was not ready for flight until April 1917. Once test flights began, multiple problems were revealed. The airship was severely damaged during one of the test flights and it was never repaired.

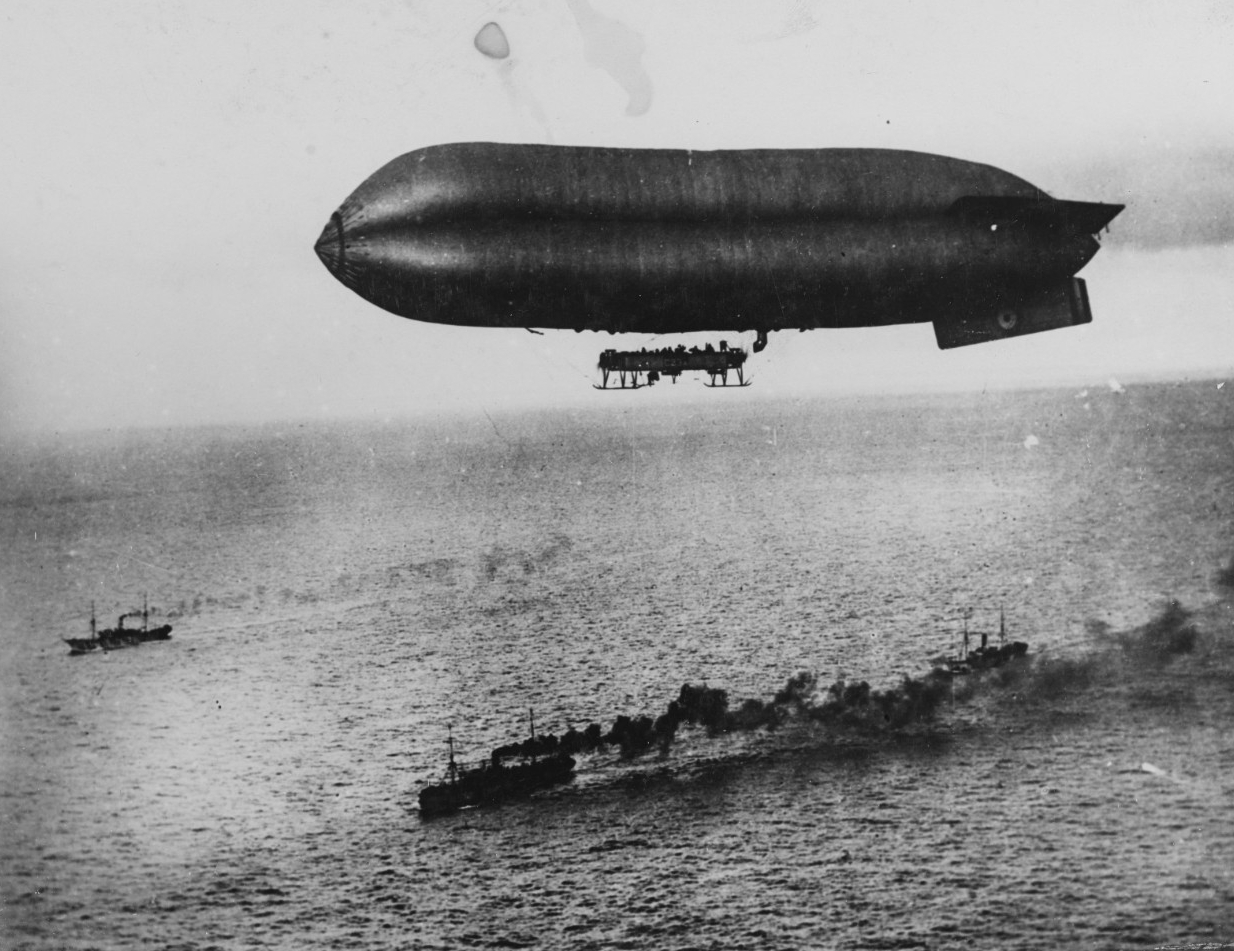

Even before DN-1 was built, studies were ongoing at the Bureau of Construction and Repair for a future class of dirigibles. In April 1916, the General Board endorsed the development of zeppelins and other mobile lighter-than-air craft. At Akron, Ohio, the Navy’s program tested non-rigid airships, free balloons, and kite balloons. During testing, the balloons were found to be an easy target for enemy aircraft and restricted maneuverability when moored to a ship. During World War I, airships and kite balloons were used in conjunction with seaplanes and flying boats to help protect shipping. They were also used to detect submarines and warn vessels of mines. Most of the airship patrols were carried out off the U.S. East Coast and in European waters, where they were deemed successful because they were a deterrent to German submarines.

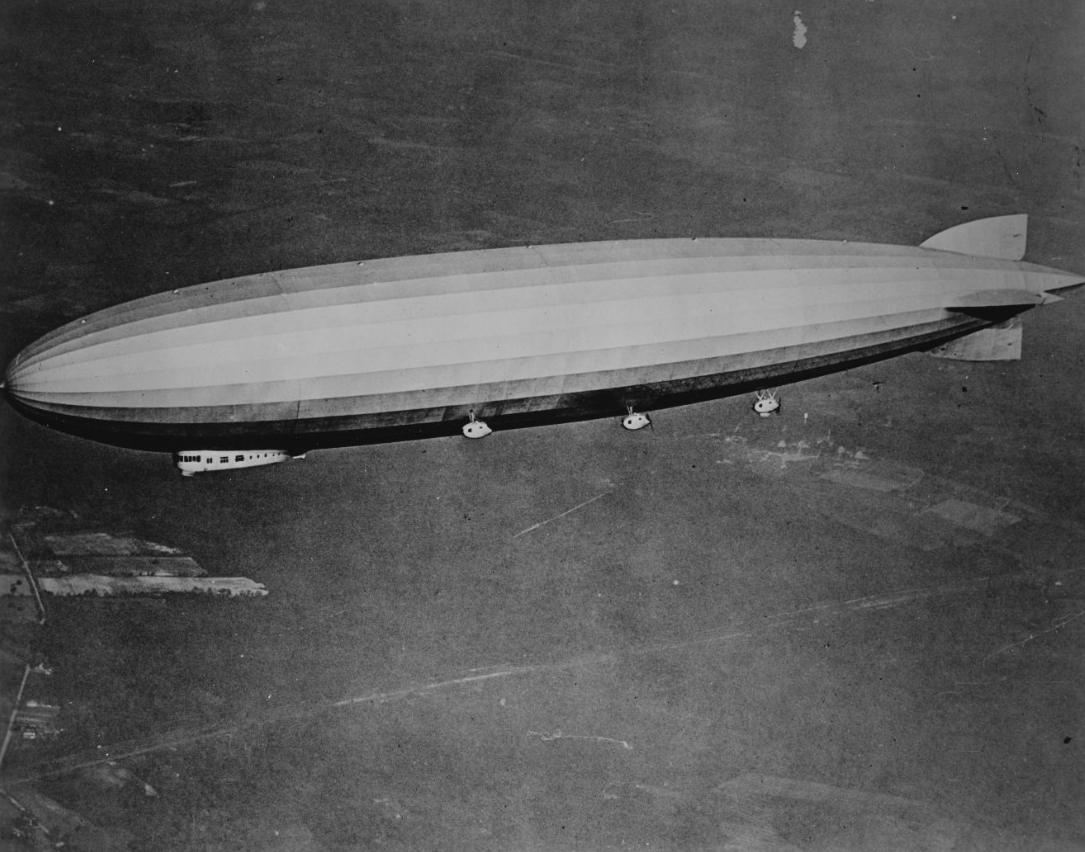

After World War I, the development of non-rigid airships became more advanced as new capabilities were developed. The Navy contracted Goodyear to build airships and hangers were built to accommodate them. The airship Shenandoah (ZR-1) was the first rigid airship to be inflated with helium and the first to fly across the United States. On Sept. 3 1925, while flying over Ohio, Shenandoah ran into a severe storm that broke the airship in two, killing about half the crew. The most successful airship of the time was Los Angeles (ZR-3). The airship had been built by Germany and was given to the United States as compensation for two U.S. airships that were lost during the “Great War.” Los Angeles was in operation more than seven years and made more than 330 flights.

Probably the most prolific period in the Navy’s construction of rigid airships was during the era of Akron (ZRS-4) and Macon (ZRS-5). They were viewed as an improvement on the Shenandoah design, having the ability to house and carry scouting aircraft, although they ended up being the first and last flying carriers. Akron was lost in 1933 off the coast of New Jersey during a storm that killed 73 crewmembers and Macon was lost off the Santa Barbara Islands, California, killing 83.

During World War II, there were five different airship classes/types in the Navy’s inventory. Airship operations and their expansion were unprecedented. The airship fleet conducted operations in the Pacific, Mediterranean, and in the northern and southern Atlantic. When the war was over and the military drew down, the Navy still retained two squadrons that conducted mostly training, search and rescue, observation, and photography missions until the program was cancelled and an era in naval history ended.

Today in Naval History—U.S. Marines Deploy to Lebanon

On Aug. 20, 1982, a multinational peacekeeping force from the United States, France, Italy, and Great Britain deployed to Lebanon in an effort to stabilize the country and stop the fighting among Syria, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), and Israel. The contingency—including the first 800 U.S. Marines from the 32nd Marine Amphibious Unit (MAU)—agreed to oversee the PLO’s evacuation and by Sept. 10, through high-level diplomacy, the PLO left the port of Beirut. The Marines departed as well, considering the mission complete. Just four days later, the president-elect of Lebanon, Bashir Gemayel, was assassinated. In response, elements of Lebanese forces avenged his death by massacring more than 1,000 unarmed Palestinians. Lebanon was once again in chaos. In response, the multinational force was ordered back to Beirut, and by Sept. 29, elements of 32nd MAU had landed for a second time in the war-torn country.

Initially, the multinational force’s mission was to establish a presence in Beirut to provide the stability necessary for the Lebanese government to regain control of the capital city and to train the Lebanese armed forces to become effective. Although the Marines were deemed “peacekeepers,” their presence was anything but peaceful. Hampered by a multitude of unexploded ordnance, sniper fire, and terrorist attacks, the presence of the Marines in Beirut turned to tragedy when on the morning of Oct. 23, 1983, two truck bombs struck separate buildings housing U.S. Marines and French forces, killing nearly 300 American and French service members. It was the single deadliest day in U.S. Marine Corps history since the World War II Battle of Iwo Jima.

On Dec. 3, an F-14 reconnaissance flight from USS John F. Kennedy (CVA-67) was fired on from Syrian-controlled territory. The following day, a strike force of 28 aircraft was launched from USS Independence (CVA-62) and John F. Kennedy against Syrian positions in the Bekaa Valley. During the engagement, an A-7 Corsair and an A-6 Intruder were shot down by intense ground fire. The A-7 pilot successfully ditched offshore. However, A-6 pilot Lt. Mark Lange was killed in action and his bombardier-navigator, Lt. Robert Goodman, was taken prisoner. Goodman was released on Jan. 3, 1984, after 30 days of captivity. However, after the attack was carried out, aerial photos revealed the strike was only marginally successful. In the days following, reconnaissance flights were conducted without incident.

In the first two months of 1984, the situation in the country had severely deteriorated. The Lebanese army was plagued by defections and desertions, and consistent heavy fighting had further reduced its capabilities. By Feb. 7, Beirut had been lost to factional militias. At this point, the Marine presence could no longer contribute to the hoped-for national reconciliation. Accordingly, President Ronald Reagan ordered the Marines to withdraw to Sixth Fleet ships offshore. By Feb. 23, the Marines began movement to reembark, ending 17 months of continuous operations in the country.